|

A month ago, I wrote that I go see dance because I love when people shut the fuck up. Yet last night I was ready to completely backtrack on this statement. It just goes to show that, with art, there is never any definite set of criteria that one can judge a work by, that art is chemistry that produces as many reactions as there are elements and audience members.

The occasion was Belgium-based American choreographer Meg Stuart’s unmissable return to Usine C with her solo Hunter. Her father was a community theatre director, she will tell us. As a result, she witnessed a lot of bad acting as a child, so she swore she’d never speak onstage. And for the first hour of this 90-minute show, she doesn’t. Treating her body as an archive of dance and memories, she moves in the style that has made her a contemporary dance icon. The collage aspect of the work is underlined incessantly, from the actual collage Stuart is making sitting at a table (and projected onto a screen at the back of the stage) at the beginning of the show to the sound collage by Vincent Malstaf and the video collage by Chris Kondek. I hear you loud and clear. It might be this aspect that most deters from the work. Like the soundtrack that moves through sound clips as though someone were switching through radio dials and never settling on any one channel, Stuart never sticks with anything for long, making us feel like we’re looking at a dancer improvising in the studio as she maintains a steady pace that comes across as manic. We want to tell her to calm down, to stand still for a moment. In her last show seen in Montreal, Built to Last, Stuart had touched on the ephemeral nature of dance by contextualizing it within a set that included a giant mobile of our solar system and mock-up of a T. rex skeleton. However, even though the set is also imposing in Hunter, it still replicates the blankness of the black box. In effect, it is like the table upon which Stuart does her collage: a rectangular blank surface on which beams are scattered around (like the pins used for her collage) from which rolls of fabric hang and are used as screens for the video projections. As a result, Stuart’s dance is decontextualized. What a welcomed change it is when she finally speaks. She maintains the stream of consciousness trope used throughout the show, but we do want to hear what she has to say about her life, about art, about anything. She’s Meg Stuart. She can speak onstage as much as she wants and we’ll listen. October 13-15 at 8pm www.agoradanse.com / www.usine-c.com 514.521.4493 Tickets: 38$ / Students or 30 years old and under: 30$

0 Comments

In this colourful dump, performers can disappear without leaving the stage or fall from considerable heights without hurting themselves. It is a post-apocalyptic world of overconsumption that lies before us and they are doomed to live in it. They may be able to choose from thousands of articles of clothing, but the choice is unappealing; it’s the only one they have. Their movement translates as play that spurs from idleness, which even comes across as the source of their masturbation and dry humping. They don’t even have the internet.

Every once in a while, unexpectedly, the performers cease their dicking around and break into beautiful song. In juxtaposing the music of Bach with a garbage dump, a thematic kinship emerges with Meg Stuart’s Built to Last (FTA, 2014): how is it possible that the species responsible for this post-apocalyptic mess also created such divine music? As the performers live out the last moments of life on earth in slow motion, we think there might be something redeeming about these creatures after all. May 29-June 1 Monument-National – Salle Ludger-Duvernay www.fta.qc.ca 514.844.3822 Tickets: 40-60$ 1. Tragédie, Olivier Dubois (Danse Danse)

Avec son opus pour dix-huit danseurs nus, Dubois a abordé les grands thèmes (le passage du temps, la mortalité, la petitesse de la vie humaine, le rôle de l’art, l’humanité) en prenant son temps, en n’empruntant aucun raccourci facile, en laissant le sens émerger de lui-même. 2. Uncanny Valley Stuff, Dana Michel (Usine C) Avec Uncanny Valley Stuff, Michel a continué sa recherche entamée avec Yellow Towel, spectacle qui figure dans le top dix du magazine new-yorkais Time Out et pour lequel le prestigieux festival ImPulsTanz a créé un prix spécialement pour elle. Sa nouvelle courte pièce est toute aussi incisive mais encore plus drôle. En empilant les clichés sur les Noirs jusqu’à ce qu’ils s’entremêlent et se contredisent, Michel démontre l’absurdité de ces stéréotypes qui nous présentent une vision déformée du monde. 3. Antigone Sr.: Twenty Looks or Paris Is Burning at the Judson Church (L), Trajal Harrell (Festival TransAmériques) Antigone Sr. a probablement été le spectacle de danse qui a créé le plus de divisions cette année. On pourrait diviser le public en trois : ceux qui ont quitté la salle, ceux qui sont restés assis les bras croisés, et ceux qui se sont levés pour danser. Il n’est donc pas surprenant que le spectacle se retrouve dans mon palmarès. Il faut dire que je suis queer et que j’ai une affinité pour la danse post-moderne, ce qui me donne une double porte d’entrée sur le sujet. Pour ceux qui n’ont pas eu l’endurance nécessaire pour passer à travers ce défilé de mode DIY de deux heures, il serait bon de noter que les plus grands bals qui ont inspiré la pièce pouvaient durer jusqu’à dix heures de temps; comptez-vous chanceux! Peut-être comprenez-vous maintenant un peu mieux ce que c’est que de se sentir aliéné par la culture dominante. 4. Monsters, Angels and Aliens Are Not a Substitute for Spirituality…, Andrew Tay (OFFTA) Pour être honnête, lorsque j’ai vu la nouvelle pièce de Tay, qui vire de plus en plus dans le performance art, je me suis demandé si j’étais en train de regarder un artiste perdre la tête sur scène ou si Tay était en contrôle de son art. J’étais évidemment assez intrigué pour découvrir la réponse avec Summoning Aesthetics qu’il a ensuite présenté avec François Lalumière au Festival Phénomena. Conclusion : Tay continue dans la même veine ritualiste, sachant clairement dans quelle direction il va même s’il ne connaît pas nécessairement sa destination. J’ai admiré qu’il ait pris la décision de terminer Monsters sur une note différente de ce qu’il avait prévu pendant la représentation même. La misogynie latente qui avait l’habitude d’hanter ses pièces est disparue. Ce qui demeure est son ludisme, son humour et son ouverture aux expériences, peu importe ce qu’elles s’avèrent être. Si je me souviens bien, un spectateur avait qualifié Summoning Aesthetics « d’honnêteté perverse. » Cela me semble aussi approprié. 5. Built to Last, Meg Stuart (Festival TransAmériques) Avec Built to Last, Stuart (qui a reçu le Grand Prix de la Danse de Montréal) a abordé des thèmes similaires à ceux de Tragédie d’Olivier Dubois, mais de façon beaucoup plus théâtrale. En juxtaposant un immense mobile de notre système solaire avec une maquette d’un tyrannosaure et la danse contemporaine avec la musique classique, Stuart a démontré l’insignifiance des actions humaines et que notre seule rédemption possible se trouve dans l’art. 6. Florilège, Margie Gillis (Agora de la danse) Pour célébrer ses quarante ans de carrière, Gillis nous a offert cinq pièces de son répertoire revisitant les années 1978 à 1997. Par le fait même, elle nous a rappelé pourquoi elle est devenue une danseuse de telle renommée. L’intangible se manifeste à travers son corps, soulignant la fragilité de l’humain dans un univers chaotique. 7. Mange-moi, Andréane Leclerc (Tangente) Leclerc a utilisé la contorsion et la nudité pour aborder les relations de pouvoir entre les individus lorsque notre survie dépend des autres. Qu’elle puisse s’attaquer à de telles questions tout en offrant une des pièces les plus sensorielles de l’année démontre l’intelligence de son travail. 8. Tête-à-Tête, Stéphane Gladyszewski (Agora de la danse) Ma réaction à ma sortie de cette pièce de quinze minutes pour un seul spectateur à la fois : on doit donner à Gladyszewski tout l’argent dont il a besoin pour réaliser ses projets. Aucun autre chorégraphe n’arrive à intégrer la technologie avec autant d’adresse. Tête-à-Tête était à la fois intime, inquiétant et magique. 9. The Nutcracker, Maria Kefirova (Tangente) L’excentrique Kefirova a troqué l’écran vidéo pour des haut-parleurs et a démontré qu’elle maîtrise le son avec autant de flair que l’image. « Elle n’utilise pas le son pour meubler le silence comme le fond maints spectacles, mais pour matérialiser l’invisible, » disais-je. Difficile d’oublier la satisfaction ressentie lors de l’exutoire du tableau final, où Kefirova s’acharne à faire éclater des noix de Grenoble en morceaux en se servant de ses chaussures à talons hauts comme casse-noisette. 10. Junkyard/Paradis remix, Catherine Vidal (Usine C) J’espère avoir assez établi le fait que je suis un fan fini de Mélanie Demers pour pouvoir dire ceci (qui, je crois, n’est pas l’opinion populaire) : Junkyard/Paradis est probablement sa pièce que j’aime le moins. Lors de l’événement MAYDAY remix, où la chorégraphe a laissé des artistes remixer son travail, la metteure en scène Catherine Vidal a donné au spectacle la structure dramatique qu’il méritait avec une fin des plus jubilatoires. 11. loveloss, Michael Trent (Agora de la danse) Extrait de ma critique : « Trent n’a toujours pas peur de prendre le temps qu’il faut. De plus, il évite ici l’humour, le théâtral et le mouvement séducteur (athlétique, rapide, synchronisé), toutes ces astuces que des chorégraphes moins confiants utilisent pour que leur dance soit plus accessible. L’interprétation est sentie sans être affectée. loveloss est une œuvre touchante … » 12. Milieu de nulle part, Jean-Sébastien Lourdais (Agora de la danse) Pour la performance de l’année, celle de Sophie Corriveau, qui s’est méritée la toute première résidence de création pour interprètes offerte par l’Agora de la danse. Notons que le diffuseur s’est démarqué avec une programmation solide pour une deuxième année consécutive.  Germinal, photo d'Alain Rico Germinal, photo d'Alain Rico Germinal d’Antoine Defoort et Halory Goerger, c’est du théâtre qui ne prend rien pour acquis, incluant le théâtre. C’est donc une genèse de la scène qui débute dans le noir et qui, comme l’autre genèse, doit d’abord faire appel à la lumière pour révéler ce monde. Outre les parallèles avec le récit biblique de la création, Germinal joue avec l’histoire de l’humanité. C’est donc ainsi que le mot écrit, projeté sur le mur du fond, précède inexplicablement la parole. Les quatre interprètes en viennent à se servir des surtitres pour dresser une liste de leurs découvertes scéniques et des concepts qui en découlent. C’est la boîte de Pandore qui s’ouvre et les concepts s’enchaînent et se multiplient jusqu’à ce qu’on n’arrive plus à y voir clair. C’est alors que les interprètes ont cette autre idée très humaine, celle de créer des catégories pour démêler tout ça. Influencés par les éléments limités à leur disposition et la découverte d’un micro sous la scène, ils décident de diviser les éléments entre ceux qui font « pocpoc » au contact avec le micro et ceux qui ne font « pas pocpoc. » Émergent alors l’absurdité de l’aspect arbitraire de la catégorisation, l’ironie qui en ressort lorsqu’on découvre que l’idée du pocpoc ne fait pas pocpoc, et la métaphore alors qu’on se rend compte que quelque chose peut faire « pocpoc dans le cœur. » En répartissant leur énumération sur une ligne chronologique, ils en viennent au moment présent, au-delà duquel l’inconnu règne. Toutefois, ils entrevoient le mot « fin » avant de rapidement rebrousser chemin. Évidemment, il est question de la fin de la pièce, mais aussi celle de la vie. Les interprètes passent donc à travers les étapes du deuil avant que Beatriz Setien, en mode acceptation/reconstruction, déclare « Je propose qu’on fasse un truc bien. » C’est alors qu’ils créent une chanson à partir de la liste de mots qu’ils ont débité tout au long du spectacle. Encore une fois – je pense à Built to Last de Meg Stuart, vu le soir précédent, et Tragédie d’Olivier Dubois – l’art est présenté comme étant la réponse appropriée face à la mortalité, la seule rédemption possible. Alors que les mots s’accumulent, on peut penser au livre-poème Alphabet d’Inger Christensen, ode à l’abondance de la vie. En passant de rien à tout, Germinal peut aussi nous rappeler le film Nothing du Canadien Vincenzo Natali, si on le faisait jouer en sens inverse. Germinal baigne dans l’humour. Les blagues sont souvent évidentes et étirées au-delà de leur élasticité. C’est un spectacle qui se veut plaisant et séducteur; et, soir de première montréalaise, il a visiblement plu à un public séduit. Personnellement, ça m’a fait apprécier de plus belle Built to Last, moins racoleur, plus admirable. 29 & 30 mai à 20h / 31 mai & 1er juin à 16h Maison Théâtre www.fta.qc.ca 514.844.3822 / 514.842.2112 Billets : 43$ / 30 ans et moins ou 65 ans et plus : 38$  Built to Last, photo d'Eva Wurdinger Built to Last, photo d'Eva Wurdinger Lorsque j’ai assisté au concert de Martha Wainwright au Théâtre Outremont, je ne pouvais cesser de percevoir l’événement tel qu’il était. Assis au balcon, j’étais étrangement conscient du fait que nous étions sur une gigantesque boule qui flottait dans l’espace, boule sur laquelle un bâtiment avait été érigé, bâtiment dans lequel un être humain chantait, être humain qui était observé par une centaine d’autres de son espèce. Tout ça me semblait d’une absurdité et d’une beauté totales. Cette absurdité n’est pas seulement le contexte inévitable de Built to Last de Meg Stuart, mais aussi son contenu. Au-dessus de la scène est suspendu un mobile géant de neuf planètes entourant un soleil blanc. En avant-scène git une maquette de tyrannosaure. La scène, microcosme pour la planète terre au complet, apparait comme un terrain de jeu immense où les actions humaines n’ont rien à voir avec les forces de l’univers. L’insignifiance des humains transparaît. Ils ne font que jouer; ils n’ont jamais la chance de participer aux affaires de l’univers ou même de les influencer le moindrement. La danse initiale des cinq interprètes se limite à un calcul de l’espace, aux paramètres du corps qu’ils ne peuvent jamais excéder. Ils sont confinés à l’humain. Alors, sur ce terrain de jeu démesuré, les danseurs (mais aussi les personnages qu’ils interprètent) font du théâtre. Leurs mouvements ne s’accumulent pas; ils ne font que se suivre et ils perdent leur sens aussitôt qu’ils sont exécutés. « Nous sommes motivés par l’enthousiasme, » dit l’un des interprètes. L’enthousiasme… Un sentiment vif, mais qui ne sait perdurer. « What’s in our hearts and in our souls must find a way out. » Built to Last avance au son de Stockhausen, de Beethoven, de Rachmaninov… Il y a un décalage énorme entre ces musiques dramatiques et la danse des interprètes, qui ne font pas dans la virtuosité. Ironiquement, la musique semble plus appropriée pour le mouvement des planètes que celui des humains. Notre musique est plus grande que nous. Peut-être est-ce pour cela que la musique de Beethoven aura survécu plus longtemps que Beethoven lui-même. Elle n’est pas du domaine de l’humain, mais du divin. Dans un cube blanc, les danseurs bougent comme s’ils se trouvaient en état d’apesanteur. Les quelques moments magiques offerts par Built to Last ne semblent pas parvenir de l’intérieur de l’humain, mais de sa place dans l’univers. Je le répète : nous nous trouvons sur une boule qui flotte dans l’espace. Dans Forgeries, Love and Other Matters, œuvre co-créée avec Benoît Lachambre, Stuart nous avait présenté un monde post-apocalyptique. À la manière de Charlton Heston devant la Statue de la Liberté dans Planet of the Apes, avec Built to Last, on se rend compte que ce monde est peut-être déjà le nôtre. Tout dépendant d’où notre regard se pose, le titre du spectacle peut paraître ironique ou approprié. Les planètes sont faites pour durer. Le dinosaure, non. Les humains… Ils sont des dinosaures en devenir. Nous ne sommes que de futurs fossiles. 28 & 29 mai à 20h Usine C www.fta.qc.ca 514.844.3822 / 514.842.2112 Billets : 48$ / 30 ans et mois ou 65 ans et plus : 43$  Levée des conflits, photo by Caroline Ablain Levée des conflits, photo by Caroline Ablain As my years as a dance critic pile on, it’s probably to be expected that I see more and more works I’ve already seen. This year, I can think of at least five off the top of my head. The one that most stood up to a repeat viewing was Matija Ferlin and Ame Henderson’s The Most Together We’ve Ever Been. I took the bus to Ottawa to see it just as a snowstorm was hitting the city. The ride ended up taking four hours. I barely had enough time to shove some of the worst food I’ve ever had in my mouth before running over to Arts Court, an old courthouse that has been turned into a beautiful art space. And, as soon as the show started, I knew it was all worth it. Back in Montreal, Israeli choreographer Sharon Eyal made a much-anticipated return after six years with Corps de Walk, a show she created with her partner Gai Behar. The uniformity she imposed on the twelve dancers of Norway’s Carte Blanche was oppressive and disturbing. It was its own indictment of homogeneity. At the Biennale de gigue contemporaine, the always reliable Nancy Gloutnez stood out yet again. With Les Mioles, she borrowed from classical music and became a conductor, turned her dancers’ feet into instruments, and composed a score reminiscent of Steve Reich in its obsessive build-up. After years of being one of the most rigorous emerging choreographers in Montreal, Sasha Kleinplatz has now fully emerged with Chorus II. The audience stood above six male dancers who swayed between demonstrations of physical strength and chill-inducing vulnerability. It is now up to venue artistic directors everywhere to shine on Kleinplatz the spotlight she so clearly deserves. Speaking of which, 2013 was the year of Agora de la danse. They probably had their best programming since I started following dance. It all began with Karine Denault’s Pleasure Dome, in which musicians and dancers explored pleasure without ever lazily resorting to shortcuts. Rather, she allowed the meaning of the work to emerge on its own and for Pleasure Dome to impose itself by the same token. It was followed by When We Were Old, a duo by Québec’s Emmanuel Jouthe and Italy’s Chiara Frigo (presented in collaboration with Tangente). The choreographer-dancers managed to bypass every single contemporary dance cliché that usually occurs as soon as a man and woman are onstage. In each and every moment, their encounter felt fresh and sincere. Agora ended the year with Prismes by Benoît Lachambre, who a month later would win the Montreal Dance Prize. Created for Montréal Danse, Prismes explored the effect of light on perception in a chromatic environment, as well as the fluidity of gender. Lighting designer Lucie Bazzo outdid herself for this highly experiential work. At the Festival TransAmériques, it was French choreographer Boris Charmatz who stood out with Levée des conflits, an opus of twenty-five movements repeated as a canon by twenty-four dancers. From the simplicity of the choreography to the high number of performers, Levée des conflits impressively hovered between minimalism and excess. I spent the summer in Iceland, where my trip ended with the Reykjavík Dance Festival. There, Norway’s Sissel M Bjørkli presented one of the most singular shows I’ve ever seen with Codename: Sailor V. It took place in a tiny space, barely big enough to seat fifteen. The smoke that filled the room along with Elisabeth Kjeldahl Nilsson and Evelina Dembacke’s intensely saturated coloured lighting blurred the edges of everything. Inspired by anime, Bjørkli created an alter ego for herself and through imaginative play managed to turn an office chair into a spaceship. That shit was magical. So was Nothing’s for Something by Belgium’s Heine Avdal and Yukiko Shinozaki, which opened with a ballet for six curtains, each suspended by six huge helium-filled balloons. Set to classical music, it was reminiscent of Disney’s Fantasia. For its finale, eight such balloons were left to float around the room while emitting breathing sounds, appearing like disembodied alien visitors. Soon after my return to Montreal, Marie Chouinard presented Henri Michaux : Mouvements. The genesis of this work, when Carol Prieur first incarnated the drawings of Henri Michaux back in 2005, is the reason why I’m a dance critic today. Seeing the twelve dancers of Chouinard’s company lend themselves to the exercise was just as riveting eight years later. By translating drawings into movement, Chouinard demonstrated the power of dance to think the body creatively. Usine C ended the year on a high note with their program from the Netherlands, most especially Ann Van den Broek’s feminist work for three female dancers, Co(te)lette. The show was powerful in its exposition of women’s bodies as a site of tension, torn between being objects of desire and embodied subjects. We can only hope that there will be more works like it in 2014. My wish for the Montreal dance scene in 2013 is for Marie-Hélène Falcon to quit her job as artistic director of the Festival TransAmériques. I’m hoping she’ll become the director of a theatre so that the most memorable shows will be spread more evenly throughout the year instead of being all bunched up together in a few weeks at the end of spring. With that being said, here are the ten works that still resonated with me as 2012 came to an end. 1. Cesena, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker + Björn Schmelzer (Festival TransAmériques)

I’ve been thinking about utopias a lot this year. I’ve come to the conclusion that – since one man’s utopia is another’s dystopia – they can only be small in nature: one person or, if one is lucky, maybe two. With Cesena, Belgian choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker showed me that it could be done with as many as nineteen people, if only for two hours, if only in a space as big as a stage. Dancers and singers all danced and sang, independently of their presupposed roles, and sacrificed the ego’s strive for perfection for something better: the beauty of being in all its humanly imperfect manifestations. They supported each other (even more spiritually than physically) when they needed to and allowed each other the space to be individuals when a soul needed to speak itself. 2. Sideways Rain, Guilherme Botelho (Festival TransAmériques) I often speak of full commitment to one’s artistic ambitions as extrapolated from a clear and precise concept carried out to its own end. Nowhere was this more visible this year than in Botelho’s Sideways Rain, a show for which fourteen dancers (most) always moved from stage left to stage right in a never-ending loop of forward motion. More than a mere exercise, the choreography veered into the metaphorical, highlighting both the perpetual motion and ephemeral nature of human life, without forgetting the trace it inevitably leaves behind, even in that which is most inanimate. More importantly, it left an unusual trace in the body of the audience too, making it hard to even walk after the show. 3. (M)IMOSA: Twenty Looks or Paris Is Burning at the Judson Church (M), Cecilia Bengolea + François Chaignaud + Trajal Harrell + Marlene Monteiro Freitas (Festival TransAmériques) By mixing post-modern dance with queer performance, the four choreographer-dancers of (M)IMOSA offered a show that refreshingly flipped the bird to the usual conventions of the theatre. Instead of demanding silence and attention, they left all the house lights on and would even walk in the aisles during the show, looking for their accessories between or underneath audience members. Swaying between all-eyes-on-me performance and dancing without even really trying, as if they were alone in their bedroom, they showed that sometimes the best way to dramatize the space is by rejecting the sanctity of theatre altogether. 4. Goodbye, Mélanie Demers (Festival TransAmériques) Every time I think about Demers’s Goodbye (and it’s quite often), it’s always in conjunction with David Lynch’s Inland Empire. The two have a different feel, for sure, but they also do something quite similar. In Inland Empire, at times, an actor will perform an emotional scene, and Lynch will then reveal a camera filming them, as if to say, “It’s just a movie.” Similarly, in Goodbye, dancer Jacques Poulin-Denis can very well say, “This is not the show,” it still doesn’t prevent the audience from experiencing affect. Both works show the triviality of the concept of suspension of disbelief, that art does not affect us in spite of its artificiality, but because of it. 5. The Parcel Project, Jody Hegel + Jana Jevtovic (Usine C) One of the most satisfying days of dance I’ve had all year came as a bit of a surprise. Five young choreographers presented the result of their work after but a few weeks of residencies at Usine C. I caught three of the four works, all more invigorating than some of the excessively polished shows that some choreographers spend years on. It showed how much Montreal needs a venue for choreographers to experiment rather than just offer them a window once their work has been anesthetically packaged. The most memorable for me remains Hegel & Jevtovic’s The Parcel Project, which began with a surprisingly dynamic and humorous 20-minute lecture. The second half was an improvised dance performance, set to an arbitrarily selected pop record, which ended when the album was over, 34 minutes later. It was as if John Cage had decided to do dance instead of music. Despite its explanatory opening lecture, The Parcel Project was as hermetic as it was fascinating. 6. Spin, Rebecca Halls (Tangente) Halls took her hoop dancing to such a degree that she exceeded the obsession of the whirling dervish that was included in the same program as her, and carried it out to its inevitable end: exhaustion. 7. Untitled Conscious Project, Andrew Tay (Usine C) Also part of the residencies at Usine C, Tay produced some of his most mature work to date, without ever sacrificing his playfulness. 8. 1001/train/flower/night, Sarah Chase (Agora de la danse) Always, forever, Sarah Chase, the most charming choreographer in Canada, finding the most unlikely links between performers. She manages to make her “I have to take three boats to get to the island where I live in BC” and her “my dance studio is the beach in front of my house” spirit emerge even in the middle of the city. 9. Dark Sea, Dorian Nuskind-Oder + Simon Grenier-Poirier (Wants & Needs Danse/Studio 303) Choreographer Nuskind-Oder and her partner-in-crime Grenier-Poirier always manage to create everyday magic with simple means, orchestrating works that are as lovely as they are visually arresting. 10. Hora, Ohad Naharin (Danse Danse) A modern décor. The legs of classical ballet and the upper body of post-modern dance, synthesized by the athletic bodies of the performers of Batsheva. These clear constraints were able to give a coherent shape to Hora, one of Naharin’s most abstract works to date. Scrooge Moment of the Year Kiss & Cry, Michèle Anne De Mey + Jaco Van Dormael (Usine C) Speaking of excessively polished shows… La Presse, CIBL, Nightlife, Le Devoir, and everyone else seemingly loved Kiss & Cry. Everyone except me. To me, it felt like a block of butter dipped in sugar, deep fried, and served with an excessive dose of table syrup; not so much sweet as nauseating. It proved that there’s no point in having great means if you have nothing great to say. Cinema quickly ruined itself as an art form; now it apparently set out to ruin dance too. And I’m telling you this so that, if Kiss & Cry left you feeling dead on the inside, you’ll know you’re not alone.  Sharon Eyal & Gai Bachar’s Corps de Walk, photo by Erik Berg Sharon Eyal & Gai Bachar’s Corps de Walk, photo by Erik Berg Benoît Lachambre’s Snakeskins: because you can only accuse Lachambre of being so hit-or-miss due to his uncompromising commitment to his artistic pursuits… and he’s due for a hit. (October 10-12, Usine C) Nicolas Cantin’s Grand singe: because nobody else manages to pack as much punch by doing so little. (October 30-November 1, Usine C) Brian Brooks’s Big City & Motor: because Brooks explores concepts that only push his choreography further into the physical world, turning the human body into little more than a machine. (November 22-25, Tangente) Karine Denault’s PLEASURE DOME: because we haven’t seen her work since 2007, when she presented the intimate Not I & Others using only half of the small Tangente space, dancing with humility, as though the line between performer and spectator simply hinged on a matter of perspective. (February 6-9, Agora de la danse) Pieter Ampe & Guilherme Garrido’s Still Standing You: because Ampe & Garrido have created one of the most compelling shows of the past few years, a dense study of masculinity and friendship covered with a thick layer of Jackass trash. (February 12-16, La Chapelle) Sharon Eyal & Gai Bachar’s Corps de Walk: because it’s the first time we get to see a work by Eyal in six years, when she blew us away with a non-stop human parade that was decidedly contemporary in its transnationalism and use of everyday movements like talking on cell phones. (February 28-March 2, Danse Danse) Mélanie Demers’s Goodbye: because, much like David Lynch did with Inland Empire, Demers demonstrated that an artist doesn’t need to instill suspension of disbelief in its audience to work, that dance can be powerful as dance just as film can be powerful as film. (March 20-22, Usine C) Maïgwenn Desbois’s Six pieds sur terre: because Desbois demonstrated that one doesn’t need to sacrifice art in order to make integrated dance. (March 21-24, Tangente) Yaëlle & Noémie Azoulay’s Haute Tension: because Yaëlle Azoulay came up with the most exclamative piece ever presented at the Biennales de Gigue Contemporaine. (March 28-30, Tangente) Dorian Nuskind-Oder’s Pale Water: because with simple means Nuskind-Oder manages to create everyday magic. (May 10-12, Tangente)  Cesena, photo d'Anne Van Aerschot Cesena, photo d'Anne Van Aerschot L’impression que Cesena – le spectacle de près de deux heures da la chorégraphe belge Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker – laisse pourrait être traître. Je ne peux qu’y penser comme une utopie. Pourtant, si je m’efforce, je dois me rappeler que les premières 30-40 minutes sont exigeantes. Une seule lumière éclaire à peine la scène, de sorte que l’action est pratiquement invisible même lorsqu’elle est excessivement dynamique. Les interprètes sont alors moins corps que contours, moins physiques qu’audibles. La scène est parsemée de sable formant un large cercle et, typique pour De Keersmaeker, les pieds des interprètes trainent sur le sol. Pied contre sable, sable contre sol. Plancher sablé. Les interprètes ne volent pas, ne flottent pas. Leur danse est bien ancrée dans le poids indéniable du corps qui les humanise. Ils sont dix-neuf en tout, certains danseurs, certains chanteurs, sans toujours qu’on puisse les différencier, même si on peut souvent le deviner. C’est que tous les interprètes s’adonnent autant à la danse qu’au chant. Pour cette dernière, on retourne au quatorzième siècle avec l’ars subtilior, ici dirigé par Björn Schmelzer. Le peu que l’on aperçoit nous laisse déjà entrevoir la communauté. Les mains des uns reposent sur les épaules des autres alors qu’ils se déplacent à l’unisson. Une note, un pas. Silence, immobilité. La danse et le chant deviennent indissociables. Après tout, ils émanent tous deux du mouvement. Et une deuxième lumière. Ce n’est qu’à ce moment qu’on découvre le genre, qui se trouve être hors du commun pour un spectacle de danse contemporaine. Seize hommes et seulement trois femmes. Et une troisième lumière. J’ai parlé d’utopie parce qu’il y a ici une parfaite balance entre la communauté et l’individu. Les interprètes se supportent, souvent plus moralement que physiquement, mais aussi s’effacent vers les côtés de la scène lorsqu’ils doivent laisser de la place aux individus qui se démènent dans l’extase. On retrouve aussi cette dualité dans les costumes. Leurs chandails, pantalons et robes sont tous foncés, clairement le fruit d’une coordination esthétique. Par contre, aux pieds, on devine de par l’éclectisme coloré qu’on y trouve que chacun porte ses espadrilles préférées. Vers la fin du spectacle, certains échangeront leur sombre chandail pour un plus coloré. Je parle aussi d’utopie à cause de l’effacement des rôles prédéterminés qui permet à tous les interprètes de s’adonner à la danse et au chant. Oui, on peut deviner que certains sont plus danseur que chanteur (et vice versa), mais ce n’est pas perçu comme étant « meilleur » ou « pire. » Ce sont tout simplement différentes qualités de mouvement et de voix qui émergent. Ils sont tous beaux. Cesena 1-2 juin à 20h Théâtre Maisonneuve www.fta.qc.ca 514.844.3822 / 1.866.984.3822 Billets à partir de 35$  Still Standing You, photo by Phile Deprez Still Standing You, photo by Phile Deprez Have you ever wondered what Jackass would look like if it were contemporary dance instead of performance art? Me neither, yet last night I got to find out all the same. With Still Standing You, Belgian Pieter Ampe and Portuguese Guilherme Garrido have produced the kind of work that can only come from a place of deep friendship and trust. How else could a couple of straight buds hold each other’s sweaty cock? From the beginning, they are pushing their bodies to the limit as Ampe is lying on the floor, legs straight in the air, and Garrido sits on his feet while making casual conversation with the audience. As is often the case, the job is harder for Ampe, and Guilherme likes to be a dick about it. When he moves his feet to Ampe’s hands, he then puts his own hands on Ampe’s still erect feet, then his fists, then but a finger to show how easy his end of the deal is. They grunt like cave men as they lift and rock each other as though fucking… before the one standing up forcefully throws the other on the ground. Riding on each other’s back, they act like Godzilla destroying the helpless tiny city below them. But play, just like sex, can on a dime turn brutal. Ampe stands on Garrido’s lying body and walks on top of him by lifting him by the belt and shirt. There is no music (except for the percussive one they create with their bodies) and all the stage lights are on for the length of the show. While for most shows it is better to hide as much as possible to stimulate the imagination, here everything must be seen. Still Standing You is not trying to be pretty or graceful. When a move threatens to become so, the men simply drop each other on the ground. It’s about making it look hard rather than easy. Still Standing You is a mix of physical feats (how to move around one another while holding each other’s penis?), slapstick, competitive play, juvenile behaviour, male bonding, circus acts, and sadomasochism. Both performers and audience members participate in the latter. However, moments of genuine care can also be witnessed, like when one massages the ass of his partner… before pushing him down the floor with his feet. After all, S&M isn’t about hurting the other with malignant intent; it’s about caring enough about the other to be able to fulfil their desire to experience pain. The men also rest on top of each other, gently blow on each other, carry each other in their arms, and arrange each other’s pubic hair. It’s the kind of love that makes it possible to hit each other with a belt and still be okay with one another. After the show, I heard someone say “C’est con, mais c’est bon.” Yes, it is bon. More than bon, actually. But con it certainly isn’t. If anything, Still Standing You is one of the densest shows I have ever seen. Someone could write a PhD thesis about it (and undoubtedly will). It’s about man with a small “m” as beast. It’s about the non-existent line between male bonding behaviour and homoeroticism. It takes the piss out of contemporary dance. It’s a parody of gender performance, of machismo. It’s camp. Who else can claim to have managed to perform drag while completely naked? It’s quite simply the most riveting show I’ve seen in years. Still Standing You June 1-3 at 9pm Théâtre La Chapelle www.fta.qc.ca 514.844.3822 Tickets: 28$ / Under 31, over 64 years old: 22$ |

Sylvain Verstricht

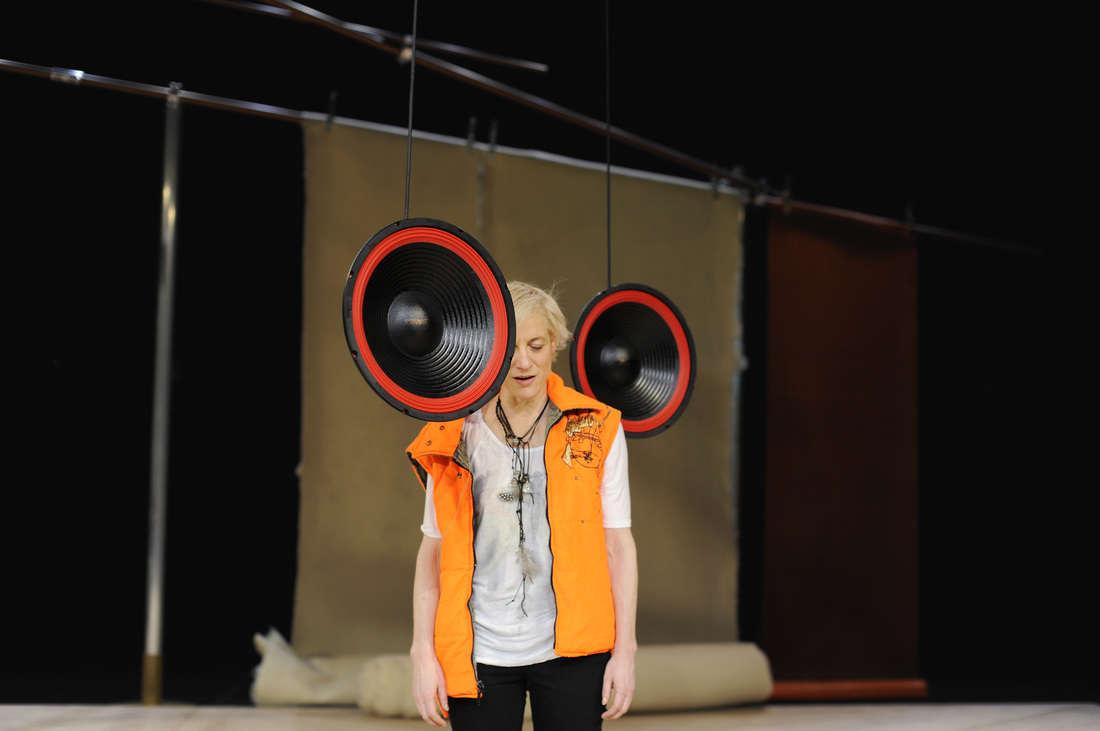

has an MA in Film Studies and works in contemporary dance. His fiction has appeared in Headlight Anthology, Cactus Heart, and Birkensnake. s.verstricht [at] gmail [dot] com Categories

All

|

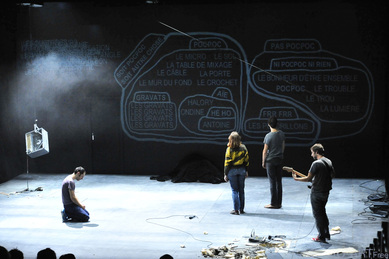

RSS Feed

RSS Feed