|

C’est un spectacle. I don’t know why anyone would expect anything else when going to Place des Arts to witness Nederlands Dans Theater passing through Montreal for the first time in over twenty years. For the occasion, we were treated to a Crystal Pite sandwich on Sol León & Paul Lightfoot bread. Sehnsucht opens and ends with a man bowing in a frog-like position at the front of the stage. In the background, a straight couple engages in a pas de deux in a cubic room. Like the needles of a clock, their legs and arms stretch out and rotate around a two-dimensional axis. Their movement is fast-paced while that of the man in the foreground is fluid but sculptural in its slowness and poses, as though time passed more slowly for those alone. The room spins vertically, so that the dancers sometimes appear to defy gravity like Fred Astaire in Royal Wedding, sitting on a chair that hangs from a wall, for example. The choreographers use this magical element to charm the public without pushing it to the point where it would transcend its gimmick. The room disappears and thirteen dancers come out for the middle section. They dance synchronously in a manner that is reminiscent of Ohad Naharin’s Hora: the athletic bodies of the dancer maintain the legs of ballet (pirouettes included); however, while the upper bodies in Hora could be said to fall under a post-modern aesthetic, here they are more akin to music video choreography. (The synchronicity might partially be to blame for this.) The fast pace of the choreography follows along the gaudiness of Beethoven’s Symphony Nr. 5, resulting in the kind of comic effect that the Looney Tunes capitalized on.

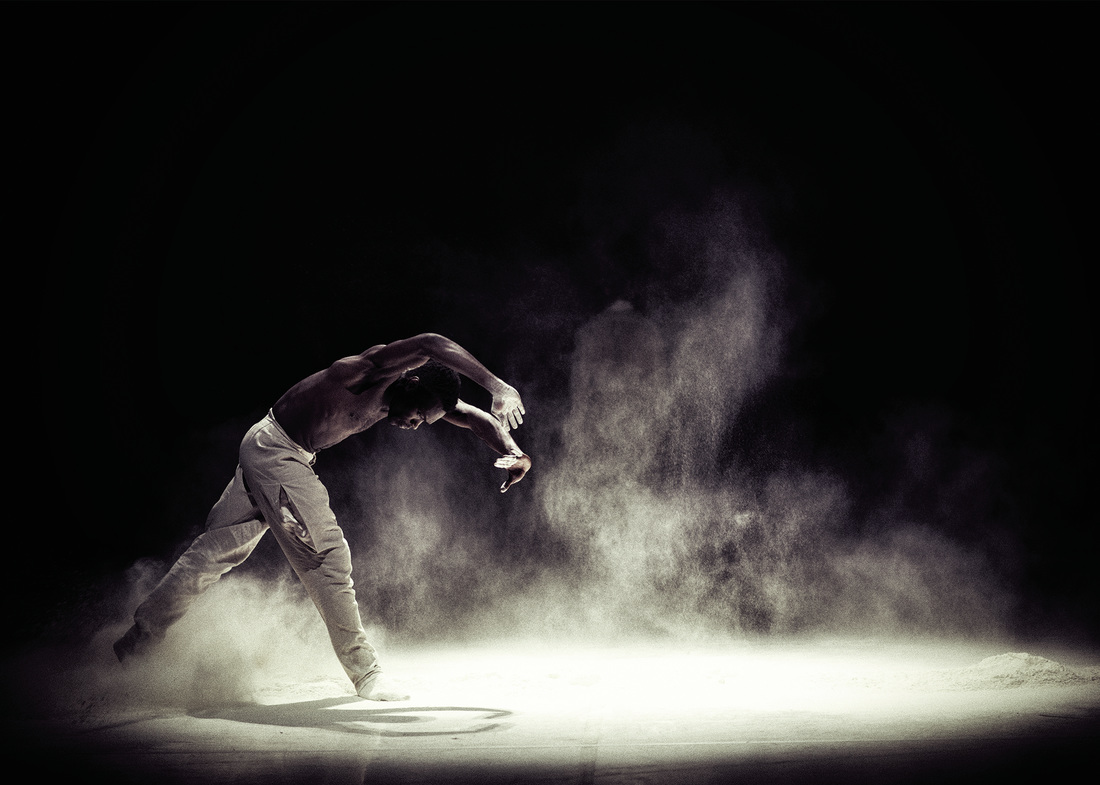

Canadian choreographer Pite offers the strongest piece of this triple bill with In the Event. Set against a grey sandy backdrop, eight dancers appear like a group on an expedition through the darkness of a foreign planet. The world around them feels potentially threatening, from their shadows moving along the walls of a cave to the rumbling on the soundtrack and the lightning that shatters the background. However, the dancers are in it together, cooperating as a group, sometimes literally forming a human chain with their limbs. The movement is elastic, round, and refreshingly ungendered. The dancers slide against the floor, sometimes even float above it. A solo provides the piece with a dramatic ending as a man’s hands frantically search the floor and reach for his chest and throat as if he were choking. For Pite, being alone looks like being lost. León & Lightfoot fare better with Stop-Motion, a piece for seven dancers that is gothic-looking with its black background, white and beige pants, white walls, floor and powder, and black and white video projection. The dance is better served by Max Richter’s moody modern classical music. In solos and duos, the agility of the dancers is used to evoke emotion rather than being an end in and of itself like in Sehnsucht. However, the choreographers once again go for synchronicity for the group section; rather than intensifying the effect, it comes across as lazy and dilutes it. As the piece ends, some curtains are lowered while others after are lifted, and the lighting grid also comes down. There is the feeling that León & Lightfoot are doing this just because they can. With this triple bill, they show that they have the dancers and the means to make great art, but they fail to prove that they have the will. November 1-5 at 8pm www.dansedanse.ca 514.842.2112 / 1.866.842.2112 Tickets: 41.50-70$

0 Comments

Je me souviens parfaitement du premier spectacle de danse contemporaine que j’ai vu à l’âge de 18 ans. Il m’a marquée à jamais et a ouvert en moi la conscience que ce qui est désagréable peut s’avérer fantastique et la certitude que ça vaut la peine de rester ouverte aux choses les plus étranges. C’était Zarathoustra de la Compagnie Ariadone de Carlotta Ikeda. Du butō. Je l’ai vu du poulailler de l’Opéra de Montpellier où je faisais mes études à ce moment-là. C’est du butō classique des premières années, avec des corps à moitié nus couverts d’argile blanche, complètement recroquevillés, les membres rétractés, les yeux révulsés… Les danseuses restaient prostrées au sol dans des mouvements minimalistes et je me disais : « C’est quoi, ce foutage de gueule? » Je fulminais. Mais bon, même quand je suis en colère, je ne sors pas de la salle parce que j’ai toujours l’espoir que quelque chose de bon va se passer. Et, effectivement, quelque chose s’est passé. À la fin du spectacle, du sable tombait en pluie fine sur la scène sous des éclairages dorés et subitement, j’ai été éblouie. Pas au sens « flabbergastée », mais profondément touchée. Par quoi? Je n’en savais rien, mais je suis sortie de là tellement sous le choc que j’étais sans voix, les larmes aux yeux. Je savais que quelque chose de merveilleux et de fondamental venait de se produire. C’était en 1981.

Les années 1980-90 en France Avant ça, j’avais adoré Maurice Béjart. J’avais des posters de ses danseurs dans ma chambre. Je me souviens particulièrement de La Flûte enchantée… des belles lignes néoclassiques. Et là, un autre monde s’ouvrait soudain à moi. Cette année-là était la première du Festival Montpellier Danse et j’ai eu la chance d’avoir accès à tous les spectacles parce que mon chum y travaillait comme éclairagiste. J’ai assisté à des spectacles extraordinaires qui m’ont beaucoup marquée comme Carolyn Carlson, avec Blue Lady, ou le Nederlands Dans Theater. Je ne sais plus ce qu’il dansait, mais ça m’avait beaucoup plu aussi. À cette époque, j’allais aux répétitions publiques de la compagnie de Dominique Bagouet et je prenais des cours de danse avec de jeunes chorégraphes professionnels dont je filmais parfois le travail. Dans les années 1990, je suis devenue journaliste et je me suis spécialisée en arts et culture. Je couvrais la danse de temps en temps et participais à des ateliers de médiation culturelle dès que j’en avais l’occasion. J’ai encore en mémoire un fabuleux stage avec Maryse Delente qui est aujourd’hui à la tête du Centre chorégraphique national de La Rochelle… Premiers souvenirs au Québec J’ai immigré au Québec un 26 avril. Le 29, c’était la Journée internationale de la danse et il y avait des cours gratuits un peu partout en ville. J’en ai pris le maximum et me suis rendue à un atelier avec Benoît Lachambre au fin fond d'Hochelaga-Maisonneuve. Le nom me disait quelque chose, mais je ne le connaissais pas. J’y vais, et là, il commence à nous faire danser avec les yeux. Je me dis : « Mais, c’est quoi ce truc? » Je trouvais ça complètement débile et j’ai profité de gens qui quittaient le studio pour filer moi aussi. Aujourd’hui, Benoît fait partie des artistes qui m’intéressent le plus et je donnerais cher pour participer à un de ses ateliers sur l’hyper éveil des sens. Je n’étais juste pas prête. Premières critiques La toute première critique que j’ai faite, c’était La Pornographie des âmes, en avril 2005. Je voyais déjà de la danse depuis longtemps, j’écrivais une chronique d’annonces arts et spectacles dans le journal L’Actualité médicale, mais n’avais jamais fait de critique. J’avais adoré La Pornographie des âmes qui m’avait émue aux larmes et ma critique était très positive. Ensuite, j’ai critiqué de manière plutôt sanglante un spectacle que j’avais trouvé détestable. Je n’y allais pas de main morte à l’époque. Je faisais des effets de style autant pour encenser un spectacle que pour le descendre. Comme beaucoup de jeunes critiques, je manquais de distance, de perspective, et je cherchais à me valoriser avec de belles formules. La critique, ça donne un pouvoir énorme et on peut facilement en abuser. Ça faisait cinq ans que j’avais immigré, j’avais beaucoup écrit en psycho/spiritualité/sociologie dans un magazine alternatif, je voulais me faire une place en danse, mais personne ne me connaissait. J’avais d’ailleurs souvent du mal à obtenir une invitation au spectacle. Et comme j’écrivais dans DFDanse, qui s’adressait surtout aux spécialistes, je ne prenais pas de gants. Ceci dit, si ma façon de dire les choses était critiquable, ma vision était quand même assez juste. Je me souviens que Francine Bernier [la directrice générale et artistique de l’Agora de la danse] m’avait dit : « Oh la la, toi alors, tu es culottée, hein! Mais tu écris noir sur blanc ce que tout le monde pense tout bas. » Cela m’avait confortée dans mes choix, mais je me questionnais quand même sur mon droit de critiquer aussi sévèrement des œuvres et des artistes. Alors je me suis inscrite à une formation sur l’élaboration du discours en danse contemporaine qui était offerte par le Regroupement québécois de la danse. J’y ai acquis des outils qui m’ont aidée à m’améliorer. Plus médiatrice que critique Dans DFDanse, qui était surtout lu par des gens du milieu, je pouvais faire preuve d’une intransigeance qui s’est adoucie spontanément quand j’ai commencé à écrire dans Voir. Je me rendais compte que je m’adressais à un plus grand public et que je ne pouvais pas tenir le même type de discours si je voulais que les lecteurs aient envie d’aller voir de la danse. Parce que mon objectif de base, ça a toujours été de démocratiser la danse et de la promouvoir. Pas de promouvoir des spectacles, comme se l’imaginent beaucoup d’artistes quand ils traitent avec des journalistes, mais de promouvoir la danse. Au fond, je me considère plus comme une médiatrice que comme une critique. J’ai d’ailleurs plutôt pratiqué le journalisme dans une perspective de médiation pour initier le public à la danse contemporaine que dans une perspective d’analyse critique pour faire évoluer la discipline. Le média dans lequel j’écrivais se prêtait bien à ça. Il faut dire aussi que l’appréciation d’une pièce dépend de tellement de facteurs : de la salle, de l’état dans lequel tu es, de ce que tu as vu la veille, du sujet qui résonne ou pas en toi, de toutes sortes d’affaires… Par exemple, La Pornographie des âmes qui m’avait tellement touchée à Tangente, je l’ai revue à l’Usine C et j’en ai vu tous les défauts. Et puis, je suis retournée la voir à la Cinquième Salle et j’ai retrouvé les émotions que j’avais ressenties à la première. Les exigences d’une spécialiste On me demande souvent si je me lasse à force de voir tant de spectacles, si l’intensité de ce que je peux ressentir diminue au fil du temps. Pas du tout! Ce qui diminue, c’est l’intérêt pour certaines formes et ma patience face au travail inabouti. Parce que je trouve qu’au Québec, et c’est ainsi pour toutes sortes de raisons, beaucoup de spectacles sont le résultat d’une recherche mais pas encore vraiment des œuvres. Et forcément, il arrive un temps où je n’ai plus vraiment envie d’aller voir la recherche d’un artiste qui pense avoir réinventé la roue alors qu’il fait ce que des dizaines, voire des centaines, d’artistes ont fait avant lui. Ça arrive particulièrement chez les jeunes artistes qui manquent de culture chorégraphique. J’ai mis longtemps un point d’honneur à aller voir le plus possible toutes les productions, mais ça fait beaucoup de soirées passées au spectacle. Alors aujourd’hui, oui, il y a des artistes émergents que je ne connais pas encore, mais je les découvrirai quand ils seront un peu plus matures et je serai plus réceptive à leur travail. C’est mieux pour moi et pour eux aussi. Je vais au spectacle pour élargir ma conscience, ma perception du monde et de moi-même. C’est pour ça que les œuvres plus mystérieuses ou a priori plus hermétiques m’intéressent : ce sont elles qui m’ouvrent le plus de nouvelles portes. En revanche, je trouve généralement plutôt vides les spectacles en forme de divertissement. J’admets qu’ils sont nécessaires et qu’ils ravissent un certain public, mais pour moi, ils sont stériles. Trouver du sens au-delà de la raison Le sens d’une œuvre de danse n’est pas forcément formulable, il ne passe pas nécessairement par un raisonnement. Je suis sûre qu’il y a des œuvres qui ont pris des années pour se frayer un sens à travers moi et j’ignore peut-être même quelle résonnance elles ont eue en moi parce que je n’ai pas forcément fait le lien entre quelque chose qui avait affleuré à ma conscience et un spectacle vu quelques années plus tôt. Mais je suis convaincue qu’il y a des œuvres qui agissent sur moi de façon durable, qui sédimentent quelque chose de l’ordre du sens et de la conscience au-delà de ma pensée. À ce propos, j’ai réalisé des entrevues avec un psychanalyste et une psychologue dans le cadre d’un article sur l’enfant-spectateur que j’ai écrit en 2015 pour un gros dossier sur la danse jeune public que m’avait commandé le Regroupement québécois de la danse. Je me demandais quel bénéfice il pouvait y avoir pour un enfant à assister à un spectacle de danse. Il en ressort que l’on reçoit la danse en premier lieu avec le corps, que l’abstraction favorise l’ouverture et l’activité de l’imaginaire et que l’enfant est un terreau particulièrement fertile parce qu’il n’est pas encore formaté. Il crée du sens à partir de la danse, qu’elle soit abstraite ou narrative, et cela favorise sa construction identitaire. Pour les adultes, c’est pareil. La danse est une affaire de partage : l’énergie du public nourrit les danseurs sur scène et le regard du spectateur complète l’œuvre. Le quatrième mur est plus poreux qu’on ne le pense. En ce sens, le spectateur n’est pas un simple consommateur de culture. Il est responsable de son corps, de ses perceptions et de son degré d’ouverture à une œuvre. Ça peut paraître un peu ésotérique comme discours, mais pour moi c’est une évidence.

Quite Discontinuous, photo by Menno van der Meulen Quite Discontinuous, photo by Menno van der Meulen I didn’t watch Eurovision this weekend but I did go to Tangente to see Dance Roads, so let’s pretend that it’s the dance equivalent of Eurovision. In competition: Wales, the Netherlands, Canada, Italy, and France. Representing Wales, Jo Fong with Dialogue - A Double Act A video projection where the public sees itself in real-time, as in a mirror, which reminds me of the Belgian theatre company Ontroerend Goed’s Audience (and this even though I haven’t seen it). On stage, six chairs, two of which will find seaters, the female performers of Dialogue - A Double Act. They provide the suggestion of a performance, a sort of low-energy runthrough, like Michèle Febvre in Nicolas Cantin’s CHEESE. They often explain the performance instead of or just before actually doing it, like Andrew Turner had in Duet for One Plus Digressions. All this to say that it’s as charming as the performers are, but leaves us with a feeling of déjà-vu. Representing the Netherlands, Jasper van Luijk with Quite Discontinuous An athletic duo for two men with lots of floor work, which could make us think of breaking, but the moves are decidedly contemporary. The dancers are agile and the partner work is inventive. The relationship between the performers remains ambiguous. There seems to be a desire for connection, but both are on their own trajectory so that there is a difficulty in connecting. It might even be impossible. After one lies on the ground as though dead, the other shines spotlights on him, as an homage to the other and the desire for connection with him in spite of its unfeasibility. Representing Canada, Sarah Bronsard with Ce qui émerge après (4kg) A strange creature appears in obscurity at the back of the stage. We imagine there’s a dancer under there, though we can’t even figure out in what position they are. Soon we are able to make it out: it is her dress worn upside down, hanging off her body. She drops it on the floor, leaving her with a black pant-and-shirt combo. This is significant because Bronsard dances the flamenco but, like she leaves the typical dress behind, so she does with other elements of the dance. For example, she performs to ambient music and a dozen percussive contraptions with Mason jar lids for drums. As such, it’s hard to anticipate where the piece will go at any given moment, casting flamenco in a new light. Representing Italy, Andrea Gallo Rosso with I Meet You… If You Want Another duo for two men, which begins with them pushing each other’s back repeatedly, a rather lazy display of antagonism that unfortunately ends as soon as it gets more creative. In the second section, they evolve independently before falling into partner work for the third act. They end with the choreographic find of the piece as the two men, standing back to back, slide against each other to embrace on one side before sliding against each other’s back and embracing on the other side in a loop. Still, the piece lacks clarity. Representing France, Teilo Troncy with . je ne suis pas permanent . It begins quietly, with but a bit of a light on a sole woman. Soon, we hear music, but as though it is coming from a great distance. The dancer seems happy about it. The music comes in full force and she can finally do her jazzy dance with great energy. When the soundtrack disappears, she is left alone, humming as if trying to remember what she must do, psyching herself up. However, the grandeur of her movements danced to silence makes her look as though she’s having a meltdown. Things don’t seem to be going wrong technically as much as mentally. And the winner is… The Netherlands! Because it’s refreshing to see a contemporary dance piece that actually has dance in it. The Netherlands might seem like the obvious choice as it is the crowd-pleaser of the bunch. One might say that it’s not a particularly daring choice from the judges, but then again none of the pieces were especially daring either, so it might be fitting. www.danceroads.eu www.tangente.qc.ca  Levée des conflits, photo by Caroline Ablain Levée des conflits, photo by Caroline Ablain As my years as a dance critic pile on, it’s probably to be expected that I see more and more works I’ve already seen. This year, I can think of at least five off the top of my head. The one that most stood up to a repeat viewing was Matija Ferlin and Ame Henderson’s The Most Together We’ve Ever Been. I took the bus to Ottawa to see it just as a snowstorm was hitting the city. The ride ended up taking four hours. I barely had enough time to shove some of the worst food I’ve ever had in my mouth before running over to Arts Court, an old courthouse that has been turned into a beautiful art space. And, as soon as the show started, I knew it was all worth it. Back in Montreal, Israeli choreographer Sharon Eyal made a much-anticipated return after six years with Corps de Walk, a show she created with her partner Gai Behar. The uniformity she imposed on the twelve dancers of Norway’s Carte Blanche was oppressive and disturbing. It was its own indictment of homogeneity. At the Biennale de gigue contemporaine, the always reliable Nancy Gloutnez stood out yet again. With Les Mioles, she borrowed from classical music and became a conductor, turned her dancers’ feet into instruments, and composed a score reminiscent of Steve Reich in its obsessive build-up. After years of being one of the most rigorous emerging choreographers in Montreal, Sasha Kleinplatz has now fully emerged with Chorus II. The audience stood above six male dancers who swayed between demonstrations of physical strength and chill-inducing vulnerability. It is now up to venue artistic directors everywhere to shine on Kleinplatz the spotlight she so clearly deserves. Speaking of which, 2013 was the year of Agora de la danse. They probably had their best programming since I started following dance. It all began with Karine Denault’s Pleasure Dome, in which musicians and dancers explored pleasure without ever lazily resorting to shortcuts. Rather, she allowed the meaning of the work to emerge on its own and for Pleasure Dome to impose itself by the same token. It was followed by When We Were Old, a duo by Québec’s Emmanuel Jouthe and Italy’s Chiara Frigo (presented in collaboration with Tangente). The choreographer-dancers managed to bypass every single contemporary dance cliché that usually occurs as soon as a man and woman are onstage. In each and every moment, their encounter felt fresh and sincere. Agora ended the year with Prismes by Benoît Lachambre, who a month later would win the Montreal Dance Prize. Created for Montréal Danse, Prismes explored the effect of light on perception in a chromatic environment, as well as the fluidity of gender. Lighting designer Lucie Bazzo outdid herself for this highly experiential work. At the Festival TransAmériques, it was French choreographer Boris Charmatz who stood out with Levée des conflits, an opus of twenty-five movements repeated as a canon by twenty-four dancers. From the simplicity of the choreography to the high number of performers, Levée des conflits impressively hovered between minimalism and excess. I spent the summer in Iceland, where my trip ended with the Reykjavík Dance Festival. There, Norway’s Sissel M Bjørkli presented one of the most singular shows I’ve ever seen with Codename: Sailor V. It took place in a tiny space, barely big enough to seat fifteen. The smoke that filled the room along with Elisabeth Kjeldahl Nilsson and Evelina Dembacke’s intensely saturated coloured lighting blurred the edges of everything. Inspired by anime, Bjørkli created an alter ego for herself and through imaginative play managed to turn an office chair into a spaceship. That shit was magical. So was Nothing’s for Something by Belgium’s Heine Avdal and Yukiko Shinozaki, which opened with a ballet for six curtains, each suspended by six huge helium-filled balloons. Set to classical music, it was reminiscent of Disney’s Fantasia. For its finale, eight such balloons were left to float around the room while emitting breathing sounds, appearing like disembodied alien visitors. Soon after my return to Montreal, Marie Chouinard presented Henri Michaux : Mouvements. The genesis of this work, when Carol Prieur first incarnated the drawings of Henri Michaux back in 2005, is the reason why I’m a dance critic today. Seeing the twelve dancers of Chouinard’s company lend themselves to the exercise was just as riveting eight years later. By translating drawings into movement, Chouinard demonstrated the power of dance to think the body creatively. Usine C ended the year on a high note with their program from the Netherlands, most especially Ann Van den Broek’s feminist work for three female dancers, Co(te)lette. The show was powerful in its exposition of women’s bodies as a site of tension, torn between being objects of desire and embodied subjects. We can only hope that there will be more works like it in 2014.  TtBernadette, photo by Ernest Potters Enchanted Room, by Kristel van Issum & Guilherme Miotto “I feel like my heart’s going to explode!” The trees are bare. This is not an enchanted forest, but a room and, really, the enchanted part of it probably only exists in the characters’ head. Like the trunks without leaves around them, their bodies are strong, but their heads are weak. Their bodies are a joke played on them, athletic, but useless. Their pirouettes look ridiculous given that they’re barely holding it together otherwise. They’re delusional and the room in question might very well be a psych ward. Performer Oona Doherty looks like she’s channeling Saturday Night Live’s Molly Shannon’s most neurotic characters: Mary Katherine Gallagher, Sally O’Malley, Anna Nicole Smith, Courtney Love… She takes on a sexualized persona the façade of which she cannot maintain because too fragile, and it crumbles around her. “There is so much beauty in this world! I can’t take it in!” They may be quoting American Beauty, but the result is ironic. They’re not upper-middle class. They can’t just quit their job, work in a fast-food joint, and still buy the car of their dreams. They’re taking the piss out of it. That kind of beauty is also a privilege, one they will never be able to experience. TtBernadette, by Kristel van Issum TtBernadette shares a lot of similarities with Enchanted Room. The choreography is messy. Joss Carter and Doherty jump around, fall down, and spin without grace. They mostly function independently, but when they touch it’s harsh. As in the former, there are also costume and wig changes, like they’re sporting different personas, but it’s only an illusion; they don’t ever really change. It’s disheartening, leaving them and us with little hope. There is no escape. The washing machine in the middle of the stage highlights the lack of domesticity rather than its presence. The only thing domestic about their relationship is the sadomasochism that permeates it. All this to say that T.r.a.s.h. are so hardcore that they’re not for the faint of heart. I’m kidding. They really aren’t. March 5-9 at 8pm Danse Danse / Cinquième Salle www.dansedanse.net / laplacedesarts.com 514.842.2112 / 1.866.842.2112 Tickets: 40,71$ |

Sylvain Verstricht

has an MA in Film Studies and works in contemporary dance. His fiction has appeared in Headlight Anthology, Cactus Heart, and Birkensnake. s.verstricht [at] gmail [dot] com Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed