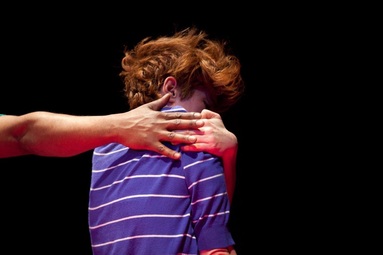

Quite Discontinuous, photo by Menno van der Meulen Quite Discontinuous, photo by Menno van der Meulen I didn’t watch Eurovision this weekend but I did go to Tangente to see Dance Roads, so let’s pretend that it’s the dance equivalent of Eurovision. In competition: Wales, the Netherlands, Canada, Italy, and France. Representing Wales, Jo Fong with Dialogue - A Double Act A video projection where the public sees itself in real-time, as in a mirror, which reminds me of the Belgian theatre company Ontroerend Goed’s Audience (and this even though I haven’t seen it). On stage, six chairs, two of which will find seaters, the female performers of Dialogue - A Double Act. They provide the suggestion of a performance, a sort of low-energy runthrough, like Michèle Febvre in Nicolas Cantin’s CHEESE. They often explain the performance instead of or just before actually doing it, like Andrew Turner had in Duet for One Plus Digressions. All this to say that it’s as charming as the performers are, but leaves us with a feeling of déjà-vu. Representing the Netherlands, Jasper van Luijk with Quite Discontinuous An athletic duo for two men with lots of floor work, which could make us think of breaking, but the moves are decidedly contemporary. The dancers are agile and the partner work is inventive. The relationship between the performers remains ambiguous. There seems to be a desire for connection, but both are on their own trajectory so that there is a difficulty in connecting. It might even be impossible. After one lies on the ground as though dead, the other shines spotlights on him, as an homage to the other and the desire for connection with him in spite of its unfeasibility. Representing Canada, Sarah Bronsard with Ce qui émerge après (4kg) A strange creature appears in obscurity at the back of the stage. We imagine there’s a dancer under there, though we can’t even figure out in what position they are. Soon we are able to make it out: it is her dress worn upside down, hanging off her body. She drops it on the floor, leaving her with a black pant-and-shirt combo. This is significant because Bronsard dances the flamenco but, like she leaves the typical dress behind, so she does with other elements of the dance. For example, she performs to ambient music and a dozen percussive contraptions with Mason jar lids for drums. As such, it’s hard to anticipate where the piece will go at any given moment, casting flamenco in a new light. Representing Italy, Andrea Gallo Rosso with I Meet You… If You Want Another duo for two men, which begins with them pushing each other’s back repeatedly, a rather lazy display of antagonism that unfortunately ends as soon as it gets more creative. In the second section, they evolve independently before falling into partner work for the third act. They end with the choreographic find of the piece as the two men, standing back to back, slide against each other to embrace on one side before sliding against each other’s back and embracing on the other side in a loop. Still, the piece lacks clarity. Representing France, Teilo Troncy with . je ne suis pas permanent . It begins quietly, with but a bit of a light on a sole woman. Soon, we hear music, but as though it is coming from a great distance. The dancer seems happy about it. The music comes in full force and she can finally do her jazzy dance with great energy. When the soundtrack disappears, she is left alone, humming as if trying to remember what she must do, psyching herself up. However, the grandeur of her movements danced to silence makes her look as though she’s having a meltdown. Things don’t seem to be going wrong technically as much as mentally. And the winner is… The Netherlands! Because it’s refreshing to see a contemporary dance piece that actually has dance in it. The Netherlands might seem like the obvious choice as it is the crowd-pleaser of the bunch. One might say that it’s not a particularly daring choice from the judges, but then again none of the pieces were especially daring either, so it might be fitting. www.danceroads.eu www.tangente.qc.ca

0 Comments

Levée des conflits, photo by Caroline Ablain Levée des conflits, photo by Caroline Ablain As my years as a dance critic pile on, it’s probably to be expected that I see more and more works I’ve already seen. This year, I can think of at least five off the top of my head. The one that most stood up to a repeat viewing was Matija Ferlin and Ame Henderson’s The Most Together We’ve Ever Been. I took the bus to Ottawa to see it just as a snowstorm was hitting the city. The ride ended up taking four hours. I barely had enough time to shove some of the worst food I’ve ever had in my mouth before running over to Arts Court, an old courthouse that has been turned into a beautiful art space. And, as soon as the show started, I knew it was all worth it. Back in Montreal, Israeli choreographer Sharon Eyal made a much-anticipated return after six years with Corps de Walk, a show she created with her partner Gai Behar. The uniformity she imposed on the twelve dancers of Norway’s Carte Blanche was oppressive and disturbing. It was its own indictment of homogeneity. At the Biennale de gigue contemporaine, the always reliable Nancy Gloutnez stood out yet again. With Les Mioles, she borrowed from classical music and became a conductor, turned her dancers’ feet into instruments, and composed a score reminiscent of Steve Reich in its obsessive build-up. After years of being one of the most rigorous emerging choreographers in Montreal, Sasha Kleinplatz has now fully emerged with Chorus II. The audience stood above six male dancers who swayed between demonstrations of physical strength and chill-inducing vulnerability. It is now up to venue artistic directors everywhere to shine on Kleinplatz the spotlight she so clearly deserves. Speaking of which, 2013 was the year of Agora de la danse. They probably had their best programming since I started following dance. It all began with Karine Denault’s Pleasure Dome, in which musicians and dancers explored pleasure without ever lazily resorting to shortcuts. Rather, she allowed the meaning of the work to emerge on its own and for Pleasure Dome to impose itself by the same token. It was followed by When We Were Old, a duo by Québec’s Emmanuel Jouthe and Italy’s Chiara Frigo (presented in collaboration with Tangente). The choreographer-dancers managed to bypass every single contemporary dance cliché that usually occurs as soon as a man and woman are onstage. In each and every moment, their encounter felt fresh and sincere. Agora ended the year with Prismes by Benoît Lachambre, who a month later would win the Montreal Dance Prize. Created for Montréal Danse, Prismes explored the effect of light on perception in a chromatic environment, as well as the fluidity of gender. Lighting designer Lucie Bazzo outdid herself for this highly experiential work. At the Festival TransAmériques, it was French choreographer Boris Charmatz who stood out with Levée des conflits, an opus of twenty-five movements repeated as a canon by twenty-four dancers. From the simplicity of the choreography to the high number of performers, Levée des conflits impressively hovered between minimalism and excess. I spent the summer in Iceland, where my trip ended with the Reykjavík Dance Festival. There, Norway’s Sissel M Bjørkli presented one of the most singular shows I’ve ever seen with Codename: Sailor V. It took place in a tiny space, barely big enough to seat fifteen. The smoke that filled the room along with Elisabeth Kjeldahl Nilsson and Evelina Dembacke’s intensely saturated coloured lighting blurred the edges of everything. Inspired by anime, Bjørkli created an alter ego for herself and through imaginative play managed to turn an office chair into a spaceship. That shit was magical. So was Nothing’s for Something by Belgium’s Heine Avdal and Yukiko Shinozaki, which opened with a ballet for six curtains, each suspended by six huge helium-filled balloons. Set to classical music, it was reminiscent of Disney’s Fantasia. For its finale, eight such balloons were left to float around the room while emitting breathing sounds, appearing like disembodied alien visitors. Soon after my return to Montreal, Marie Chouinard presented Henri Michaux : Mouvements. The genesis of this work, when Carol Prieur first incarnated the drawings of Henri Michaux back in 2005, is the reason why I’m a dance critic today. Seeing the twelve dancers of Chouinard’s company lend themselves to the exercise was just as riveting eight years later. By translating drawings into movement, Chouinard demonstrated the power of dance to think the body creatively. Usine C ended the year on a high note with their program from the Netherlands, most especially Ann Van den Broek’s feminist work for three female dancers, Co(te)lette. The show was powerful in its exposition of women’s bodies as a site of tension, torn between being objects of desire and embodied subjects. We can only hope that there will be more works like it in 2014.  When We Were Old, photo by Adrienne Surprenant When We Were Old, photo by Adrienne Surprenant “I bring you somewhere.” If you’re going to follow her, truly follow her, you need to trust her. Choreographers Chiara Frigo (Italy) and Emmanuel Jouthe (Québec) might hold hands with fingers interlaced, but it’s the only codified gesture you will find in When We Were Old. It is their starting point, a sign of trust and desire for true connection, from which anything can happen. Their relationship and the movements that stem from it are not predetermined. They are not playing roles. Their meeting is perpetual, occurs in each moment, like when they let go of each other, evolve independently, find each other again, and everything is to be done again. As a result, their meeting feels sincere. It also allows the performers to bypass all kinds of contemporary dance clichés that often emerge as soon as a woman and a man are onstage. Their duet is neither coupley, nor antagonistic. It just feels honest. It is no coincidence that, after the show, my date told me, “I liked that she was never weak.” Jouthe and Frigo are trying to build something together and, like the tree trunks they use as building blocks for her to stand on, the structure might end up making things shakier than no structure at all. And that’s okay. That’s the risk one takes in building a relationship or a dance. Even the Marley that covers the floor is loose, not taped down, and can be unrolled or rolled up, allowing change and surprise. Beneath, a new floor might be revealed, or even a new costume. It is as malleable as their relationship. Her movement is more spastic; his, more fluid and smooth. As they hover from side to side in opposite directions, they only ever meet for a brief moment in the middle. And that’s enough. By the end, it might even allow them to transform into dinosaurs among mountains made of chairs. It all depends on whether you trust them enough to bring you there. April 24-26 at 8pm Agora de la danse www.agoradanse.com / www.tangente.qc.ca 514.525.1500 Tickets: 28$ / Students or under 30: 20$ |

Sylvain Verstricht

has an MA in Film Studies and works in contemporary dance. His fiction has appeared in Headlight Anthology, Cactus Heart, and Birkensnake. s.verstricht [at] gmail [dot] com Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed