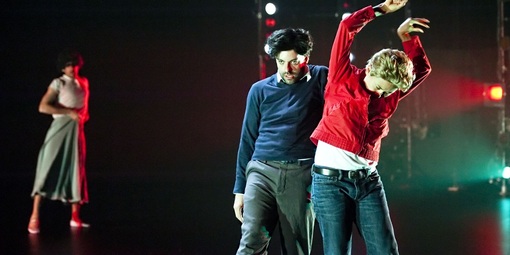

(M)IMOSA, photo de Paula Court (M)IMOSA, photo de Paula Court C’est bien d’avoir un groupe d’adolescentes dans un spectacle de danse. On peut souvent se fier à leurs réactions pour savoir si quelque chose d’intéressant se passe. Si elles se regardent constamment pour savoir comment elles devraient réagir (car on sait que, lorsqu’on est adolescent, les réactions individuelles sont interdites), c’est bon signe. C’est bien l’art qui laisse perplexe, face auquel même notre réaction ne peut être simpliste. C’est ce qui s’est passé lors de la représentation de (M)IMOSA: Twenty Looks or Paris Is Burning at the Judson Church (M) en cette deuxième journée du Festival TransAmériques. Ce n’est peut-être pas surprenant étant donné que, comme le sous-titre l’indique, le chorégraphe new-yorkais Trajal Harrell croise la culture queer avec la vision démocratique du mouvement des chorégraphes postmodernes. Et il n’est pas le seul chorégraphe-interprète. Il y en a trois de plus, rassemblant aussi Paris et Lisbonne : Cecilia Bengolea, François Chaignaud et Marlene Monteiro Freitas. On pourrait avoir peur que ce soit chaotique, et ce l’est, mais non pas à cause du nombre de chorégraphes, mais bien dû à l’esthétique postmoderne. Ironiquement, c’est aussi celle-ci qui permet au spectacle de faire preuve de cohésion. Le courant postmoderne a donné de la fraicheur à la danse. (« Ça respire, » j’ai écrit dans mes notes.) Il y a quelque chose de libérateur lorsque les gens cessent de se soucier du beau, du sexy. Ça fait du bien être laid ou ridicule de temps en temps. On retrouve dans (M)IMOSA le mouvement au quotidien, comme si les interprètes ne faisaient que danser dans leur chambre à coucher en chantant leur chanson du moment, sans trop se forcer, et que nous avions la chance de les espionner. D’un autre côté, il y a la performance « all eyes on me » des voguers et drag queens et kings. On peut d’abord se rappeler Spoken Word/Body de Martin Bélanger, et ensuite Pow Wow de Dany Desjardins, mais (M)IMOSA réussit mieux la transition au théâtre. Peut-être que la relation avec le public en est la raison. Les lumières continuent d’éclairer les spectateurs durant la pièce, comme pour nous faire sentir qu’on fait partie intégrale du spectacle. On fait fi de la religiosité conventionnelle de la performance théâtrale, et c’est ce qui finit par théâtraliser le tout. Les interprètes se promènent parmi le public et cherchent leurs accessoires dans les rangées sans se soucier du bruit qu’ils font. Il y a aussi quelque chose de rafraichissant à voir des interprètes de talent refuser la virtuosité, en faire moins qu’ils en sont clairement capables. Le talent se laisse alors deviner ici et là, et il n’en ait que plus réjouissant. En tout cas, leur confusion initiale passée, les adolescentes ont eu l’air de vraiment tripper. (M)IMOSA 25-26 mai à 21h Cinquième Salle www.fta.qc.ca 514.844.3822 / 1.866.984.3822 Billets à partir de 35$

0 Comments

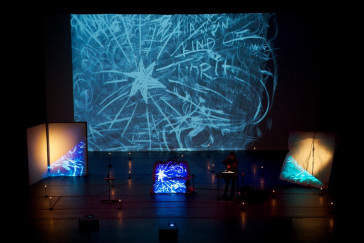

Laurie Anderson's Delusion, photo by Leland Brewster If the world is going to end, Laurie Anderson might as well be your travelling companion. That’s at least how she made me feel last night at the Montreal premiere of her show Delusion. Though the many stories she tells over the 90 minutes the show lasts might at first appear eclectic, a sense of the end of the world pervades all of them, or at the very least the end of life. Ends even, for as she points out, from the moment we come into this world, we are destined for multiple deaths. The scenography is simple, even basic, but effective. A rock-like structure in the middle of the stage acts as a screen for smaller grey rocks that constantly mutate in watery ripples. On the screen at the back, the largest of four, a small wooden frame appears within which, appropriately, leaves fall. This is not only coincidental; as we will find out, Delusion takes place within a perpetual, rainy autumn. The Great Flood. On either side, two smaller screens. The one on the left, like the blank pages of an open book; on the right, rippled like the bed sheet of an unmade bed. The latter is also the first image to appear on them, sheets of a peachy skin colour. Unlike Anderson’s recorded material, highly cerebral, the music she creates for the show is surprisingly cinematic, sometimes even downright emotional. As she takes on a deep electronically modified male voice, her mysterious synth composition is reminiscent of Angelo Badalamenti’s score for Twin Peaks. It is just as probable that things might turn out to be gloomy or funny. The darkness of the candle-lit room, the smoke that fills the screens as well as the stage itself, visible in the narrow strips of light, and the red curtains on video all facilitate the comparisons to David Lynch, as cliché as those might be. The incessant music cradles the audience from left to right, allowing them to comfortably settle into the slow and hypnotic show. From early on, Anderson commands a certain reverence. There is indeed something mythic about her. She is as comfortable on stage as any performer I have ever seen. She playfully interacts with the projection, swaying her foot in front of the projector beam so that its shadow appears to be treading the video ground. And, as if her stage presence wasn’t enough, she is also a gifted storyteller. Even when Anderson tackles such serious issues as colonialism or the consequences of rampant capitalism in America, she manages to do it with lightness and humour, never forgetting the ultimate absurdity of life. And, therefore, of death too. So, if this is indeed the end of the world, we can be thankful that there is Anderson’s voice to put everything back into perspective, to make us laugh and reassure us. Delusion October 4-6 at 8pm Usine C http://usine-c.com/ 514.521.4493 Tickets: 40$ / Under 31 years old: 30$  Sasha Kleinplatz's Chorus Two..., photo by Celia Spenard-Ko Sasha Kleinplatz's Chorus Two..., photo by Celia Spenard-Ko À la sortie de Piss in the Pool, que retient-on cette année? Surtout Flotsam, la pièce de Leanne Dyer pour laquelle les cinq interprètes sont cachés sous d’imposants costumes composés de centaines de sacs de plastique. Trois grosses boules couleur vert menthe – les sacs du Supermarché PA – mais dont la couche s’avère être gracieuseté du Jean-Coutu, et deux chenilles de plastique, une blanche et l’autre noir (on se tient ici dans la palette limitée de Glad). C’est un défilé de mode, c’est un rituel consommateur, mais c’est surtout un petit monde étrange et aux images marquantes. On remarque aussi la rigueur que la chorégraphe Sasha Kleinplatz amène à tous ses projets avec Chorus Two… Après s’être entouré de femmes pour All the Ladies, c’est maintenant sur cinq hommes qu’elle projette son travail toujours très physique. Avec leurs complets noirs, les danseurs font penser à un Édouard Lock vidé de ses muses féminines. La New Yorkaise Shannon Gillen offre une introduction à la soirée qui nous plonge immédiatement dans un univers inquiétant avec WOLFMAN Redux. Le visage de la seule danseuse au fond de la piscine est recouvert de papier métallique. Son mouvement reflète le désarroi et l’anxiété que pourrait causer un manque d’oxygène. Ces trois pièces se retrouvent toutes en première partie, alors on peut deviner que la deuxième n’est pas tout à fait du même calibre. Toutefois, il y a Manuel Roque qui se démarque avec trou (pour deux) (à capella), un duo aux airs de compétition sadique qu’il danse avec Lucie Vigneault. Piss in the Pool 2011 18 juin à 20h30 Bain Saint-Michel, 5300 Saint-Dominique www.montrealfringe.ca 514.849.FEST (3378) Billets : 12$  Clap for the Wolfman, photo by Corrine Furman Imagine you’re a wolfman. At night, you’re traveling with a pack of wolves. Then, as soon as day breaks, they end up surrounding you. No longer one of their own, you have suddenly gone from friend to prey. Their teeth could pierce through your skin just as easily as you could pierce through a body made of balloons. Things can shift just as quickly in Clap for the Wolfman, a dance show by Shannon Gillen that the New York choreographer is presenting at the Fringe. Like night becomes day, the relationship between the five women performing can switch on a dime. Friendly one moment, they can be cold and even threatening the next. A woman with a long braid gets down to a two-piece black spandex suit that displays her athletic body in movement. Behind her, a life-size skeleton made of balloons imitates her. Two women sitting on the edge of the stage use microphones to create amplified sounds of the dancer’s moving body as they imagine them, turning the micro intro macro. The body is fragmented by the space between balloons, parts rather than whole. However, it is in partner work that Gillen excels. In duets, her dancers often become intertwined, forcing her to find creative solutions to the progression of their movement. In a playful section, performers pass a microphone around and, holding different positions, articulate their body into words. Her palm open and arm straight in front of her, a woman says, “This is me dancing in the 80s. This is me showing my wedding ring. This is me when I’m surrounded by wolves.” This exercise demands from the performers an awareness of their body in its present state at the same time as they must recall a body memory that overlaps it. They must consciously observe through their body how it organizes itself in relation to different external elements. Things don’t appear as light-hearted when a dancer hits planks of woods together. The lack of clear motivations behind her actions makes them look so senseless as to be menacing. The lighting might be the element that speaks the most to Gillen’s talents. Often, a single spot is used to light the entire stage from the front, so that the dancers’ monster shadows become a sinister backdrop. There is a tableau during which a performer holds the spot in her lap and shakes her unzipped hoodie on both sides of the light, making the shadows flicker like a stroboscopic television left on at night. I say that such details speak of Gillen’s talents because it reflects the choreographer’s ability to do a lot with little. Clap for the Wolfman is full of ingenious finds, from its use of light and sound to its choreography. Clap for the Wolfman June 15 at 10pm; June 17 at 6:45pm; June 18 at 8:45pm; June 19 at 3:15pm Tangente www.montrealfringe.ca 514.849.FEST(3378) Tickets: 12$  Tarek Halaby, Miguel Gutierrez & Michelle Boulée in Last Meadow, photo by Ian Douglas Tarek Halaby, Miguel Gutierrez & Michelle Boulée in Last Meadow, photo by Ian Douglas Last week, I was comparing Cindy Van Acker’s choreography to graphic design. This week, I couldn’t help but view Miguel Gutierrez’s Last Meadow through the lens of video art. It probably helps that, for this show, the New York choreographer is making extensive use of one of American cinema’s most iconic figures, James Dean. It is as if Gutierrez had taken images from East of Eden, Rebel Without a Cause, and Giant, and reedited them using video to deconstruct them. After emptying them of much of the narrative by using repetition and distorting the dialogue, he reconstructs the moving images with an emphasis on gestures, making them tip over into dance. The process also becomes about deconstructing the myth of America itself. While the performance is obviously a live one, Gutierrez predominantly uses coloured lighting (blue, red, purple, green, orange, pink) to flatten it into an image. It is as though he had dipped strips of films into dye to prevent any desire the viewer might have to see their image as realistic and to instead emphasize their cinematicness, their true nature as light filters and shapers. By taking these straightforward narratives and turning them into an experimental work, Gutierrez evidently obscures their meaning and makes Last Meadow more opaque, more difficult to penetrate. This is not a bad thing. As a recent viewing of Rebel Without a Cause reminded me, while the film deserves its status as a classic, it also suffers from the same faults as many other 1950s films. That is to say that it capitalizes excessively on dialogue, the characters making abundantly clear every single one of the psychological motivations for their behaviour. While they are tormented souls, there is no mystery clouding their characters. As a result, they are prevented from ever becoming full-fledged individuals and instead emerge as the mere result of causal relationships, the fatalistic product of their environment. However, in the absence of a clear narrative, nothing is so simple in Last Meadow. There is one more significant way in which Gutierrez tempers with his source of inspiration. While James Dean’s ambiguous sexuality has also made him a gay icon (no doubt helped by Sal Mineo’s character’s obvious crush on the star in Rebel), Gutierrez goes one step further in queering him. The role of Dean is played by Michelle Boulé, an Asian woman who won a Bessie Award for her performance. In turn, the role of Dean’s female lover is played by Tarek Halaby, a tall bearded man. As far as dance goes, he’s the one standing out, with his long straight legs that propel him into the air. For Gutierrez, who completes the love triangle in a Sal-Mineo-type character, they are not performing drag as much as acting like children playing dress up. As the three dancers perform a series of arbitrarily codified movements of their own making while taking off their clothes, Lost Meadow suddenly gains a feeling of freedom. The weight of the past, with the endless repetition of memories, is finally lifted… just as it persists as haunting echoes. Ultimately, Last Meadow proves to be a most rewarding experience. Last Meadow June 9 & 10 at 8pm; June 11 at 4pm Conservatoire d’art dramatique – Théâtre Rouge www.fta.qc.ca 514.844.3822 Tickets: 32$ / Under 31 & over 64 years old: 26$ Le corps technologique; le corps humain. C’est une tension qui s’est dessinée à Tangente la semaine dernière entre les propositions des chorégraphes Brian Brooks et Jacques Poulin-Denis. Deux visions du corps distinctes, mais dont la qualité de l’exécution révèle que des propos apparemment antagonistes peuvent tous deux tenir la route. Dans le hall d’entrée, projection de Rapid Still, un court métrage de Brooks. Il lui aura fallu plus de huit cents sauts pour produire moins de deux minutes au final. C’est que Brooks n’utilise que la fraction de seconde qu’il est suspendu dans les airs pour créer une vidéo où il flotte au-dessus du sol.  Gently Crumbling, photo d'Alexandre Pilon-Guay Gently Crumbling, photo d'Alexandre Pilon-Guay Même si cette utilisation de la technologie n’était point présente sur scène, on la sentait encore. C’est comme si Brooks s’était intéressé à assimiler la technologie dans le corps même. Résultat : I’m Going to Explode, court solo où un homme en complet s’agite au son de LCD Soundsystem. La musique contribue sûrement à l’effet vidéoclip, mais aussi le mouvement d’abord limité et répétitif qu’on dirait produit par une animation en stop motion. Mon côté minimaliste aimerait en fait voir une version où Brooks se limite à ce petit battement des bras tendus chaque côté de son corps pour les dix minutes que dure la pièce. C’était suivi d’un extrait de Descent, un travail de partenaire ingénieux où le corps de Brooks se transforme en boule de pinball contre celui d’Aaron Walter, dont les membres agissent comme des flippers qui fracturent son corps. Ils se retrouvaient pour un extrait de Motor (la technologie, je vous dis) où tous deux se déplacent à l'unisson… en sautillant sur une seule jambe pendant huit minutes. Encore là, on retrouve l’effet stop motion; on s’imagine Brooks créant cette chorégraphie pour vidéo, le pied des danseurs glissant au sol. C’est comme s’il s’imposait des contraintes numériques qu’il s’amusait ensuite à transposer au corps par le pouvoir de la créativité. Imaginatif et réussi. Cette numérisation du corps lui donne une dimension immortelle; il peut se défaire physiquement, mais ces séries de 0 et de 1 survivront, se multiplieront même. C’est tout autre chose dans la pièce de Poulin-Denis, comme on peut déjà le deviner d’après le titre, Gently Crumbling. Il s’agit là d’une comédie noire, d’un game show cruel, d’une expérience scientifique absurde. On l’aura deviné, il s’agit de l’existence humaine. C’est servi par trois interprètes magnifiques, Natalie Zoey-Gauld, Claudine Hébert, et Caroline Laurin-Beaucage, tour à tour concurrentes, cobayes, et travailleuses. Frédéric Wiper y trouve un rôle de soutien comme animateur, scientifique, et observateur. On tombe; on sonne la clochette. On fait la brouette jusqu’à ce que les bras ne tiennent plus et que notre visage se fasse glisser contre le sol; on sonne la clochette. On frappe une poupée gonflable ancrée au sol pour observer combien de fois elle vacillera avant de s’estomper. Autant de tâches pour révéler la futilité de la vie humaine. On peut bien faire de l’exercice, ça ne fait qu’à peine ralentir l’inévitable. « At this point in the procedure, » nous rappelle Zoey-Gauld, « time is of the essence. » On ramasse les biscuits soda éparpillés partout sur le sol, mais ils y retombent dans le vide de nos bras. C’est une course vers le rien, vers la mort. Alors on regarde cette poupée se dégonfler lentement. Ce n’est qu’une bébelle de plastique cheap. C’est ridicule. Et, je ne sais pas comment Poulin-Denis y parvient, c’est étrangement touchant. Tangente Jacques Poulin-Denis et son Grand Poney Brian Brooks et sa Moving Company |

Sylvain Verstricht

has an MA in Film Studies and works in contemporary dance. His fiction has appeared in Headlight Anthology, Cactus Heart, and Birkensnake. s.verstricht [at] gmail [dot] com Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed