|

1. Judson Church is Ringing in Harlem (Made-to-Measure) / Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at the Judson Church (M2M), Trajal Harrell + Thibault Lac + Ondrej Vidlar (Festival TransAmériques) American choreographer Trajal Harrell’s work has always been impressive if only for its sheer ambition (his Twenty Looks series currently comprises half a dozen shows), but Judson Church is Ringing in Harlem (Made-to-Measure) is his masterpiece. In the most primal way, he proves that art isn’t a caprice but that it is a matter of survival. Harrell and dancers Thibault Lac and Ondrej Vidlar manifest this need by embodying it to the fullest. The most essential show of this or any other year. 2. ENTRE & La Loba (Danse-Cité) & INDEEP, Aurélie Pedron Locally, it was the year of Aurélie Pedron. She kept presenting her resolutely intimate solo ENTRE, a piece for one spectator at a time who – eyes covered – experiences the dance by touching the performer’s body. In the spring, she offered a quiet yet surprisingly moving 10-hour performance in which ten blindfolded youths who struggled with addiction evolved in a closed room. In the fall, she made us discover new spaces by taking over Montreal’s old institute for the deaf and mute, filling its now vacant rooms with a dozen installations that ingeniously blurred the line between performance and the visual arts. Pedron has undeniably found her voice and is on a hot streak. 3. Co.Venture, Brooklyn Touring Outfit (Wildside Festival) The most touching show I saw this year, a beautiful portrait of an intergenerational friendship and of the ways age restricts our movement and dance expands it. 4. Avant les gens mouraient (excerpt), Arthur Harel & (LA)HORDE (Marine Brutti, Jonathan Debrouwer, Céline Signoret) (Festival TransAmériques) wants&needs danse’s The Total Space Party allowed the students of L’École de danse contemporaine to revisit Avant les gens mouraient. It made me regret I hadn’t included it in my best of 2014 list, so I’m making up for it here. Maybe it gained in power by being performed in the middle of a crowd instead of on a stage. Either way, this exploration of Mainstream Hardcore remains the best theatrical transposition of a communal dance I’ve had the chance to see. 5. A Tribe Called Red @ Théâtre Corona (I Love Neon, evenko & Greenland Productions) I’ve been conscious of the genocide inflicted upon the First Nations for some time, but it hit me like never before at A Tribe Called Red’s show. I realized that, as a 35 year-old Canadian, it was the first time I witnessed First Nations’ (not so) traditional dances live. This makes A Tribe Called Red’s shows all the more important. 6. Naked Ladies, Thea Fitz-James (Festival St-Ambroise Fringe) Fitz-James gave an introductory lecture on naked ladies in art history while in the nude herself. Before doing so, she took the time to look each audience member in the eye. What followed was a clever, humorous, and touching interweaving of personal and art histories that exposed how nudity is used to conceal just as much as to reveal. 7. Max-Otto Fauteux’s scenography for La très excellente et lamentable tragédie de Roméo et Juliette (Usine C)

Choreographer Catherine Gaudet and director Jérémie Niel stretched the short duo they had created for a hotel room in La 2e Porte à Gauche’s 2050 Mansfield – Rendez-vous à l’hôtel into a full-length show. What was most impressive was scenographer Max-Otto Fauteux going above and beyond by recreating the hotel room in which the piece originally took place, right down to the functioning shower. The surreal experience of sitting within these four hyper-realistic walls made the performance itself barely matter.

1 Comment

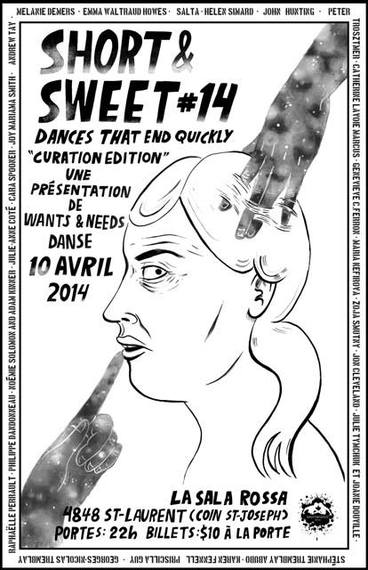

On April 10, Wants&Needs Danse will be presenting the 14th edition of their popular Short&Sweet series in conjunction with the Art Curator's Association of Quebec's "Envisioning the Practice" conference, which looks at Performing Arts Curation. For the occasion, here is an interview that had been conducted with organizers Sasha Kleinplatz and Andrew Tay for the 7th edition of Short&Sweet. SYLVAIN VERSTRICHT: I've been thinking about [Short&Sweet] in terms of artistic direction and, given the high number of choreographers that get to show work, that maybe the best artistic direction is to have none at all. How do you choose who is going to present work? SASHA KLEINPLATZ: I think what we do is try to get people who represent different parts of the contemporary dance community in Montreal. Basically, we will try to make sure we have artists who are young, mid-career, and established. We also try to have a balance between different types of work, i.e. artists who create more cerebral or conceptual work versus artists who create work that is very movement based. We also try to include some artists who aren't necessarily working in the contemporary dance milieu; for example, we have asked clowns, performance artists, hip hop choreographers and puppeteers in the past. I think as curators we believe our challenge with Short&Sweet is community building and creating dialogue. At the same time we try to ask people who we think would make good use of this particular kind of performance situation. SYLVAIN: It also seems that, even though the Montreal dance community is rather small and everyone knows each other, there is still a bit of a divide between francophone and anglophone artists. Short&Sweet is one of the few times when I feel like that line gets somewhat erased. Am I wrong in assuming this and is this something that's important to you? ANDREW TAY: It is definitely something that we think about, and we feel like this is part of what makes Short&Sweet fun and interesting. Homogeny can definitely be boring and every good party needs a good mix of people. I think that we are trying to breed a curiosity among artists to see all the different types of dance ideas that are out there no matter where they are coming from. This curiosity creates an atmosphere that transcends boundaries such as language... We also think this situation is really unique to Montreal and important! I was at a symposium recently that was talking about the so-called anglo - franco culture divide and some people were arguing that a bilingual audience doesn't exist. I totally disagree with this and I think events like Short&Sweet prove it is an exciting possibility. I think we are lucky since dance is not necessarily a language-based art form and because of this we have more opportunity to cultivate this kind of audience. SYLVAIN: For this edition of Short&Sweet, you asked choreographers to collaborate with artists from other disciplines. Dance always strikes me as being particularly collaborative, so I was wondering how this constraint concretely affected your piece this time around… SASHA: I know for me it felt like an opportunity to take a chance with collaborators I have never worked with before. Because the piece is short I felt comfortable treating the collaboration as a blind date between myself and the two collaborators and interpreters (musician John Milchem, performance artist Adriana Disman, and interpreters Nathan Yaffe and Susan Paulson). We have all agreed that the process of the collaboration is as interesting as the outcome/performance. We were all just excited to see what working together yields. For me this goes back to the original spirit of experimentation and risk-taking that I was looking for when Andrew and I conceived of Short&Sweet. Short & Sweet #14 April 10 at 10pm La Sala Rossa https://www.facebook.com/events/371765872964691/?fref=ts Tickets: 10$  Levée des conflits, photo by Caroline Ablain Levée des conflits, photo by Caroline Ablain As my years as a dance critic pile on, it’s probably to be expected that I see more and more works I’ve already seen. This year, I can think of at least five off the top of my head. The one that most stood up to a repeat viewing was Matija Ferlin and Ame Henderson’s The Most Together We’ve Ever Been. I took the bus to Ottawa to see it just as a snowstorm was hitting the city. The ride ended up taking four hours. I barely had enough time to shove some of the worst food I’ve ever had in my mouth before running over to Arts Court, an old courthouse that has been turned into a beautiful art space. And, as soon as the show started, I knew it was all worth it. Back in Montreal, Israeli choreographer Sharon Eyal made a much-anticipated return after six years with Corps de Walk, a show she created with her partner Gai Behar. The uniformity she imposed on the twelve dancers of Norway’s Carte Blanche was oppressive and disturbing. It was its own indictment of homogeneity. At the Biennale de gigue contemporaine, the always reliable Nancy Gloutnez stood out yet again. With Les Mioles, she borrowed from classical music and became a conductor, turned her dancers’ feet into instruments, and composed a score reminiscent of Steve Reich in its obsessive build-up. After years of being one of the most rigorous emerging choreographers in Montreal, Sasha Kleinplatz has now fully emerged with Chorus II. The audience stood above six male dancers who swayed between demonstrations of physical strength and chill-inducing vulnerability. It is now up to venue artistic directors everywhere to shine on Kleinplatz the spotlight she so clearly deserves. Speaking of which, 2013 was the year of Agora de la danse. They probably had their best programming since I started following dance. It all began with Karine Denault’s Pleasure Dome, in which musicians and dancers explored pleasure without ever lazily resorting to shortcuts. Rather, she allowed the meaning of the work to emerge on its own and for Pleasure Dome to impose itself by the same token. It was followed by When We Were Old, a duo by Québec’s Emmanuel Jouthe and Italy’s Chiara Frigo (presented in collaboration with Tangente). The choreographer-dancers managed to bypass every single contemporary dance cliché that usually occurs as soon as a man and woman are onstage. In each and every moment, their encounter felt fresh and sincere. Agora ended the year with Prismes by Benoît Lachambre, who a month later would win the Montreal Dance Prize. Created for Montréal Danse, Prismes explored the effect of light on perception in a chromatic environment, as well as the fluidity of gender. Lighting designer Lucie Bazzo outdid herself for this highly experiential work. At the Festival TransAmériques, it was French choreographer Boris Charmatz who stood out with Levée des conflits, an opus of twenty-five movements repeated as a canon by twenty-four dancers. From the simplicity of the choreography to the high number of performers, Levée des conflits impressively hovered between minimalism and excess. I spent the summer in Iceland, where my trip ended with the Reykjavík Dance Festival. There, Norway’s Sissel M Bjørkli presented one of the most singular shows I’ve ever seen with Codename: Sailor V. It took place in a tiny space, barely big enough to seat fifteen. The smoke that filled the room along with Elisabeth Kjeldahl Nilsson and Evelina Dembacke’s intensely saturated coloured lighting blurred the edges of everything. Inspired by anime, Bjørkli created an alter ego for herself and through imaginative play managed to turn an office chair into a spaceship. That shit was magical. So was Nothing’s for Something by Belgium’s Heine Avdal and Yukiko Shinozaki, which opened with a ballet for six curtains, each suspended by six huge helium-filled balloons. Set to classical music, it was reminiscent of Disney’s Fantasia. For its finale, eight such balloons were left to float around the room while emitting breathing sounds, appearing like disembodied alien visitors. Soon after my return to Montreal, Marie Chouinard presented Henri Michaux : Mouvements. The genesis of this work, when Carol Prieur first incarnated the drawings of Henri Michaux back in 2005, is the reason why I’m a dance critic today. Seeing the twelve dancers of Chouinard’s company lend themselves to the exercise was just as riveting eight years later. By translating drawings into movement, Chouinard demonstrated the power of dance to think the body creatively. Usine C ended the year on a high note with their program from the Netherlands, most especially Ann Van den Broek’s feminist work for three female dancers, Co(te)lette. The show was powerful in its exposition of women’s bodies as a site of tension, torn between being objects of desire and embodied subjects. We can only hope that there will be more works like it in 2014.  Chorus II, photo by Jasmine Allan-Côté Chorus II, photo by Jasmine Allan-Côté Sylvain Verstricht 12 Apr (4 days ago) to sasha Hi Sasha, Would you want to talk to me about your new show? Do you have time? (Preferably by email, but we could do it in person if need be. Or maybe even chatting?) I hope all is well. xo Sash 12 Apr (4 days ago) to me Hey, Email is great:) Cheers Sylvain Verstricht 12 Apr (4 days ago) to Sash You went from a "man free zone" in your last work [All the Ladies] to an all-male cast for your new show, Chorus II. Why the switch? sasha kleinplatz 13 Apr (3 days ago) to me I think it had to do with the subject matter (davening), which I remember my grandfather performing. He was a really tough guy, but when he prayed he could be so tender and meditative. I was interested in exploring that "energy" with a group of male dancers, as a way of remembering and re-writing my experiences of him. Sylvain Verstricht 13 Apr (3 days ago) to sasha Your performers come from a variety of backgrounds: different schools; some are barely out of them, others have been dancing professionally for a while... It almost seems as though you handpicked them. Why these particular men? sasha kleinplatz 13 Apr (3 days ago) to me When I first started working on this piece it was for Piss in the Pool, and I knew I wanted as many men as possible. I wanted it to be a counter-point to the twelve-women choreography I made for the pool two years earlier. I basically wrote every male dancer I knew, as well as a bunch I barely knew who were recommended to me by friends. Anybody who said "yes" was in the choreography (not the most professional method but it worked amazingly). Most of those original dancers are still in the work. Sylvain Verstricht 14 Apr (2 days ago) to sasha Since you bring it up, you have been working on it for a while... I always admired you for your rigor, so I have to ask: how do you manage to maintain interest in one piece for such a long period of time? How has it changed over time? sasha kleinplatz 14 Apr (2 days ago) to me Oh man, it is hard to stay rigorous! It isn't hard to stay interested, but it's hard to stay committed to the thread of the work and not diverge into ideas that are outside the particular choreography I am making. It helps to have collaborators who can also see the themes of the work pretty clearly; they keep you on track. The interpreters (Benjamin Kamino, Milan Panet-Gigon, Nate Yaffe, Lael Stellick, Simon Portigal, and Frédéric Wiper) are amazing for this, they all have their own experience and perceptions of the work, and if they feel like we have strayed too far from the universe we have created they will tell me. Working with a perceptive outside eye is also really integral. For this piece I have worked with three (Thea Patterson, Andrew Tay, Ginelle Chagnon), all of whom have pushed me to retain and clarify the voice of the work. It also helps to be feel a bit possessed by the work:) Sylvain Verstricht 14 Apr (2 days ago) to sasha During the public performance following your residence at Usine C, one of the dancers let his partner fall a bunch of times. Based on their interaction after the show, I assume that wasn't supposed to happen. Question: have you been experiencing massive amounts of guilt or was it their own fault? sasha kleinplatz 14 Apr (2 days ago) to me That's a hilarious question. Um, no I don't feel guilty. I am a pretty paranoid choreographer, I am constantly asking the dancers if a movement feels safe to them to execute, to a degree that the dancers have point-blank told me is very annoying. So, I had asked them about that part repeatedly before the showing, and afterwards when I asked the dancer if he was okay he basically laughed at me. Sylvain Verstricht 15 Apr (1 day ago) to sasha One last question... After you presented Chorus II at Piss in the Pool, I compared it to Édouard Lock's work (mostly just because of the black suits the men wore). I used the word "emptied" ("un Édouard Lock vidé de ses muses féminines"), which I now realize sounds pejorative, but I really meant it as a compliment. Do you hate me? sasha kleinplatz 23:44 (15 hours ago) to me No, I love you, you know that. I was kind of like "fuck, my work looks derivative!" but that's okay. Can't let Locke corner the market on men in suits. Anyways, it's all good, we are good:) April 18-20 at 8pm & April 21 at 3pm MAI www.m-a-i.qc.ca 514.982.3386 Tickets: 22$ / Students: 15$ My wish for the Montreal dance scene in 2013 is for Marie-Hélène Falcon to quit her job as artistic director of the Festival TransAmériques. I’m hoping she’ll become the director of a theatre so that the most memorable shows will be spread more evenly throughout the year instead of being all bunched up together in a few weeks at the end of spring. With that being said, here are the ten works that still resonated with me as 2012 came to an end. 1. Cesena, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker + Björn Schmelzer (Festival TransAmériques)

I’ve been thinking about utopias a lot this year. I’ve come to the conclusion that – since one man’s utopia is another’s dystopia – they can only be small in nature: one person or, if one is lucky, maybe two. With Cesena, Belgian choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker showed me that it could be done with as many as nineteen people, if only for two hours, if only in a space as big as a stage. Dancers and singers all danced and sang, independently of their presupposed roles, and sacrificed the ego’s strive for perfection for something better: the beauty of being in all its humanly imperfect manifestations. They supported each other (even more spiritually than physically) when they needed to and allowed each other the space to be individuals when a soul needed to speak itself. 2. Sideways Rain, Guilherme Botelho (Festival TransAmériques) I often speak of full commitment to one’s artistic ambitions as extrapolated from a clear and precise concept carried out to its own end. Nowhere was this more visible this year than in Botelho’s Sideways Rain, a show for which fourteen dancers (most) always moved from stage left to stage right in a never-ending loop of forward motion. More than a mere exercise, the choreography veered into the metaphorical, highlighting both the perpetual motion and ephemeral nature of human life, without forgetting the trace it inevitably leaves behind, even in that which is most inanimate. More importantly, it left an unusual trace in the body of the audience too, making it hard to even walk after the show. 3. (M)IMOSA: Twenty Looks or Paris Is Burning at the Judson Church (M), Cecilia Bengolea + François Chaignaud + Trajal Harrell + Marlene Monteiro Freitas (Festival TransAmériques) By mixing post-modern dance with queer performance, the four choreographer-dancers of (M)IMOSA offered a show that refreshingly flipped the bird to the usual conventions of the theatre. Instead of demanding silence and attention, they left all the house lights on and would even walk in the aisles during the show, looking for their accessories between or underneath audience members. Swaying between all-eyes-on-me performance and dancing without even really trying, as if they were alone in their bedroom, they showed that sometimes the best way to dramatize the space is by rejecting the sanctity of theatre altogether. 4. Goodbye, Mélanie Demers (Festival TransAmériques) Every time I think about Demers’s Goodbye (and it’s quite often), it’s always in conjunction with David Lynch’s Inland Empire. The two have a different feel, for sure, but they also do something quite similar. In Inland Empire, at times, an actor will perform an emotional scene, and Lynch will then reveal a camera filming them, as if to say, “It’s just a movie.” Similarly, in Goodbye, dancer Jacques Poulin-Denis can very well say, “This is not the show,” it still doesn’t prevent the audience from experiencing affect. Both works show the triviality of the concept of suspension of disbelief, that art does not affect us in spite of its artificiality, but because of it. 5. The Parcel Project, Jody Hegel + Jana Jevtovic (Usine C) One of the most satisfying days of dance I’ve had all year came as a bit of a surprise. Five young choreographers presented the result of their work after but a few weeks of residencies at Usine C. I caught three of the four works, all more invigorating than some of the excessively polished shows that some choreographers spend years on. It showed how much Montreal needs a venue for choreographers to experiment rather than just offer them a window once their work has been anesthetically packaged. The most memorable for me remains Hegel & Jevtovic’s The Parcel Project, which began with a surprisingly dynamic and humorous 20-minute lecture. The second half was an improvised dance performance, set to an arbitrarily selected pop record, which ended when the album was over, 34 minutes later. It was as if John Cage had decided to do dance instead of music. Despite its explanatory opening lecture, The Parcel Project was as hermetic as it was fascinating. 6. Spin, Rebecca Halls (Tangente) Halls took her hoop dancing to such a degree that she exceeded the obsession of the whirling dervish that was included in the same program as her, and carried it out to its inevitable end: exhaustion. 7. Untitled Conscious Project, Andrew Tay (Usine C) Also part of the residencies at Usine C, Tay produced some of his most mature work to date, without ever sacrificing his playfulness. 8. 1001/train/flower/night, Sarah Chase (Agora de la danse) Always, forever, Sarah Chase, the most charming choreographer in Canada, finding the most unlikely links between performers. She manages to make her “I have to take three boats to get to the island where I live in BC” and her “my dance studio is the beach in front of my house” spirit emerge even in the middle of the city. 9. Dark Sea, Dorian Nuskind-Oder + Simon Grenier-Poirier (Wants & Needs Danse/Studio 303) Choreographer Nuskind-Oder and her partner-in-crime Grenier-Poirier always manage to create everyday magic with simple means, orchestrating works that are as lovely as they are visually arresting. 10. Hora, Ohad Naharin (Danse Danse) A modern décor. The legs of classical ballet and the upper body of post-modern dance, synthesized by the athletic bodies of the performers of Batsheva. These clear constraints were able to give a coherent shape to Hora, one of Naharin’s most abstract works to date. Scrooge Moment of the Year Kiss & Cry, Michèle Anne De Mey + Jaco Van Dormael (Usine C) Speaking of excessively polished shows… La Presse, CIBL, Nightlife, Le Devoir, and everyone else seemingly loved Kiss & Cry. Everyone except me. To me, it felt like a block of butter dipped in sugar, deep fried, and served with an excessive dose of table syrup; not so much sweet as nauseating. It proved that there’s no point in having great means if you have nothing great to say. Cinema quickly ruined itself as an art form; now it apparently set out to ruin dance too. And I’m telling you this so that, if Kiss & Cry left you feeling dead on the inside, you’ll know you’re not alone.  Sasha Kleinplatz's Chorus Two..., photo by Celia Spenard-Ko Sasha Kleinplatz's Chorus Two..., photo by Celia Spenard-Ko À la sortie de Piss in the Pool, que retient-on cette année? Surtout Flotsam, la pièce de Leanne Dyer pour laquelle les cinq interprètes sont cachés sous d’imposants costumes composés de centaines de sacs de plastique. Trois grosses boules couleur vert menthe – les sacs du Supermarché PA – mais dont la couche s’avère être gracieuseté du Jean-Coutu, et deux chenilles de plastique, une blanche et l’autre noir (on se tient ici dans la palette limitée de Glad). C’est un défilé de mode, c’est un rituel consommateur, mais c’est surtout un petit monde étrange et aux images marquantes. On remarque aussi la rigueur que la chorégraphe Sasha Kleinplatz amène à tous ses projets avec Chorus Two… Après s’être entouré de femmes pour All the Ladies, c’est maintenant sur cinq hommes qu’elle projette son travail toujours très physique. Avec leurs complets noirs, les danseurs font penser à un Édouard Lock vidé de ses muses féminines. La New Yorkaise Shannon Gillen offre une introduction à la soirée qui nous plonge immédiatement dans un univers inquiétant avec WOLFMAN Redux. Le visage de la seule danseuse au fond de la piscine est recouvert de papier métallique. Son mouvement reflète le désarroi et l’anxiété que pourrait causer un manque d’oxygène. Ces trois pièces se retrouvent toutes en première partie, alors on peut deviner que la deuxième n’est pas tout à fait du même calibre. Toutefois, il y a Manuel Roque qui se démarque avec trou (pour deux) (à capella), un duo aux airs de compétition sadique qu’il danse avec Lucie Vigneault. Piss in the Pool 2011 18 juin à 20h30 Bain Saint-Michel, 5300 Saint-Dominique www.montrealfringe.ca 514.849.FEST (3378) Billets : 12$ |

Sylvain Verstricht

has an MA in Film Studies and works in contemporary dance. His fiction has appeared in Headlight Anthology, Cactus Heart, and Birkensnake. s.verstricht [at] gmail [dot] com Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed