|

1. Judson Church is Ringing in Harlem (Made-to-Measure) / Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at the Judson Church (M2M), Trajal Harrell + Thibault Lac + Ondrej Vidlar (Festival TransAmériques) American choreographer Trajal Harrell’s work has always been impressive if only for its sheer ambition (his Twenty Looks series currently comprises half a dozen shows), but Judson Church is Ringing in Harlem (Made-to-Measure) is his masterpiece. In the most primal way, he proves that art isn’t a caprice but that it is a matter of survival. Harrell and dancers Thibault Lac and Ondrej Vidlar manifest this need by embodying it to the fullest. The most essential show of this or any other year. 2. ENTRE & La Loba (Danse-Cité) & INDEEP, Aurélie Pedron Locally, it was the year of Aurélie Pedron. She kept presenting her resolutely intimate solo ENTRE, a piece for one spectator at a time who – eyes covered – experiences the dance by touching the performer’s body. In the spring, she offered a quiet yet surprisingly moving 10-hour performance in which ten blindfolded youths who struggled with addiction evolved in a closed room. In the fall, she made us discover new spaces by taking over Montreal’s old institute for the deaf and mute, filling its now vacant rooms with a dozen installations that ingeniously blurred the line between performance and the visual arts. Pedron has undeniably found her voice and is on a hot streak. 3. Co.Venture, Brooklyn Touring Outfit (Wildside Festival) The most touching show I saw this year, a beautiful portrait of an intergenerational friendship and of the ways age restricts our movement and dance expands it. 4. Avant les gens mouraient (excerpt), Arthur Harel & (LA)HORDE (Marine Brutti, Jonathan Debrouwer, Céline Signoret) (Festival TransAmériques) wants&needs danse’s The Total Space Party allowed the students of L’École de danse contemporaine to revisit Avant les gens mouraient. It made me regret I hadn’t included it in my best of 2014 list, so I’m making up for it here. Maybe it gained in power by being performed in the middle of a crowd instead of on a stage. Either way, this exploration of Mainstream Hardcore remains the best theatrical transposition of a communal dance I’ve had the chance to see. 5. A Tribe Called Red @ Théâtre Corona (I Love Neon, evenko & Greenland Productions) I’ve been conscious of the genocide inflicted upon the First Nations for some time, but it hit me like never before at A Tribe Called Red’s show. I realized that, as a 35 year-old Canadian, it was the first time I witnessed First Nations’ (not so) traditional dances live. This makes A Tribe Called Red’s shows all the more important. 6. Naked Ladies, Thea Fitz-James (Festival St-Ambroise Fringe) Fitz-James gave an introductory lecture on naked ladies in art history while in the nude herself. Before doing so, she took the time to look each audience member in the eye. What followed was a clever, humorous, and touching interweaving of personal and art histories that exposed how nudity is used to conceal just as much as to reveal. 7. Max-Otto Fauteux’s scenography for La très excellente et lamentable tragédie de Roméo et Juliette (Usine C)

Choreographer Catherine Gaudet and director Jérémie Niel stretched the short duo they had created for a hotel room in La 2e Porte à Gauche’s 2050 Mansfield – Rendez-vous à l’hôtel into a full-length show. What was most impressive was scenographer Max-Otto Fauteux going above and beyond by recreating the hotel room in which the piece originally took place, right down to the functioning shower. The surreal experience of sitting within these four hyper-realistic walls made the performance itself barely matter.

1 Comment

C’est un spectacle. I don’t know why anyone would expect anything else when going to Place des Arts to witness Nederlands Dans Theater passing through Montreal for the first time in over twenty years. For the occasion, we were treated to a Crystal Pite sandwich on Sol León & Paul Lightfoot bread. Sehnsucht opens and ends with a man bowing in a frog-like position at the front of the stage. In the background, a straight couple engages in a pas de deux in a cubic room. Like the needles of a clock, their legs and arms stretch out and rotate around a two-dimensional axis. Their movement is fast-paced while that of the man in the foreground is fluid but sculptural in its slowness and poses, as though time passed more slowly for those alone. The room spins vertically, so that the dancers sometimes appear to defy gravity like Fred Astaire in Royal Wedding, sitting on a chair that hangs from a wall, for example. The choreographers use this magical element to charm the public without pushing it to the point where it would transcend its gimmick. The room disappears and thirteen dancers come out for the middle section. They dance synchronously in a manner that is reminiscent of Ohad Naharin’s Hora: the athletic bodies of the dancer maintain the legs of ballet (pirouettes included); however, while the upper bodies in Hora could be said to fall under a post-modern aesthetic, here they are more akin to music video choreography. (The synchronicity might partially be to blame for this.) The fast pace of the choreography follows along the gaudiness of Beethoven’s Symphony Nr. 5, resulting in the kind of comic effect that the Looney Tunes capitalized on.

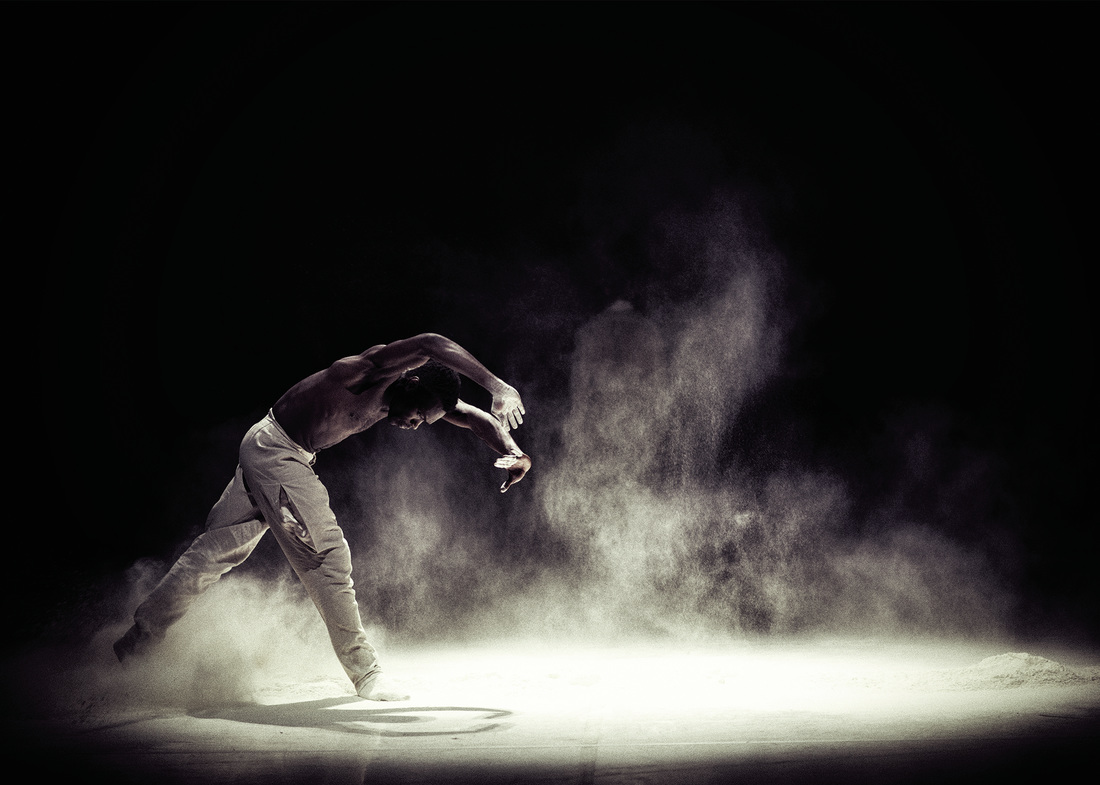

Canadian choreographer Pite offers the strongest piece of this triple bill with In the Event. Set against a grey sandy backdrop, eight dancers appear like a group on an expedition through the darkness of a foreign planet. The world around them feels potentially threatening, from their shadows moving along the walls of a cave to the rumbling on the soundtrack and the lightning that shatters the background. However, the dancers are in it together, cooperating as a group, sometimes literally forming a human chain with their limbs. The movement is elastic, round, and refreshingly ungendered. The dancers slide against the floor, sometimes even float above it. A solo provides the piece with a dramatic ending as a man’s hands frantically search the floor and reach for his chest and throat as if he were choking. For Pite, being alone looks like being lost. León & Lightfoot fare better with Stop-Motion, a piece for seven dancers that is gothic-looking with its black background, white and beige pants, white walls, floor and powder, and black and white video projection. The dance is better served by Max Richter’s moody modern classical music. In solos and duos, the agility of the dancers is used to evoke emotion rather than being an end in and of itself like in Sehnsucht. However, the choreographers once again go for synchronicity for the group section; rather than intensifying the effect, it comes across as lazy and dilutes it. As the piece ends, some curtains are lowered while others after are lifted, and the lighting grid also comes down. There is the feeling that León & Lightfoot are doing this just because they can. With this triple bill, they show that they have the dancers and the means to make great art, but they fail to prove that they have the will. November 1-5 at 8pm www.dansedanse.ca 514.842.2112 / 1.866.842.2112 Tickets: 41.50-70$ Peter Trosztmer is both dancer and conductor in AQUA KHORIA, his collaboration with musician-digital artist Zack Zettle. Set within the dome of the SAT, Trosztmer evolves against a 360-degree animated projection that reacts to light and movement. In the middle of the floor: a small circular pond.

As we enter the room, we are surrounded by buoys, gently rocking their bells in the middle of the night. After the doors close behind the last spectator, Trosztmer whips the waters into a storm with his rain dance, looking like Mickey Mouse moving brooms about with his magic. The tumultuous waters swallow us into the calmness of its depth, pushes us back out, and ultimately pulls us back in. Follows an exploration of this underwater world, like an animated documentary without voice-over narration where experience is privileged over knowledge. A drop of water falls into the pond. (How nice it would have been had it been mic’ed.) As the pond is lit, we perceive its reflection as light play on the dome, a sky made of water. Sometimes I find myself believing that through art we’re looking to capture something of nature that we’ve lost: the chaos and the beauty. It would explain why there’s so much art in the city and so little in the country. Trosztmer approaches the water on all fours. When he finally dips his paws in, he stands but remains hunched over. We are simultaneously witnessing evolution and regression as a human being goes back to the water that we came from. The drop of water falls on him before turning into a stream in a quasi-Flashdance moment, as Trosztmer is now down to his underwear. We reach a cave of moving shadows as Trosztmer walks around the space holding a candle, and travel through a tunnel without taking a single step. Trosztmer then goes back to playing conductor with his movement, which espouses the shape of the dome: height and circumference, what we are guessing are the two main ways of controlling the sound. The music is provided by harp-like-sounding notes from a synthesizer backed by a chill beat, which ends up sounding like Muzak for a spa. We then find ourselves in what looks like lava inside a whale (or at least its bones), like Jonah. Soon, the whale is caught in a whirlpool and we are spat back out to the surface of the water, now calm again, as seagulls fly overhead. There is something of IMAX in the simplistic narrative followed here: exposition (calm waters), conflict (storm), journey (cave), climax (whirlpool), resolution (calm waters). Of course, we’re more interested in the 360-degree projection than we are in the dance. Who could possibly compete with technology? There could be a ten-inch screen broadcasting hockey behind a dancer and we’d find ourselves watching the game. Some transitions could have been smoother as the music, projection and performance keep changing at the same time, but ultimately AQUA KHORIA does play like an IMAX movie: pleasant while it lasts but otherwise unmemorable. October 11-21 www.tangente.qc.ca / www.danse-cite.org 514.844.2033 Tickets: 25$ A month ago, I wrote that I go see dance because I love when people shut the fuck up. Yet last night I was ready to completely backtrack on this statement. It just goes to show that, with art, there is never any definite set of criteria that one can judge a work by, that art is chemistry that produces as many reactions as there are elements and audience members.

The occasion was Belgium-based American choreographer Meg Stuart’s unmissable return to Usine C with her solo Hunter. Her father was a community theatre director, she will tell us. As a result, she witnessed a lot of bad acting as a child, so she swore she’d never speak onstage. And for the first hour of this 90-minute show, she doesn’t. Treating her body as an archive of dance and memories, she moves in the style that has made her a contemporary dance icon. The collage aspect of the work is underlined incessantly, from the actual collage Stuart is making sitting at a table (and projected onto a screen at the back of the stage) at the beginning of the show to the sound collage by Vincent Malstaf and the video collage by Chris Kondek. I hear you loud and clear. It might be this aspect that most deters from the work. Like the soundtrack that moves through sound clips as though someone were switching through radio dials and never settling on any one channel, Stuart never sticks with anything for long, making us feel like we’re looking at a dancer improvising in the studio as she maintains a steady pace that comes across as manic. We want to tell her to calm down, to stand still for a moment. In her last show seen in Montreal, Built to Last, Stuart had touched on the ephemeral nature of dance by contextualizing it within a set that included a giant mobile of our solar system and mock-up of a T. rex skeleton. However, even though the set is also imposing in Hunter, it still replicates the blankness of the black box. In effect, it is like the table upon which Stuart does her collage: a rectangular blank surface on which beams are scattered around (like the pins used for her collage) from which rolls of fabric hang and are used as screens for the video projections. As a result, Stuart’s dance is decontextualized. What a welcomed change it is when she finally speaks. She maintains the stream of consciousness trope used throughout the show, but we do want to hear what she has to say about her life, about art, about anything. She’s Meg Stuart. She can speak onstage as much as she wants and we’ll listen. October 13-15 at 8pm www.agoradanse.com / www.usine-c.com 514.521.4493 Tickets: 38$ / Students or 30 years old and under: 30$ En 2014, la chorégraphe Aurélie Pedron crée ENTRE, performance pour un spectateur à la fois. Les yeux bandés, celui-ci découvre l’œuvre au toucher, en demeurant en contact avec la danseuse. L’année suivante, elle remporte Le prix DÉCOUVERTE de la danse de Montréal. Au début de 2016, elle poursuit avec INDEEP, une performance de dix heures où des jeunes de la rue, les yeux bandés, évoluent dans un espace clos. Cette semaine, elle récidive avec LA LOBA, un déambulatoire composé de douze performances en simultané dans l’ancien institut des sourds et muets, jadis géré par des religieuses. SYLVAIN VERSTRICHT Comment as-tu découvert l’espace du 3700 Berri? AURÉLIE PEDRON Après mille téléphones. Des personnes qui m’ont envoyé à des personnes référentes qui m’ont envoyé à des personnes référentes… C’est quelqu’un qui travaillait pour l’Arrondissement du Plateau qui m’a dit « Tu devrais essayer de contacter l’institut des sourds et muets (qui est encore de l’autre côté de la bâtisse). Leur bâtisse est vide. » J’ai appelé là-bas. Ils m’ont donné le numéro de téléphone de la personne qui travaille au Gouvernement du Québec – parce que cette bâtisse appartient maintenant au gouvernement – puis il y a un employé de la location des espaces vacants et voilà! De tous les espaces vacants de Montréal – il y en a des millions – de tous ceux que j’ai réussi à contacter, c’est le seul que j’ai réussi à visiter et à louer. VERSTRICHT Qu’est-ce que tu cherchais en particulier? PEDRON Je cherchais un espace vide et suffisamment grand pour accueillir douze performances. VERSTRICHT Quel est ton rôle dans cette nouvelle création, LA LOBA? PEDRON Chorégraphe, parce que je travaille avec des corps, mais c’est très « installation-performance » tout ce qu’on a bâti. C’est performatif aussi parce que le temps va transformer l’état des interprètes et parce que je travaille avec d’autres matériaux, que je les mets en relation. Je suis vraiment entre les arts visuels et la danse. Les interprètes ont leur grande part de création aussi parce que je les fais beaucoup travailler sur de longues, longues improvisations. Elles me donnent du matériel et je construis à partir de ce matériel et de qui elles sont comme personnes. Ça, c’est important pour moi. VERSTRICHT Comment as-tu choisi ces interprètes? PEDRON Par instinct, beaucoup. Mais en fin de compte je réalise que j’ai rassemblé un bassin de personnes qui ont le même fond, une profondeur. VERSTRICHT Y a-t-il quelque chose qui relie toutes ces installations? PEDRON Oui, mais je n’ai pas envie de donner de thématiques. Je me bats comme un beau diable, parce que je trouve qu’il y a évidemment quelque chose qui a émergé de ce travail. Tu es au cœur d’une étoile. C’est douze performances. Ce n’est pas un spectacle avec un début, un milieu, une fin. Quand les spectateurs arrivent, ça a déjà commencé. Ça peut avoir commencé il y a mille ans, on n’en sait rien. Et, quand ils partent, peut-être que ça va continuer encore mille ans. VERSTRICHT Donc c’est un déambulatoire en continu où les spectateurs sont laissés à eux-mêmes? PEDRON Oui. Ils ne sont pas guidés. Il n’y a pas de chemins. Il y a juste quelques performances qui sont pour un spectateur à la fois, alors là il faut qu’ils s’inscrivent en arrivant. Ça se déroule sur trois heures. VERSTRICHT Qu’est-ce qui était là au début? Voulais-tu travailler quelque chose en particulier? PEDRON Il y a deux choses sur lesquelles je voulais travailler : le rapport au temps et à l’espace, pour l’interprète et pour le spectateur. Le rapport au temps, je l’ai déconstruit parce qu’il n’y a pas de linéarité et que le spectateur va savoir quand c’est bon pour lui, quand il en a assez d’une performance. S’il a envie de rester trois heures avec Rachel Harris, il peut rester trois heures avec Rachel. S’il veut rester une minute par performance et s’en aller au bout d’un quart d’heure, c’est parfait aussi. Je n’aime plus du tout le spectacle sur scène. Je ne suis plus bien avec ça. On a beau essayé de se décoincer des paramètres qui font que le théâtre est dans une salle, je n’y arrive pas. Milieu, début, fin : ça ne m’intéresse pas. Faire un show entre trente minutes et une heure, peut-être une heure trente si tu es super audacieux, je me sens coincée. J’avais envie de déconstruire ça et l’espace du public. Je trouve que d’avoir une centaine, deux cents, mille, deux milles personnes assises en face de toi… Le quatrième mur, il n’est pas entre l’espace du spectateur et des performeurs. Le mur, c’est les spectateurs. Ça, on ne peut pas le déconstruire. Ça fait qu’il faut exploser les spectateurs, d’où l’idée du déambulatoire. La performance dans la pièce où nous sommes présentement, ce sera juste pour quatre spectateurs à la fois. D’autres performances, un à un. On n’est pas engagé de la même manière comme spectateur. Quand on est dans un rapport de proximité et dans l’intimité du performeur, on devient super important et on voit notre potentiel à transformer l’œuvre. VERSTRICHT Tu t’es rendue compte de ça assez vite parce que tu n’as pas fait tant de pièces que ça dans des théâtres… PEDRON La dernière pièce que j’ai faite dans un théâtre était Corps caverneux et j’ai eu une insatisfaction avec cette pièce-là. J’avais touché une matière qui était intéressante pour moi, je n’étais pas nulle part, mais il manquait quelque chose. Et cette pièce-là, je l’ai écartée, je l’ai morcelée et j’en ai fait un parcours déambulatoire pour un spectateur à la fois dans un sous-sol au Festival de théâtre de rue de Lachine, puis là c’était magnifique. La pièce se tenait. C’était complet. C’est à partir de ce moment-là que j’ai réalisé qu’il faut que je déconstruise les formes. Je ne me sens pas à l’aise dans la forme traditionnelle. Je ne suis pas à mon meilleur et j’ai moins de plaisir à travailler comme ça. À partir de ce moment-là, j’ai fait ENTRE et j’ai fait d’autres performances avec des jeunes. J’ai beaucoup travaillé avec des jeunes marginaux ces dernières années et j’ai expérimenté un paquet d’affaires qui étaient vraiment satisfaisantes pour moi comme créatrice. INDEEP, qu’on a fait l’année dernière, était une performance de dix heures dans un lieu clos où les dix jeunes étaient à l’aveugle. C’était puissant. VERSTRICHT Il y a deux qualités principales qui m’apparaissent dans ton travail. Une qui y est de plus en plus, c’est la relation. Dans ENTRE, avec le spectateur, c’était flagrant. Quand tu parles d’intimité dans LA LOBA, est-ce que c’est une de tes préoccupations? PEDRON La qualité relationnelle, oui. Qu’on se dévoile mutuellement. Que l’interprète devienne interprète parce qu’il y a un spectateur et que le spectateur devienne spectateur parce qu’il y a un interprète. Ça, on le perd quand le public est une masse, parce que tu deviens anonyme. Tu es dans ton siège avec tous les autres spectateurs et tu attends que ça vienne jusqu’à toi. Tu deviens plus consommateur. Moi, je veux inverser les rôles. Je veux que tu ailles vers ce qui se passe. Parce que le spectateur est super important pour moi. C’est lui qui finit l’œuvre parce qu’il va s’en faire une image. Je ne veux rien lui imposer. J’aime qu’il aille puiser dans ses propres mémoires ce que ça évoque. VERSTRICHT L’autre qualité de ton travail qui reste d’une pièce à l’autre même si je les trouve très différentes, c’est quelque chose de politique. C’était peut-être plus évident dans tes premières pièces, mais je trouve que c’est encore présent dans INDEEP et même dans ENTRE, même si c’est plus subtil. Est-ce encore présent dans LA LOBA? PEDRON Ça ne se veut pas politique mais ce l’est. Je ne suis pas dans une revendication politique. ENTRE, c’est complètement politique, mais je m’en suis aperçue après. C’est anticapitaliste au boutte. C’est pour un spectateur à la fois. J’essaie de vendre ça aux diffuseurs : « –Ce n’est pas la quantité qui compte; c’est la qualité! » (rires) « –Oui, mais nous, on a des comptes à rendre au gouvernement. –Mais nous, on fait de l’art, pas de la politique! » (rires) Mais c’est non-rentable. Tu vas avoir douze spectateurs en trois heures et ça va te coûter le même montant que si tu en avais mille. VERSTRICHT Tout de même, ça a marché pour toi parce que tu l’as présenté beaucoup… PEDRON Oui, et je pense même qu’on va continuer. Ça donne de l’espoir! (rires) Mais ENTRE, c’est magique! Les gens qui vivent cette expérience, ils veulent la partager. Parfois, les diffuseurs ont de la misère, mais ils essaient au boutte. VERSTRICHT Après l’avoir fait? PEDRON Oui. VERSTRICHT Parce qu’ils deviennent convertis? PEDRON Oui. Ils veulent que les gens vivent ce qu’ils ont vécu. INDEEP est aussi super politique, parce que ce sont des corps marginalisés à la base et je les considère comme des êtres humains qui ont autant de valeur que Monsieur député de je-ne-sais-pas-quoi. Pour moi, ils ont peut-être encore plus de valeur parce qu’ils ont une richesse d’expérience de vie, puis je travaille avec eux et je les paye. Je le fais parce que ces jeunes-là m’intéressent, parce que j’ai à apprendre d’eux. Je ne le fais pas pour revendiquer « Il faut s’occuper de ces jeunes! » Ce n’est pas mon discours. VERSTRICHT J’ai vu passer sur Facebook que tes demandes de bourses avaient été rejetées par le Conseil des Arts une vingtaine de fois… PEDRON Vingt fois consécutives! En recherche et création, depuis que je dépose – c’est-à-dire depuis 2006 – j’ai eu une seule bourse et c’était une pour une vidéo-danse en 2007. Et j’ai déposé deux fois par année, chaque année, et je n’en ai jamais eue. J’en ai eue en production, j’en ai eue au CALQ, mais… Pour LA LOBA, je ne l’ai pas eue non plus, alors que j’avais déjà des images, que le projet était déjà avancé. Je n’ai même pas voulu appeler pour savoir pourquoi. Mais je pense que mon travail est trop « art performatif » pour la danse. Il faut que j’applique en arts multidisciplinaires maintenant. VERSTRICHT Avoir gagné Le prix DÉCOUVERTE de la danse de Montréal en 2015 ne t’a même pas aidé? PEDRON C’est ce que tout le monde me disait : « Maintenant, c’est le temps d’appliquer aux bourses parce que tu as eu une reconnaissance publique. » Bien, non! (rires) Je n’en revenais pas! Je n’en aurai jamais. Il faut que j’arrête d’appliquer en danse. VERSTRICHT C’est drôle parce que c’est quelque chose qui revient encore souvent… J’avais fait une entrevue avec Lara Kramer et elle m’avait dit qu’il y a des gens qui lui disent « Ce n’est pas de la danse… » PEDRON Il y a quelque chose de très conservateur en danse. Je suis certaine que quand les gens de danse vont venir voir LA LOBA, ils vont me dire que ce n’est pas de la danse. Ça ne bouge pas assez. Je ne suis pas quelqu’un de de même. Ce n’est pas moi. Mais ce n’est pas pour autant que ce n’est pas de la danse.

VERSTRICHT Est-ce que c’est une préoccupation que tu as ou tu fais ce que tu veux? PEDRON Je fais ce que j’ai à faire. S’il y en a qui aiment, c’est tant mieux. Je le souhaite. S’il y en a qui n’aiment pas, ils n’aiment pas. Je ne suis pas dans la séduction de mon public. Avec ENTRE, c’est autre chose parce qu’on est dans une telle intimité que mon public devient l’œuvre, mais je ne suis pas dans la séduction. Je suis dans l’écoute. Je deviens le reflet de qui tu es et tu deviens le reflet de qui je suis parce que tu me sens et je te guide. C’est un jeu de miroir. C’est ça qui fait la profondeur de ENTRE. C’est une mise en abyme. Ça va loin. Ça me dépasse. Ce n’est plus moi. Je ne suis plus maître d’œuvre. VERSTRICHT Comment l’as-tu créé? PEDRON Au début, j’avais un truc avec de la technologie bien compliquée… Je n’ai jamais eu de bourse. Je me suis retrouvée avec une résidence mais j’avais zéro argent. Je savais que je voulais travailler sur la rencontre et l’intimité, puis après j’ai pensé « Si je mettais les gens de le noir… » C’est parti de là, parce que je n’avais pas d’argent, que j’ai dû faire sans rien. Puis, après coup, j’ai eu l’argent et j’ai pu monter toute la structure qui va avec. L’idée de mettre le spectateur à l’aveugle est venue parce que j’avais rencontré un aveugle six mois avant et j’avais été fascinée par l’écoute de son corps. Parce qu’il ne voyait pas, son corps est devenu très savant et ça m’a inspiré. Il m’avait demandé « Tu fais quoi comme métier? » Je lui avais dit « –Chorégraphe. –Qu’est-ce que c’est ça, ‘chorégraphe’? » Je me suis posée la question « Comment pourrais-je partager mon métier avec quelqu’un comme ça? » Ça a été mon déclic pour ENTRE. Quand je suis entrée en résidence, je n’avais pas d’argent, pas de matériel. J’ai fait « C’est ça que je vais faire! Je vais mettre le spectateur à l’aveugle et je vais lui faire vivre le mouvement autrement, comme il ne l’a jamais vu puisqu’il ne le voit pas. » VERSTRICHT Est-ce que cette personne-là a eu la chance de faire ENTRE? PEDRON Non. Il n’était plus là. VERSTRICHT Je ne sais pas si tu as lu le livre dans lequel on pouvait écrire à la sortie de INDEEP… J’ai resté environ une heure et je me sentais très bien. À un moment donné, il y avait un garçon qui était étendu par terre et je regardais sa main et, je ne sais pas pourquoi-- PEDRON Ah, c’est toi… VERSTRICHT --j’ai presque pleuré. PEDRON Quand j’ai lu ça, j’ai été touchée parce que j’ai eu la même sensation que toi : d’être dans une telle proximité, mais avec un inconnu qui est tellement vulnérable et tellement proche, puis que lui ne sait pas que tu es là, ça fait qu’il est abandonné… VERSTRICHT Il y avait quelque chose du sommeil, de voir quelqu’un dormir et ils n’ont aucun mur d’érigé pour se protéger. Ils sont vulnérables. Je suis parti peu de temps après avoir eu ce moment-là, parce que c’est un spectacle anti-dramatique et tout à coup, à la cinquantième minute, j’ai eu ce moment-là. Pour moi, c’était le point culminant, donc je suis parti. PEDRON Quand je dis que le spectateur va construire son propre temps, c’est exactement ça. Tu as pris la responsabilité de dire « Moi, je finis là-dessus. » Tu es devenu le créateur de ton œuvre à toi. Et je trouve ça très important. VERSTRICHT Ça fait combien de temps que tu travailles sur LA LOBA? PEDRON Deux ans et demi. VERSTRICHT Est-ce qu’entrer dans l’espace il y a une semaine à peine a changé quelque chose? PEDRON Ça connote. On ne peut pas y échapper. C’est puissant, un lieu. Ce lieu-là raconte déjà quelque chose sans qu’on n’ait rien fait. En même temps, je choisis d’aller dans des lieux qui ont une certaine couleur. Ce lieu a un certain vécu. C’est rare des bâtisses qui sont aussi vieilles à Montréal. Le poids de l’histoire, c’est important. Si je loue un lieu vacant, c’est aussi pour ça, donc j’accepte qu’il colore le travail. VERSTRICHT C’est quoi ton sentiment par rapport au lieu? Est-ce que tu es satisfaite de ce que tu as trouvé? PEDRON Je suis très satisfaite. Je trouve ça magnifique. C’était l’institut pour les sourds et muets du Québec, tenu par les sœurs. Il n’y a plus les sœurs, mais il y a un institut pour les sourds et muets qui est dans la bâtisse d’à côté. Ici, avant, c’était des locaux administratifs du Gouvernement du Québec. VERSTRICHT Et maintenant c’est vacant. PEDRON Et c’est chauffé l’hiver. À tes frais. C’est fou quand même, quand tu y penses. C’est quatre immenses étages. Tu pourrais loger la moitié de tous les sans-abris de Montréal. 20-25 septembre www.danse-cite.org 514.982.3386 Tarif unique : 25$ Going to Festival Quartiers Danses’s Programme triple at Cinquième Salle on Saturday night was like traveling to the past without experiencing nostalgia. The evening opened with Diane Carrière’s reconstruction of ABREACTION (1974), titled Et après… le silence for this version. What first strikes us is how far music for dance has come over the past forty years. Here it almost sounds parodic in its likeness to the cheaply dramatic scores for low-budget straight-to-video productions. It is even more dated than the affected modern movement. Dancer Sébastien Provencher, always reliable, uses all of his length as he extends his arms as far as they will go. Nothing to do about it though: isolated screams are always funny, no matter what they’re supposed to communicate. Carrière joins Provencher for the second half of the piece. How satisfying it is to watch older people dance. It is unfortunate that Carrière was otherwise so precious with her material, refusing to shake off the music or the video footage that anchored Et après as a dusty historical document instead of truly resurrecting it to make it relevant for a contemporary audience. Followed Victoria choreographer Jo Leslie with her duet Mutable Tongues. We’d already had the chance to see Leslie’s work at Tangente in 2011 with Affair of the Heart, an understated solo for Jacinte Giroux, a Montreal dancer whose speech and movement have been transformed by a stroke. Here again we found Giroux, this time accompanied by Louise Moyles, a dancer and storyteller from Newfoundland. Moyles walks into the room alternately speaking English and French. This self-translation makes everything she says sound phony. Giroux is lying face down on the stage, just outside the spotlight. She tells Moyles she’s had a stroke, but Moyles doesn’t listen, tells her to “get up” then to “lie down.” She is verbally abusive in a way that ableist culture is always abusive, even when it doesn’t use words, when instead of saying “get up” it just puts a staircase. We think of how choreographer Maïgwenn Desbois had subverted this idea by letting her neurodiverse dancers briefly choreograph her in Six pieds sur terre. With its burnt orange dresses, black tights, and heavy reliance on theatre, Mutable Tongues also feels a bit dated, not to mention that it is even more didactic than Carrière’s piece (which used voice-over to bring up such topics as hand-to-hand combat and PTSD). It reminded me of Chanti Wadge’s The Perfect Human (No. 2), which found its inspiration in dancers answering the question “Why do you move?” A young woman had walked to the front of the stage and screamed “I move because I hate talking!” I would turn it around and say that I go see dance because I love when people shut the fuck up. That’s certainly when Mutable Tongues is at its best. The evening concluded with Howard Richard’s Beaux moments, a piece for four women that was the most contemporary thing we got to see, though even then it was more akin to the beginnings of contemporary dance. There were moments that recalled Ginette Laurin’s work: the legs that were lifted while turning out at a 45-degree angle before the heels of the shoes thumped back down against the floor; the sideways lifts where a woman would throw herself under her partner’s arms so that she could lend on their thighs. However, Richard’s movement was less verbose and neurotic than Laurin’s. In the duets, the women also looked as if they were in each other’s way rather than working together. But even the electronic music and the costumes (black sleeveless dressed with red short-heeled shoes) had something of O Vertigo about them. There was also a solo set to Cat Power’s “The Greatest” that failed to fit with the rest of the piece as it flirted with the contemporary in a So You Think You Can Dance way.

The most positive aspect of the triple bill was the chance to see middle-aged women dance, including Estelle Clareton. But, if we were to base an opinion on this evening alone, we would be inclined to say that we’d rather watch older people dance rather than choreograph. Maybe La 2e Porte à Gauche had the right idea with Pluton. www.quartiersdanses.com September 6-17 514.842.2112 / 1.866.842.2112 Tickets: 25$ / Students or 30 years old and under: 20$ WARNING: spoilers.

La crème de la crème of Quebec celebrities (Sébastien Benoit) and their children (Sébastien Benoit’s child) were at the Bell Centre Wednesday for the first of a four-day run of Ice Age on Ice. The show begins with a squirrel finding an acorn. He buries it in… something and a rocket goes off. Follows a parade of the main characters of Ice Age on Ice: a sloth, a male and a female mammoth, two possums, a cougar, and their monkey friends. Though the dialogue is in French, all the songs are in English, so they sing “It’s your birthday / Happy birthday!” to mister mammoth in a surreal scene, like if one witnessed the 1990 live action Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles ice skating. (Did they do that yet?) The cougar’s back legs are paralyzed, but luckily they slide easily against the ice. The mammoths are also held up by wheelchairs, so it’s nice that there’s a positive message against ableism. Comes the triggering factor: the aforementioned acorn stuffing caused a volcano to wake up and it’s threatening to wipe out our heroes’ party with its lava. The sloth recalls a legend about an icy berry that freezes everything it touches, which seems like a rather simplistic solution to global warming. This gets exemplified by a dozen abstracted glittery snowflakes with Mohawks and a bird who spin to show they’re happy about the cold, which lets us know they’re not from Quebec. As the show is aimed at children, it’s not surprising to notice some slapstick, like when the sloth tries to catch a snowflake with its tongue and falls down. Children love to see people fall. Adults do too, but only when it’s not on purpose. So our heroes decide to go on a hunt for the icy berry in order to throw it in the volcano and freeze it over. The lady mammoth stays home though because that’s where women belong. There is also the inevitable complication in the shape of a female fox who wants the berry for herself because it would allow her to remain frozen in youth because women are vein and don’t care about being burned alive by lava just as long as they look good all the while. Enters a squirrel who is also female, which we know because she is limp-wristed, waves her arms around a lot and wears makeup, as lady squirrels do. She’s an acorn-digger who needs a male squirrel so he can give her his nuts because she can’t get them herself. Her boobs get in the way. Except that mister squirrel realizes he lost his nut and has a psychotic breakdown in what is by far the highlight of the show. He hallucinates sixteen acorns dancing around him in what can be best described as a psychedelic drug trip. Then there’s the Zamboni. No, wait… It’s just the mammoth’s big ass! I love fat jokes. Anyway, they get the frozen berry, the fox tries to steal it but fails by losing it in a hockey match and apologizes for her behaviour. She’s surprised that our heroes would still want to hang out with her, which is understandable because what a sausage party! But then it turns out that two possums ate the frozen berry. Why our heroes would leave the life-saving berry to animals who were clearly not aware of their plan is beyond me, but it doesn’t matter because it becomes obvious that the berry has no magical powers since the possums don’t turn to ice. Take that, magical-thinking solution to global warming! That’s when mister mammoth has an idea: what if they caused a snow avalanche that would put out the volcano by jumping up and down? (Does this even make sense scientifically?) He asks his lady what she thinks and she replies that she believes in him because she’s a supportive woman with no opinion of her own. I’ll let you guess how it ends. The show follows a simplistic structure: plot, figure skating, plot, figure skating, ad nauseam; like if Xavier Dolan was into the Ice Capades instead of slow motion. As with stories in contemporary dance, the two fail to connect in any meaningful way. All we perceive is the poverty of dance as a storytelling medium. Do we really need stories to make us swallow everything, including figure skating? There’s something almost patronizing about it, like Ice Age on Ice is just using characters kids already know and love to shove figure skating down their throat. As Spice World already pointed out back in 1997, it doesn’t matter what happens. Hell, nothing even needs to happen. All we need are those recognizable faces and we’ll eat it up. Ice Age on Ice did give me a few ideas as to how contemporary dancers could make more money though:

August 24-27 www.evenko.ca 1.855.310.2525 Tickets: 29.25-100.50$ As Festival TransAmériques draws to an end, spectators gather to watch nineteen individuals most of whom have no formal dance training take over the large stage of Monument-National and perform in French choreographer Jérôme Bel’s Gala. Cast in Montreal, they represent the diversity of the city: different ethnicities, different ages, different genders, different abilities, different body types.

The show opens with a long, shitty PowerPoint of different empty stages around the world, from the ancient to the technologically advanced, from the modest to the luxurious, from the small to the large. But their essence is the same: on one side, a group of people is meant to perform and, on the other, another group is meant to watch. In that space and in that relation, something could happen. We could be in any of these theatres, but we are in this one. In any case, what matters is the performance. The performance itself begins with a ballet section, a parade of the nineteen dancers performing a pirouette. First up is professional dancer Allison Burns so that the audience gets to see what the movement should actually look like as a reference point. The following non-dancers adapt the movement to their bodies, customize it for their skill level. While dancers can pick up a maximal set of cues because of their training, children and untrained adults only pick up the few that most characterize the movement for them. For example, a young boy simply lifts his arms over his head, actually holding hands, and spins. The exercise is then followed by a grande jeté. However, what comes across is that it’s not just a matter of skill, but also a matter of comfort with one’s body. Some performers come across as uncomfortable, which stiffens their movement. This is especially important because I feel it plays a large part in the discomfort that many experience with contemporary dance, even as spectators since the audience is always projecting itself onto the dancers. This explains the issues that some have with nudity onstage. Most people couldn’t allow themselves to do what dancers do alone in their own home, let alone on a stage in front of hundreds. This also partially explains why the children stand out in the improvised dance section. The cliché exists for a reason: they’re not as socially conditioned yet, they are less self-conscious, and they have fewer preconceived ideas about what dance is and what it’s supposed to look like, so their dance is freer. Édouard Lock said that the difference between dancers and non-dancers is in the legs. It’s visible here. Non-dancers make up for it by running around and moving their arms excessively. Unable to hide behind their skills, the non-professional dancers’ personality shines through: there’s the ham, the shy one, the funny one… The bows section, also using the parade structure, punctuated with applause for every single performer, makes one feel like Bill Murray’s character in Groundhog Day. Bel deals with the shortcomings that ableism imposes on all of us by having different performers choreograph for the entire group, the way Maïgwenn Desbois had in Six pieds sur terre. Seemingly no one expected a fat man to come out twirling the baton while the others keep dropping theirs. Everyone has something to offer. Despite its lazy structure, Gala is an undeniable crowd-pleaser. When the audience stood up for a warm standing ovation, it was the non-professional dancers they were applauding. It seems people like to see individuals who look like them onstage. Isn’t that surprising? June 7 & 8 at 8pm www.fta.ca 514.844.3822 Tickets: 34-50$ When the door opens, the action is already unfolding. On the other side of the door, the world is coated in a pinkish hue. A continuous loud high-pitched sound is oozing out. Through the spectators who have already found a seat, we see five dancers moving: Meryem Alaoui, Ellen Furey, Jolyane Langlois, Ann Trépanier, and Amanda Acorn, choreographer of multiform(s).

The audience is sitting on stands surrounding all four sides of the white stage, lending the performance the feel of a sporting event. Appropriately, the dancers are wearing sneakers. The rest of their outfits falls into a contemporary dance trend: nice bordering on fancy clothes that are joyfully mismatched. Whenever spectators are allowed to sit on multiple sides of the stage, I am always surprised to notice that the feeling of the proscenium stage remains. It reminds me that, despite the conventions of theatre, dance is truly three-dimensional and that it is only ever possible to see from one’s own perspective. Though the movement differs from one performer to another, it answers to the same constraints: their bodies are forever in motion and involved in repetitions. Back and forth, from one side to the other, like a pendulum. This swinging often leads the cylindrical body into rotations. They reminds us of mechanical toys that inevitably have a limited movement range, except that the dancers’ movement changes over time, ever so slightly, but undeniably. This rocking motion can at times induce motion sickness, an experience the spectators apparently share with the performers. It is an exercise of endurance for the dancers that is hypnotic for the audience. The performers converge to the middle of the stage, their movement becoming synchronous and picking up speed. Synchronicity focuses the gaze; dissimilarity diffuses it. Synchronicity feels light. It’s like forgetting yourself. Yet when one of the dancers falls out of it, it’s her we’d rather be. She’s the one who looks free. With its clear concept and perpetual motion, multiform(s) shares many similarities with Henderson/Castle: voyager by Ame Henderson. However, in voyager, dancers can’t repeat any movement so that the end result is less defined, more eclectic. In multiform(s), the repetitions appear to be an outlet, like in Julia Male’s solos. As in Guilherme Botelho’s Sideways Rain and the walking that takes up most of Olivier Dubois’s Tragédie, we also feel that this could go on forever, that in fact it has been. Different images emerge depending on the body parts that the movement brings into action. Front to back movement looks like prayer; sometimes one might even say like divine possession. Lunges inevitably remind one of the repetitions involved in exercise. And, though the arms never carve the infinity sign in the air, it is seen everywhere. One is even inclined to believe that the dancers might be immortal. June 5-7 at 9pm www.fta.ca 514.844.3822 Tickets: 30$ / 30 ans et moins: 25$ De Pluton – acte 1, je garde un souvenir d’un spectacle tout en douceur. Ce que La 2e Porte à Gauche nous réserve pour ce deuxième mariage de jeunes chorégraphes avec des interprètes plus âgés s’avère toutefois plus corrosif.

Il est étonnant que la pièce de Frédérick Gravel soit celle qui s’aligne le plus avec le premier acte, probablement dû au fait que Paul-André Fortier la danse. Les genoux et les coudes fléchis, il se déplace du côté cour au côté jardin en pivotant, les semelles de ses espadrilles rouges glissant contre le sol. Même s’il épouse le corps recroquevillé de Gravel, ses mouvements sont plus soignés et fluides. Je me rends compte que, jusqu’à maintenant, je ne l’ai vu que dans des contextes où il dansait ses propres chorégraphies, de sorte que j’oublie parfois que c’est Fortier que je regarde parce que je ne reconnais pas sa posture habituelle. Je ne reconnais pas tout à fait la chorégraphie de Gravel non plus, qui se fait ici beaucoup plus doux et subtil. C’est la beauté de ce projet. Catherine Gaudet s’était démarquée avec son solo créé pour Louise Bédard pour acte 1. Il n’est donc pas surprenant de le retrouver ici. Gaudet continue d’y explorer l’un de ses thèmes fétiches, soit la duplicité de l’humain. Bédard est d’abord dos au public en arrière scène, ses expirations flirtant avec les grognements, invoquant simultanément les bébés naissants de Je suis un autre (2012) et les monstres d’Au sein des plus raides vertus (2014). Elle est une bête qu’on cache loin des regards. Ses doigts arthritiques ressemblent plus à des griffes qu’à une main. Lorsqu’elle nous fait face, un sourire se plaque sur son visage tremblotant. Elle veut paraître en contrôle, mais la surface ne peut que craquer, comme toujours chez Gaudet. Ce n’est pas la part animale ou monstrueuse de l’humain qui transparaît ici, mais les troubles de santé physique et mentale. On peut y voir la maladie de Parkinson ou celle d’Alzheimer. C’est à mon humble avis ce que Gaudet a fait de mieux. Après l’entracte, les spectateurs se retrouvent des deux côtés de la scène pour la pièce de Mélanie Demers, un duo pour Marc Boivin et Linda Rabin. Le musicien Tomas Furey s’avance à un micro sur scène, y va d’un « 3, 4 » mais ne chante pas. C’est Boivin et Rabin qui alterne respectivement « New York, New York » et « Let Me Entertain You », rivalisant d’exhibitionnisme performatif. Ils en sont agressants. Comparativement, Furey nous charme avec son silence, nous offrant une sortie de secours essentielle. C’est la pièce la moins séductrice, la plus abrasive de Demers à ce jour. On pourrait dire la même chose de celle de Katie Ward, un solo pour Peter James. Des chaises sont éparpillées sur la scène et les spectateurs sont invités à y prendre place. Soir de première, c’est une vingtaine d’adolescentes qui se sont prêtées au jeu, créant une atmosphère particulière. Pour ceux d’entre nous qui ont été témoins des explosions verbalement violentes de James dans des pièces comme Mygale (2012) de Nicolas Cantin, nous devons nous retenir pour ne pas crier « Ne le laissez pas s’approcher de ces jeunes filles! » Heureusement, nous retrouvons plus le ludisme de Ward marié au minimalisme de James, déjà aperçu dans sa collaboration avec Cantin pour Philippines (2015). En fait, cet opus ressemble plus à du Cantin qu’à du Ward. Aucune illusion ici; James joue avec le théâtre, littéralement, c’est-à-dire avec la salle de spectacle elle-même. Les lumières éclairent tout l’espace. Il secoue la rampe des escaliers, il modifie la lumière à la console d’éclairage, il manipule les rideaux en nous disant, « Ça, c’est vrai. » Il lance une balle contre le mur juste pour nous rappeler que le mur est là, pour que l’espace s’impose plutôt que de s’effacer sous l’effet de la performance. C’est dans ses interactions avec le public qu’on approche de la magie, comme lorsqu’il prétend dévisser un tube invisible du ventre d’une des adolescentes pour ensuite le déposer sur une chaise. « Ce n’est pas nous qui créons la magie, » semble-t-il vouloir dire. « C’est vous, spectateurs. » 28-30 mai à 19h www.fta.ca 514.844.3822 Billets : 40$ / 30 ans et moins : 34$ |

Sylvain Verstricht

has an MA in Film Studies and works in contemporary dance. His fiction has appeared in Headlight Anthology, Cactus Heart, and Birkensnake. s.verstricht [at] gmail [dot] com Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed