|

1. Judson Church is Ringing in Harlem (Made-to-Measure) / Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at the Judson Church (M2M), Trajal Harrell + Thibault Lac + Ondrej Vidlar (Festival TransAmériques) American choreographer Trajal Harrell’s work has always been impressive if only for its sheer ambition (his Twenty Looks series currently comprises half a dozen shows), but Judson Church is Ringing in Harlem (Made-to-Measure) is his masterpiece. In the most primal way, he proves that art isn’t a caprice but that it is a matter of survival. Harrell and dancers Thibault Lac and Ondrej Vidlar manifest this need by embodying it to the fullest. The most essential show of this or any other year. 2. ENTRE & La Loba (Danse-Cité) & INDEEP, Aurélie Pedron Locally, it was the year of Aurélie Pedron. She kept presenting her resolutely intimate solo ENTRE, a piece for one spectator at a time who – eyes covered – experiences the dance by touching the performer’s body. In the spring, she offered a quiet yet surprisingly moving 10-hour performance in which ten blindfolded youths who struggled with addiction evolved in a closed room. In the fall, she made us discover new spaces by taking over Montreal’s old institute for the deaf and mute, filling its now vacant rooms with a dozen installations that ingeniously blurred the line between performance and the visual arts. Pedron has undeniably found her voice and is on a hot streak. 3. Co.Venture, Brooklyn Touring Outfit (Wildside Festival) The most touching show I saw this year, a beautiful portrait of an intergenerational friendship and of the ways age restricts our movement and dance expands it. 4. Avant les gens mouraient (excerpt), Arthur Harel & (LA)HORDE (Marine Brutti, Jonathan Debrouwer, Céline Signoret) (Festival TransAmériques) wants&needs danse’s The Total Space Party allowed the students of L’École de danse contemporaine to revisit Avant les gens mouraient. It made me regret I hadn’t included it in my best of 2014 list, so I’m making up for it here. Maybe it gained in power by being performed in the middle of a crowd instead of on a stage. Either way, this exploration of Mainstream Hardcore remains the best theatrical transposition of a communal dance I’ve had the chance to see. 5. A Tribe Called Red @ Théâtre Corona (I Love Neon, evenko & Greenland Productions) I’ve been conscious of the genocide inflicted upon the First Nations for some time, but it hit me like never before at A Tribe Called Red’s show. I realized that, as a 35 year-old Canadian, it was the first time I witnessed First Nations’ (not so) traditional dances live. This makes A Tribe Called Red’s shows all the more important. 6. Naked Ladies, Thea Fitz-James (Festival St-Ambroise Fringe) Fitz-James gave an introductory lecture on naked ladies in art history while in the nude herself. Before doing so, she took the time to look each audience member in the eye. What followed was a clever, humorous, and touching interweaving of personal and art histories that exposed how nudity is used to conceal just as much as to reveal. 7. Max-Otto Fauteux’s scenography for La très excellente et lamentable tragédie de Roméo et Juliette (Usine C)

Choreographer Catherine Gaudet and director Jérémie Niel stretched the short duo they had created for a hotel room in La 2e Porte à Gauche’s 2050 Mansfield – Rendez-vous à l’hôtel into a full-length show. What was most impressive was scenographer Max-Otto Fauteux going above and beyond by recreating the hotel room in which the piece originally took place, right down to the functioning shower. The surreal experience of sitting within these four hyper-realistic walls made the performance itself barely matter.

1 Comment

C’est un spectacle. I don’t know why anyone would expect anything else when going to Place des Arts to witness Nederlands Dans Theater passing through Montreal for the first time in over twenty years. For the occasion, we were treated to a Crystal Pite sandwich on Sol León & Paul Lightfoot bread. Sehnsucht opens and ends with a man bowing in a frog-like position at the front of the stage. In the background, a straight couple engages in a pas de deux in a cubic room. Like the needles of a clock, their legs and arms stretch out and rotate around a two-dimensional axis. Their movement is fast-paced while that of the man in the foreground is fluid but sculptural in its slowness and poses, as though time passed more slowly for those alone. The room spins vertically, so that the dancers sometimes appear to defy gravity like Fred Astaire in Royal Wedding, sitting on a chair that hangs from a wall, for example. The choreographers use this magical element to charm the public without pushing it to the point where it would transcend its gimmick. The room disappears and thirteen dancers come out for the middle section. They dance synchronously in a manner that is reminiscent of Ohad Naharin’s Hora: the athletic bodies of the dancer maintain the legs of ballet (pirouettes included); however, while the upper bodies in Hora could be said to fall under a post-modern aesthetic, here they are more akin to music video choreography. (The synchronicity might partially be to blame for this.) The fast pace of the choreography follows along the gaudiness of Beethoven’s Symphony Nr. 5, resulting in the kind of comic effect that the Looney Tunes capitalized on.

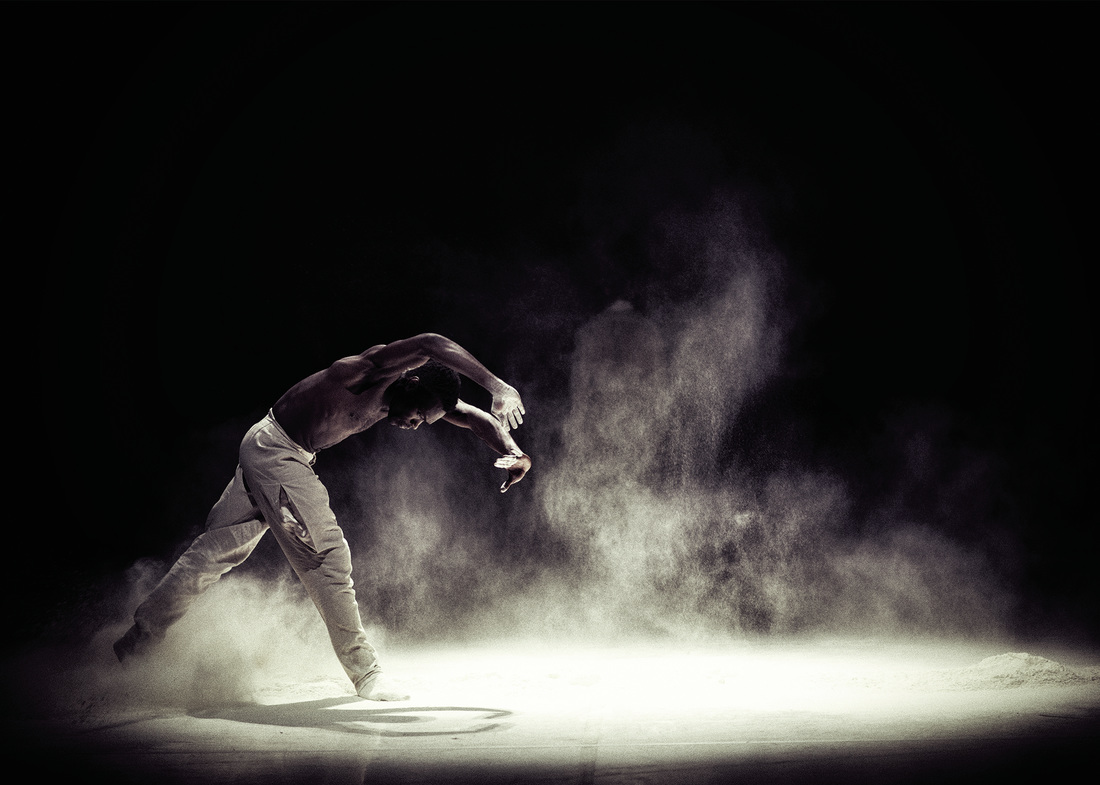

Canadian choreographer Pite offers the strongest piece of this triple bill with In the Event. Set against a grey sandy backdrop, eight dancers appear like a group on an expedition through the darkness of a foreign planet. The world around them feels potentially threatening, from their shadows moving along the walls of a cave to the rumbling on the soundtrack and the lightning that shatters the background. However, the dancers are in it together, cooperating as a group, sometimes literally forming a human chain with their limbs. The movement is elastic, round, and refreshingly ungendered. The dancers slide against the floor, sometimes even float above it. A solo provides the piece with a dramatic ending as a man’s hands frantically search the floor and reach for his chest and throat as if he were choking. For Pite, being alone looks like being lost. León & Lightfoot fare better with Stop-Motion, a piece for seven dancers that is gothic-looking with its black background, white and beige pants, white walls, floor and powder, and black and white video projection. The dance is better served by Max Richter’s moody modern classical music. In solos and duos, the agility of the dancers is used to evoke emotion rather than being an end in and of itself like in Sehnsucht. However, the choreographers once again go for synchronicity for the group section; rather than intensifying the effect, it comes across as lazy and dilutes it. As the piece ends, some curtains are lowered while others after are lifted, and the lighting grid also comes down. There is the feeling that León & Lightfoot are doing this just because they can. With this triple bill, they show that they have the dancers and the means to make great art, but they fail to prove that they have the will. November 1-5 at 8pm www.dansedanse.ca 514.842.2112 / 1.866.842.2112 Tickets: 41.50-70$ Peter Trosztmer is both dancer and conductor in AQUA KHORIA, his collaboration with musician-digital artist Zack Zettle. Set within the dome of the SAT, Trosztmer evolves against a 360-degree animated projection that reacts to light and movement. In the middle of the floor: a small circular pond.

As we enter the room, we are surrounded by buoys, gently rocking their bells in the middle of the night. After the doors close behind the last spectator, Trosztmer whips the waters into a storm with his rain dance, looking like Mickey Mouse moving brooms about with his magic. The tumultuous waters swallow us into the calmness of its depth, pushes us back out, and ultimately pulls us back in. Follows an exploration of this underwater world, like an animated documentary without voice-over narration where experience is privileged over knowledge. A drop of water falls into the pond. (How nice it would have been had it been mic’ed.) As the pond is lit, we perceive its reflection as light play on the dome, a sky made of water. Sometimes I find myself believing that through art we’re looking to capture something of nature that we’ve lost: the chaos and the beauty. It would explain why there’s so much art in the city and so little in the country. Trosztmer approaches the water on all fours. When he finally dips his paws in, he stands but remains hunched over. We are simultaneously witnessing evolution and regression as a human being goes back to the water that we came from. The drop of water falls on him before turning into a stream in a quasi-Flashdance moment, as Trosztmer is now down to his underwear. We reach a cave of moving shadows as Trosztmer walks around the space holding a candle, and travel through a tunnel without taking a single step. Trosztmer then goes back to playing conductor with his movement, which espouses the shape of the dome: height and circumference, what we are guessing are the two main ways of controlling the sound. The music is provided by harp-like-sounding notes from a synthesizer backed by a chill beat, which ends up sounding like Muzak for a spa. We then find ourselves in what looks like lava inside a whale (or at least its bones), like Jonah. Soon, the whale is caught in a whirlpool and we are spat back out to the surface of the water, now calm again, as seagulls fly overhead. There is something of IMAX in the simplistic narrative followed here: exposition (calm waters), conflict (storm), journey (cave), climax (whirlpool), resolution (calm waters). Of course, we’re more interested in the 360-degree projection than we are in the dance. Who could possibly compete with technology? There could be a ten-inch screen broadcasting hockey behind a dancer and we’d find ourselves watching the game. Some transitions could have been smoother as the music, projection and performance keep changing at the same time, but ultimately AQUA KHORIA does play like an IMAX movie: pleasant while it lasts but otherwise unmemorable. October 11-21 www.tangente.qc.ca / www.danse-cite.org 514.844.2033 Tickets: 25$ A month ago, I wrote that I go see dance because I love when people shut the fuck up. Yet last night I was ready to completely backtrack on this statement. It just goes to show that, with art, there is never any definite set of criteria that one can judge a work by, that art is chemistry that produces as many reactions as there are elements and audience members.

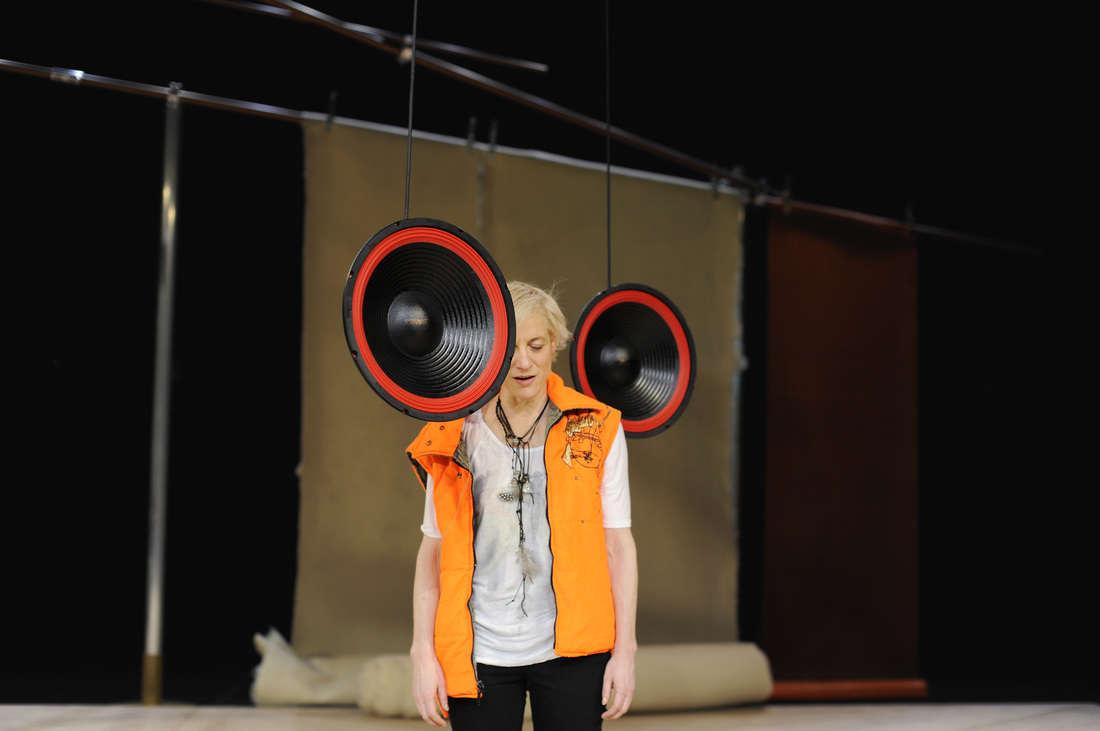

The occasion was Belgium-based American choreographer Meg Stuart’s unmissable return to Usine C with her solo Hunter. Her father was a community theatre director, she will tell us. As a result, she witnessed a lot of bad acting as a child, so she swore she’d never speak onstage. And for the first hour of this 90-minute show, she doesn’t. Treating her body as an archive of dance and memories, she moves in the style that has made her a contemporary dance icon. The collage aspect of the work is underlined incessantly, from the actual collage Stuart is making sitting at a table (and projected onto a screen at the back of the stage) at the beginning of the show to the sound collage by Vincent Malstaf and the video collage by Chris Kondek. I hear you loud and clear. It might be this aspect that most deters from the work. Like the soundtrack that moves through sound clips as though someone were switching through radio dials and never settling on any one channel, Stuart never sticks with anything for long, making us feel like we’re looking at a dancer improvising in the studio as she maintains a steady pace that comes across as manic. We want to tell her to calm down, to stand still for a moment. In her last show seen in Montreal, Built to Last, Stuart had touched on the ephemeral nature of dance by contextualizing it within a set that included a giant mobile of our solar system and mock-up of a T. rex skeleton. However, even though the set is also imposing in Hunter, it still replicates the blankness of the black box. In effect, it is like the table upon which Stuart does her collage: a rectangular blank surface on which beams are scattered around (like the pins used for her collage) from which rolls of fabric hang and are used as screens for the video projections. As a result, Stuart’s dance is decontextualized. What a welcomed change it is when she finally speaks. She maintains the stream of consciousness trope used throughout the show, but we do want to hear what she has to say about her life, about art, about anything. She’s Meg Stuart. She can speak onstage as much as she wants and we’ll listen. October 13-15 at 8pm www.agoradanse.com / www.usine-c.com 514.521.4493 Tickets: 38$ / Students or 30 years old and under: 30$ Going to Festival Quartiers Danses’s Programme triple at Cinquième Salle on Saturday night was like traveling to the past without experiencing nostalgia. The evening opened with Diane Carrière’s reconstruction of ABREACTION (1974), titled Et après… le silence for this version. What first strikes us is how far music for dance has come over the past forty years. Here it almost sounds parodic in its likeness to the cheaply dramatic scores for low-budget straight-to-video productions. It is even more dated than the affected modern movement. Dancer Sébastien Provencher, always reliable, uses all of his length as he extends his arms as far as they will go. Nothing to do about it though: isolated screams are always funny, no matter what they’re supposed to communicate. Carrière joins Provencher for the second half of the piece. How satisfying it is to watch older people dance. It is unfortunate that Carrière was otherwise so precious with her material, refusing to shake off the music or the video footage that anchored Et après as a dusty historical document instead of truly resurrecting it to make it relevant for a contemporary audience. Followed Victoria choreographer Jo Leslie with her duet Mutable Tongues. We’d already had the chance to see Leslie’s work at Tangente in 2011 with Affair of the Heart, an understated solo for Jacinte Giroux, a Montreal dancer whose speech and movement have been transformed by a stroke. Here again we found Giroux, this time accompanied by Louise Moyles, a dancer and storyteller from Newfoundland. Moyles walks into the room alternately speaking English and French. This self-translation makes everything she says sound phony. Giroux is lying face down on the stage, just outside the spotlight. She tells Moyles she’s had a stroke, but Moyles doesn’t listen, tells her to “get up” then to “lie down.” She is verbally abusive in a way that ableist culture is always abusive, even when it doesn’t use words, when instead of saying “get up” it just puts a staircase. We think of how choreographer Maïgwenn Desbois had subverted this idea by letting her neurodiverse dancers briefly choreograph her in Six pieds sur terre. With its burnt orange dresses, black tights, and heavy reliance on theatre, Mutable Tongues also feels a bit dated, not to mention that it is even more didactic than Carrière’s piece (which used voice-over to bring up such topics as hand-to-hand combat and PTSD). It reminded me of Chanti Wadge’s The Perfect Human (No. 2), which found its inspiration in dancers answering the question “Why do you move?” A young woman had walked to the front of the stage and screamed “I move because I hate talking!” I would turn it around and say that I go see dance because I love when people shut the fuck up. That’s certainly when Mutable Tongues is at its best. The evening concluded with Howard Richard’s Beaux moments, a piece for four women that was the most contemporary thing we got to see, though even then it was more akin to the beginnings of contemporary dance. There were moments that recalled Ginette Laurin’s work: the legs that were lifted while turning out at a 45-degree angle before the heels of the shoes thumped back down against the floor; the sideways lifts where a woman would throw herself under her partner’s arms so that she could lend on their thighs. However, Richard’s movement was less verbose and neurotic than Laurin’s. In the duets, the women also looked as if they were in each other’s way rather than working together. But even the electronic music and the costumes (black sleeveless dressed with red short-heeled shoes) had something of O Vertigo about them. There was also a solo set to Cat Power’s “The Greatest” that failed to fit with the rest of the piece as it flirted with the contemporary in a So You Think You Can Dance way.

The most positive aspect of the triple bill was the chance to see middle-aged women dance, including Estelle Clareton. But, if we were to base an opinion on this evening alone, we would be inclined to say that we’d rather watch older people dance rather than choreograph. Maybe La 2e Porte à Gauche had the right idea with Pluton. www.quartiersdanses.com September 6-17 514.842.2112 / 1.866.842.2112 Tickets: 25$ / Students or 30 years old and under: 20$ WARNING: spoilers.

La crème de la crème of Quebec celebrities (Sébastien Benoit) and their children (Sébastien Benoit’s child) were at the Bell Centre Wednesday for the first of a four-day run of Ice Age on Ice. The show begins with a squirrel finding an acorn. He buries it in… something and a rocket goes off. Follows a parade of the main characters of Ice Age on Ice: a sloth, a male and a female mammoth, two possums, a cougar, and their monkey friends. Though the dialogue is in French, all the songs are in English, so they sing “It’s your birthday / Happy birthday!” to mister mammoth in a surreal scene, like if one witnessed the 1990 live action Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles ice skating. (Did they do that yet?) The cougar’s back legs are paralyzed, but luckily they slide easily against the ice. The mammoths are also held up by wheelchairs, so it’s nice that there’s a positive message against ableism. Comes the triggering factor: the aforementioned acorn stuffing caused a volcano to wake up and it’s threatening to wipe out our heroes’ party with its lava. The sloth recalls a legend about an icy berry that freezes everything it touches, which seems like a rather simplistic solution to global warming. This gets exemplified by a dozen abstracted glittery snowflakes with Mohawks and a bird who spin to show they’re happy about the cold, which lets us know they’re not from Quebec. As the show is aimed at children, it’s not surprising to notice some slapstick, like when the sloth tries to catch a snowflake with its tongue and falls down. Children love to see people fall. Adults do too, but only when it’s not on purpose. So our heroes decide to go on a hunt for the icy berry in order to throw it in the volcano and freeze it over. The lady mammoth stays home though because that’s where women belong. There is also the inevitable complication in the shape of a female fox who wants the berry for herself because it would allow her to remain frozen in youth because women are vein and don’t care about being burned alive by lava just as long as they look good all the while. Enters a squirrel who is also female, which we know because she is limp-wristed, waves her arms around a lot and wears makeup, as lady squirrels do. She’s an acorn-digger who needs a male squirrel so he can give her his nuts because she can’t get them herself. Her boobs get in the way. Except that mister squirrel realizes he lost his nut and has a psychotic breakdown in what is by far the highlight of the show. He hallucinates sixteen acorns dancing around him in what can be best described as a psychedelic drug trip. Then there’s the Zamboni. No, wait… It’s just the mammoth’s big ass! I love fat jokes. Anyway, they get the frozen berry, the fox tries to steal it but fails by losing it in a hockey match and apologizes for her behaviour. She’s surprised that our heroes would still want to hang out with her, which is understandable because what a sausage party! But then it turns out that two possums ate the frozen berry. Why our heroes would leave the life-saving berry to animals who were clearly not aware of their plan is beyond me, but it doesn’t matter because it becomes obvious that the berry has no magical powers since the possums don’t turn to ice. Take that, magical-thinking solution to global warming! That’s when mister mammoth has an idea: what if they caused a snow avalanche that would put out the volcano by jumping up and down? (Does this even make sense scientifically?) He asks his lady what she thinks and she replies that she believes in him because she’s a supportive woman with no opinion of her own. I’ll let you guess how it ends. The show follows a simplistic structure: plot, figure skating, plot, figure skating, ad nauseam; like if Xavier Dolan was into the Ice Capades instead of slow motion. As with stories in contemporary dance, the two fail to connect in any meaningful way. All we perceive is the poverty of dance as a storytelling medium. Do we really need stories to make us swallow everything, including figure skating? There’s something almost patronizing about it, like Ice Age on Ice is just using characters kids already know and love to shove figure skating down their throat. As Spice World already pointed out back in 1997, it doesn’t matter what happens. Hell, nothing even needs to happen. All we need are those recognizable faces and we’ll eat it up. Ice Age on Ice did give me a few ideas as to how contemporary dancers could make more money though:

August 24-27 www.evenko.ca 1.855.310.2525 Tickets: 29.25-100.50$ As Festival TransAmériques draws to an end, spectators gather to watch nineteen individuals most of whom have no formal dance training take over the large stage of Monument-National and perform in French choreographer Jérôme Bel’s Gala. Cast in Montreal, they represent the diversity of the city: different ethnicities, different ages, different genders, different abilities, different body types.

The show opens with a long, shitty PowerPoint of different empty stages around the world, from the ancient to the technologically advanced, from the modest to the luxurious, from the small to the large. But their essence is the same: on one side, a group of people is meant to perform and, on the other, another group is meant to watch. In that space and in that relation, something could happen. We could be in any of these theatres, but we are in this one. In any case, what matters is the performance. The performance itself begins with a ballet section, a parade of the nineteen dancers performing a pirouette. First up is professional dancer Allison Burns so that the audience gets to see what the movement should actually look like as a reference point. The following non-dancers adapt the movement to their bodies, customize it for their skill level. While dancers can pick up a maximal set of cues because of their training, children and untrained adults only pick up the few that most characterize the movement for them. For example, a young boy simply lifts his arms over his head, actually holding hands, and spins. The exercise is then followed by a grande jeté. However, what comes across is that it’s not just a matter of skill, but also a matter of comfort with one’s body. Some performers come across as uncomfortable, which stiffens their movement. This is especially important because I feel it plays a large part in the discomfort that many experience with contemporary dance, even as spectators since the audience is always projecting itself onto the dancers. This explains the issues that some have with nudity onstage. Most people couldn’t allow themselves to do what dancers do alone in their own home, let alone on a stage in front of hundreds. This also partially explains why the children stand out in the improvised dance section. The cliché exists for a reason: they’re not as socially conditioned yet, they are less self-conscious, and they have fewer preconceived ideas about what dance is and what it’s supposed to look like, so their dance is freer. Édouard Lock said that the difference between dancers and non-dancers is in the legs. It’s visible here. Non-dancers make up for it by running around and moving their arms excessively. Unable to hide behind their skills, the non-professional dancers’ personality shines through: there’s the ham, the shy one, the funny one… The bows section, also using the parade structure, punctuated with applause for every single performer, makes one feel like Bill Murray’s character in Groundhog Day. Bel deals with the shortcomings that ableism imposes on all of us by having different performers choreograph for the entire group, the way Maïgwenn Desbois had in Six pieds sur terre. Seemingly no one expected a fat man to come out twirling the baton while the others keep dropping theirs. Everyone has something to offer. Despite its lazy structure, Gala is an undeniable crowd-pleaser. When the audience stood up for a warm standing ovation, it was the non-professional dancers they were applauding. It seems people like to see individuals who look like them onstage. Isn’t that surprising? June 7 & 8 at 8pm www.fta.ca 514.844.3822 Tickets: 34-50$ When the door opens, the action is already unfolding. On the other side of the door, the world is coated in a pinkish hue. A continuous loud high-pitched sound is oozing out. Through the spectators who have already found a seat, we see five dancers moving: Meryem Alaoui, Ellen Furey, Jolyane Langlois, Ann Trépanier, and Amanda Acorn, choreographer of multiform(s).

The audience is sitting on stands surrounding all four sides of the white stage, lending the performance the feel of a sporting event. Appropriately, the dancers are wearing sneakers. The rest of their outfits falls into a contemporary dance trend: nice bordering on fancy clothes that are joyfully mismatched. Whenever spectators are allowed to sit on multiple sides of the stage, I am always surprised to notice that the feeling of the proscenium stage remains. It reminds me that, despite the conventions of theatre, dance is truly three-dimensional and that it is only ever possible to see from one’s own perspective. Though the movement differs from one performer to another, it answers to the same constraints: their bodies are forever in motion and involved in repetitions. Back and forth, from one side to the other, like a pendulum. This swinging often leads the cylindrical body into rotations. They reminds us of mechanical toys that inevitably have a limited movement range, except that the dancers’ movement changes over time, ever so slightly, but undeniably. This rocking motion can at times induce motion sickness, an experience the spectators apparently share with the performers. It is an exercise of endurance for the dancers that is hypnotic for the audience. The performers converge to the middle of the stage, their movement becoming synchronous and picking up speed. Synchronicity focuses the gaze; dissimilarity diffuses it. Synchronicity feels light. It’s like forgetting yourself. Yet when one of the dancers falls out of it, it’s her we’d rather be. She’s the one who looks free. With its clear concept and perpetual motion, multiform(s) shares many similarities with Henderson/Castle: voyager by Ame Henderson. However, in voyager, dancers can’t repeat any movement so that the end result is less defined, more eclectic. In multiform(s), the repetitions appear to be an outlet, like in Julia Male’s solos. As in Guilherme Botelho’s Sideways Rain and the walking that takes up most of Olivier Dubois’s Tragédie, we also feel that this could go on forever, that in fact it has been. Different images emerge depending on the body parts that the movement brings into action. Front to back movement looks like prayer; sometimes one might even say like divine possession. Lunges inevitably remind one of the repetitions involved in exercise. And, though the arms never carve the infinity sign in the air, it is seen everywhere. One is even inclined to believe that the dancers might be immortal. June 5-7 at 9pm www.fta.ca 514.844.3822 Tickets: 30$ / 30 ans et moins: 25$ Lara Kramer is an Oji-Cree (Ojibwe and Cree) choreographer and performer whose work is intimately linked to her memory and Aboriginal roots. She received her BFA in Contemporary Dance at Concordia University. Working with strong visuals and narrative, Kramer’s work pushes the strength and fragility of the human spirit. Her work is political and potent, often examining issues surrounding Canada and First Nations Peoples. Kramer has been recognized as a Human Rights Advocate through the Montreal Holocaust Memorial Centre. Her work has been presented at the OFFTA, The First Peoples Festival, Festival Vue Sur la Relève, The Talking Sticks Festival, Canada Dance Festival, The Banff Centre, MAI (Montréal, arts interculturels), Public Energy, Planet IndigenUS, Dancing on the Edge, Tangente, New Dance Horizons, Alberta Aboriginal Arts, The Expanse Movement Arts Festival and Native Earth Performing Arts. Her acclaimed work Fragments, inspired by her mother’s stories of the Indian Residential Schools of Canada, has brought her recognition as one of Canada’s bright new talents. She has been on the faculty of the Indigenous Dance Residency at The Banff Centre.

Why do you move? It’s an expression of my history, my storyline, my connection to and understanding of this current place and time. Of what people have said about your work (good or bad), what has most stuck with you? The need of these stories having a place, of carving a space for the stories I tell; especially specific to Native Girl Syndrome, just the importance it has in our present time. What are you most proud of? Being a mother. Speaking of my work, it’s an interesting process; I always feel like I’m navigating this place of decolonization. I feel proud in that my process allows me to further understand what the impact of the residential schools – but it goes beyond that – the impact cultural genocide has had on my lineage. That also goes back to the proudness I feel being a mother. My work allows me to deconstruct all that and understand it and process it. How do you feel about dance criticism? I think it’s good. When we shy away from that process of having dance criticism, there’s something… The politeness, you can feel it sometimes. That’s the good part of art, when you can dig deep and critique it on many levels. What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever been given? I think just being told that dance is a lot of hard work. I don’t know if that’s advice or more “That’s the reality.” Maybe the advice that was given and that I feel has resonated to be true is that what I source as a choreographer isn’t found in the studio at all. The advice early on was that my life experience, my experience out in the world, outside of the studio, is what is gonna be my food. Maybe that sounds basic or “no kidding”, but when you’re brought up in that classical ballet world, that sort of “you gotta be in the studio to be creating”, maybe that idea comes off as foreign. It sounds weird, but the more time I take away from the form and actually just being in situations connects me to something more interesting in my work. What does dance most need today? Tolerance. It’s tricky because I think it’s important that art speaks for itself, but being a First Nations artist is always something that becomes the focus or a thing that has to be explained or justified or contextualised, and there’s not always a place for it in mainstream dance. Like anything and any art form, there’s still a hierarchy that takes place and I think that’s unfortunate when we’re talking about art. It’s limiting. Also – this is a personal preference and not a comment on a specific community – it’s this feeling that even the idea of dance… What I’m also interested in and where my work has shifted is that, dissecting it and breaking it down – again it’s going back to tolerance – I’ve had people say my work is not dance enough, whatever that means. I’m working with many elements and for me the expression is “that of the body.” To sum that up, it’s just that idea of breaking down those hierarchical systems and looking at art as something broader and limitless. Given the means, which dance fantasy would you fulfill? If I had all the means, it would probably be an odd place to exist as an artist. I have a fantasy – and it doesn’t seem intangible – but it’s more connecting to the wisdom and knowledge of traditional dance and that deeper link to the land and ancestors. What motivates you to keep making art? I’m always investigating this undercurrent of violence and trauma that exists in Canada that is the result of what has happened and continues to happen to First Nations people. My motivation and desire is to try to embed myself into a more indigenous perspective so that that becomes more of what’s expressed. The trauma is so deep and there are so many layers, generation after generation, that it feels like an endless journey. Native Girl Syndrome March 10-19 at 7:30pm www.espacelibre.qc.ca 514.521.4191 Tickets: 25$ / 30 years old and under: 22$ A minimalist at heart, Dorian Nuskind-Oder’s compositions emerge from a process that emphasizes economy of means and physical precision. Conceptual, but not cold, her work searches for poetic complexity through the cultivation of simple but ambiguous images. After completing her training at New York University and the Merce Cunningham Studio, Dorian worked as a freelance dancer and video editor in New York from 2004 until 2009, when she relocated to Montreal. Upon her arrival in Quebec, Dorian began collaborating with visual artist Simon Grenier-Poirier under the company name Delicate Beast. Supported by organizations like the Conseil des Arts de Montréal, Circuit-Est Centre Chorégraphique, Studio 303, and Tangente, the company has created four works, which have been presented in Montreal, Quebec City, Halifax, Boston, and Nottingham (UK).

Why do you move? It's pretty simple, actually: I move because it feels good and connects me to my body and the bodies of those around me. Also, it's virtually impossible for me to be dancing and thinking about my e-mail at the same time. What are you most proud of? In general, I have a lot of admiration for my own and other artists’ capacity to continue to create in the face of frequent rejection. I recently told someone that this sense of resilience is our superpower, and I totally believe that. What or who was your first dance love? I remember seeing John Jasperse's work for the first time at the American Dance Festival in 1999. I was sixteen. Up to that point, my training had been in classical ballet, and I had always felt like a bit of an outsider. Seeing John's work – which is really meticulous and prickly and sensual and cerebral – that was the first time I looked at a choreography and felt genuinely engaged. What does dance most need today? More time, less product. How do you feel about dance criticism? It is a process I am a part of, not something that is being done to me. Given the means, which dance fantasy would you fulfill? I'd build an Art Farm, a retreat in the woods where artists can come and work for intensive periods of time, while also hanging out with horses and dogs, and taking walks through wide open fields. I like living in the city, but I create more productively in places where I can see the horizon. I also like the idea of having a space that I could share with many other people. What motivates you to keep making art? The social nature of performance-making and performance-watching are super important to me. Both require a level of vulnerability and risk-taking that I otherwise would not experience in my day-to-day life. Looking at and making art requires a practice of remaining open and curious in the face of strangeness or not understanding. This practice feels important both to my own life and to society as a whole. Memory Palace February 25-28 www.tangente.qc.ca 514.871.2224 Tickets: 23$ / Students: 19$ |

Sylvain Verstricht

has an MA in Film Studies and works in contemporary dance. His fiction has appeared in Headlight Anthology, Cactus Heart, and Birkensnake. s.verstricht [at] gmail [dot] com Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed