She cut the stems and put the flowers in the vase at the centre of her heavy, wood kitchen table. When she was done, she would always take a step back and look at the arrangement, taking it in. Then, she would let it become part of the space in which she lived. She lived in a space of yellow flowers.

“They’re beautiful,” one of the ghosts said. “Aren’t they?” she replied. I should get some blue flowers tomorrow, she thought. That would be nice with the yellow flowers. At the market, she’d also picked up the freshest fruit she could find. She would spend the day making jam. She had a closet full of jars filled with preserves, for winter. When she was done, she made herself a cup of tea and brought it to the living room. She sat down on the couch, put her cup down on the coffee table, and picked up the book that was lying next to it. Across from her, a ghost was sitting in the armchair, reading a book of his own. She looked at him and, after a little while, when he was done a paragraph or a page, he looked up at her and smiled. She smiled back and began reading. They all sat down around the dining room table. They said grace, not because they were religious, but because they were thankful. At night, she would climb into her king size bed. She could hear the wind passing its hands through the weeping willow outside her bedroom window. Sometimes, it almost sounded like ocean waves. A ghost would always follow her into bed and wrap itself around her, so that she was always already dead, so that she would never worry about anything. Yes, tomorrow I will buy blue flowers, she thought.

0 Comments

The fire crackles. He’s sitting at the perfect distance where he can barely feel the heat, so that he is reminded of it every few seconds, every time it momentarily builds up, enveloping him. It’s only when it makes a sound, when a flame breaks a piece of the wood that he looks up and observes the fire for a moment. He always found beauty in anything that refuses to remain still, in anything that refuses to be captured.

His left hand moves to the side blindly. It doesn’t need to see; it knows where it’s going. It makes this movement every night, gently moving until it feels the warm ceramic in its grasp. His hand has become the shape of a cup. There is even a space in between his pinky and his ring finger, where the handle rests where no ring ever has. He takes a sip of the soothing tea as his eyes travel from the fire to the book he is reading, each word waiting for him. The door is barely open when his dog runs out like it’s been locked inside all winter. Its long blond hair hovers a centimetre above its skin in its excitement. The dog always remains just on the periphery of the man’s vision, ready to jump on anything that moves. Even if it were to chase a rabbit, it would always find its way back to the man, back to its home. For the man, these walks are an excuse to get out of the house, to enjoy the nature that surrounds it, the nature inside him. When he looks at a tree, he sees a more timeless version of himself. For him, it’s like watching a movie where nothing happens, the best movie ever made. Every morning, he makes the same breakfast: an egg fried in the fat from the bacon he cooked in the same pan, toasts, and fruit preserves. In the summer, it’s fresh fruit. He makes a pot of coffee as soon as he wakes up, though he only ever drinks one cup with his breakfast. The rest of the pot is merely for the smell. When he’s done, he sits at his desk and writes. He writes about the places he’s never been, the things he’s never done, the people he’s never met, the emotions he’s never felt. When he’s done for the day, he takes the pages and places them in a box. The only label the box has is the year that the given pages were written. It’s as arbitrary a way of labeling work as any other, he feels. When he dies, they’ll find the boxes and do what they want with their content. He won’t care. He’ll be dead. When he can no longer write, he follows the river into town, where he buys the little he needs. The walk takes him about thirty minutes. There, he has the only human interaction he has, outside of books and music. In the evening, he listens to the radio. This is all he does. He sits in his armchair – he sometimes wishes he would never get out of it – and he listens. Sometimes, he closes his eyes so he can hear better. Other times, he walks around the room so that the music can become his body, can move through him. If his arms float away from his torso, it means he’s dancing. At night, he climbs into bed with his book. When all is quiet, he can hear the waterfall softly murmuring outside his window. It’s the white noise he needs to stave off the anxiety of silence. He reads until his eyes close. Only then does his dog jump on the bed and lie down on his feet, keeping them warm. One day, his dog runs off and does not come back. That night, when he goes to bed, he feels the ghost he saw when he was seven years old climb into bed with him. The next morning, he does not wake up. The Moon and Sixpence (1919), W. Somerset Maugham

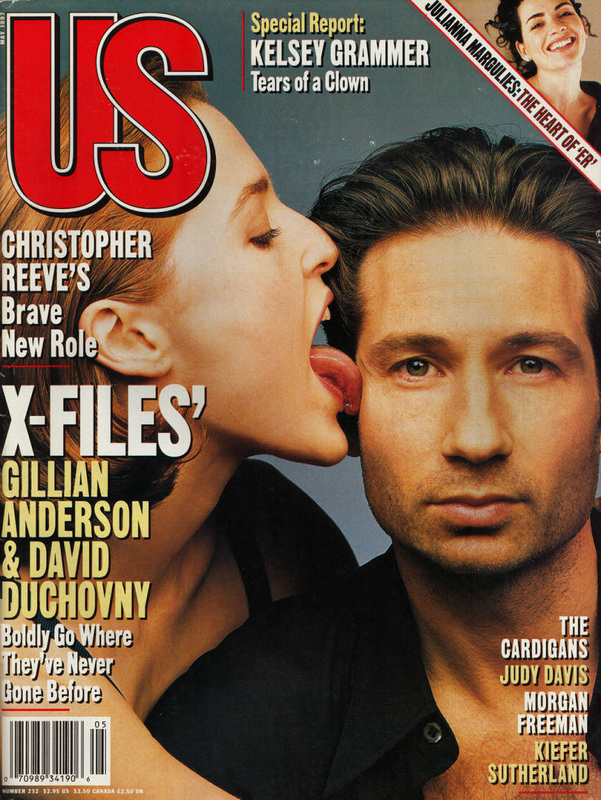

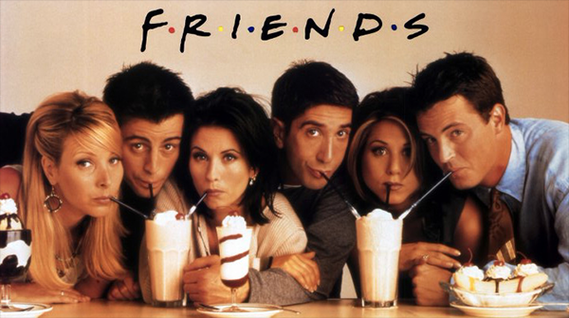

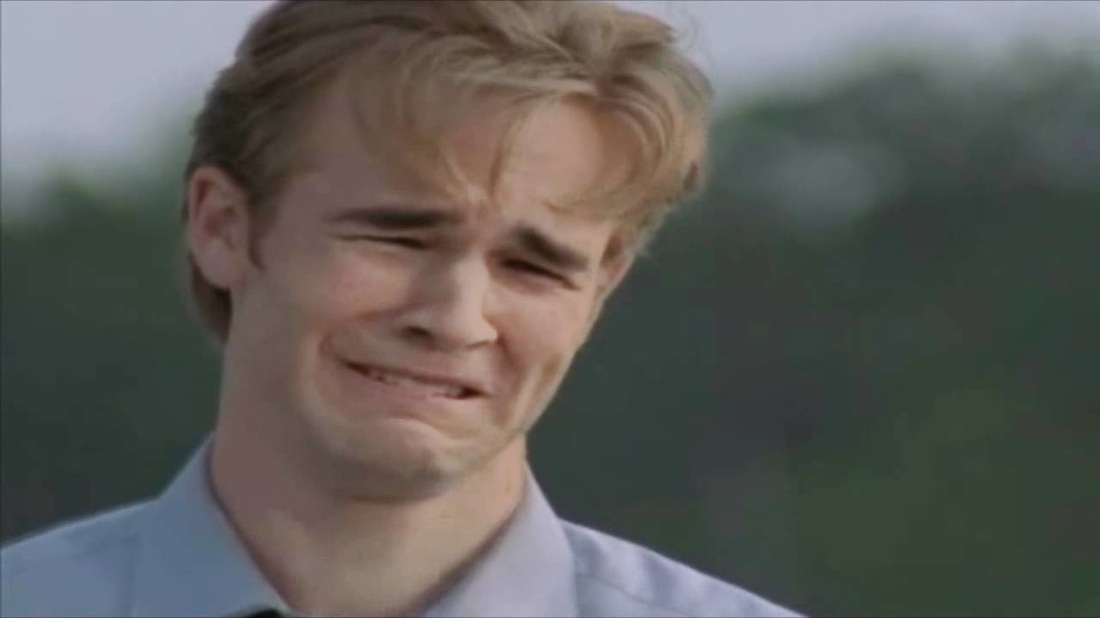

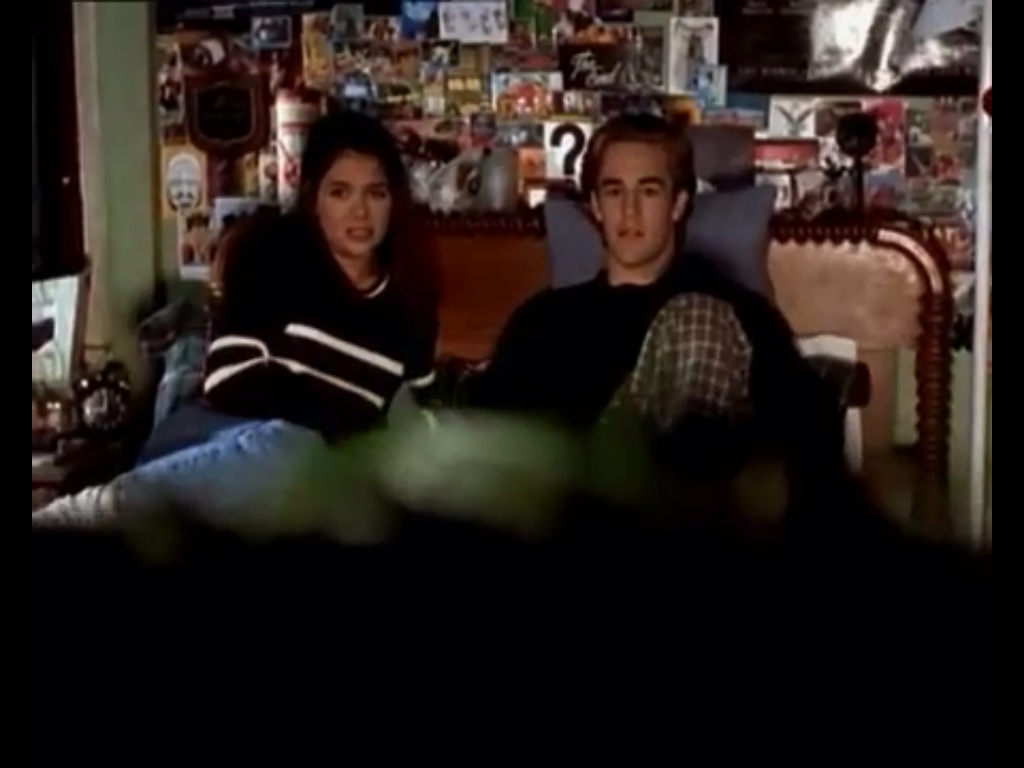

“I have an idea that some men are born out of their due place. Accident has cast them amid certain surroundings, but they have always a nostalgia for a home they know not. They are strangers in their birthplace, and the leafy lanes they have known from childhood or the populous streets in which they have played, remain but a place of passage. They may spend their whole lives aliens among their kindred and remain aloof among the only scenes they have ever known. Perhaps it is this sense of strangeness that sends men far and wide in the search for something permanent, to which they may attach themselves. Perhaps some deep-rooted atavism urges the wanderer back to lands which his ancestors left in the dim beginnings of history.” Solaris (1961), Stanislaw Lem “I didn’t believe for a minute that this liquid colossus, which had brought about the death of hundreds of humans within itself, with which my entire race had for decades been trying in vain to establish at least a thread of communication—that this ocean, lifting me up unwittingly like a speck of dust, could be moved by the tragedy of two human beings.” At the Vanishing Point: A Critic Looks at Dance (1973), Marcia B. Siegel “The rise in dance is also closely related to the dissolving of Puritanism in our society. Gradually we are getting rid of sex hangups and fear of our bodies; we’ve increased our respect for the nonverbal; nearly everyone has opened up to some form of consciousness-raising or lib or sensitivity movement. All of this has broken down the tacit resistance that many people had to dance. We know now that we need authentic human contact, however much it may disturb us or demand of us. The plastic world that we tried to make do has failed us badly, and we’re turning to what’s left of the earth. Dance, even when dressed in its richest costumes and most sophisticated techniques, never loses its connection with gut reality.” Les Mots pour le dire (1975), Marie Cardinal « La rencontre avec mes premiers vrais défauts me donnait une assurance que je n'avais jamais eue. Ils mettaient en valeur mes qualités que je découvrais aussi et qui m'intéressaient moins. Mes qualités ne me faisaient progresser que lorsque mes défauts les excitaient. [...] Je ressentais profondément qu'en les connaissant ils devenaient des outils utiles à ma construction. Il ne s'agissait plus de les repousser, ou de les supprimer, encore moins d'en avoir honte, mais de les maîtriser et de m'en servir, le cas échéant. Mes défauts étaient des qualités, en quelque sorte. » A Choreographer’s Handbook (2010), Jonathan Burrows “We are told that dance is a minority art form loved only by a few, and yet there are many of us who feel passionate about this thing. Here is my fantasy: perhaps the number of people who like dance performances is the right number?” Testament (2012), Vickie Gendreau « Je suis en manque de nicotine. Je suis en manque de quiétude. Il va toujours me manquer quelque chose pour être heureuse. De temps, ultimement. » I am interested in language because it wounds or seduces me. –Roland Barthes “Tapette” is the French equivalent of “faggot”, though it actually means “swatter”, so “limp-wristed” would be closer to its meaning. “Tapette” is the word teens at my school would use to hurt me. I grew up on a dairy farm in Lacolle, a Quebec country town that shares a border with New York State. It might however be more accurate to say that I grew up on television, movies, books, and music. In elementary school, I started looking through the TV guide and selecting the shows I wanted to watch, making myself a schedule for the year. The minute I would get home from school, I would turn the TV on and watch it until it was time to go to bed. One day, while flipping channels, I came across an English TV show. I still remember what I saw that day. A little girl was dragging a blanket down a hallway and knocked on the door of the bedroom she was sharing with her older sister, but for some reason her sister wouldn’t let her in, so the little girl simply lied down on her blanket in the hallway. When her sister finally opened the door, the little girl was already asleep on her blanket, so her sister dragged her into the bedroom by pulling on it. I laughed. Even though I didn’t understand English, I understood what had happened. I started watching Full House reruns every day. Over time, my ear grew accustomed to the language and I started picking up words here and there based on repetition and visual cues. Then sentences. Then entire episodes. One of my friends later made fun of me, saying I learned English because of my attraction to John Stamos. She might be right. From then on, I only watched television in English: Roseanne, Baywatch, Beverly Hills, 90210, The X-Files, Ellen, My So-Called Life, Friends, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Ally McBeal, Dawson’s Creek, Will & Grace… It was refreshing. Quebec television doesn’t have much in the way of means, so screenwriters have characters scream at each other in a desperate attempt to create drama. On American television, other things could happen: characters could be funny, sexy, endearing, strange, relatable, human. By the time I was fifteen, I would only watch American movies in their original language. Our senior year, my best friend Emilie and I would rent slashers on Friday nights and watch them together. It was my way of emulating Dawson and Joey in Dawson’s Creek. My reading followed suit. In 1995, I bought Ellen DeGeneres’s first book in English because that was the only option. The following year, I began reading Stephen King’s The Green Mile, which was released in six monthly installments. When I showed up at the bookstore and they’d only received part 3 in English, I bought it instead of waiting for the French translation. The English section at the bookstore in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu was in the back corner, only about a meter wide. The selection could best be described as what one finds at the average airport bookstore. Still, when I look back on those years, one of the few good memories I can muster is reading the latest John Grisham by the pool. I’ve repressed much of my high school years, but otherwise I do recall crying myself to sleep many nights and being suicidal. I remember something else. For Valentine’s Day, students could send each other gifts through internal mail. Gifts were delivered during class and, in order to get one’s gift, one had to perform a task chosen by the sender. When I showed up to school one morning after having missed the previous day because I was sick, a friend told me they’d come to deliver a gift for me the day before. I must have felt something was up because I asked all my friends if they were the ones who’d sent me the gift. They all said no. Later that day, the delivery service showed up to my French class. They said that, to get my gift, I had to sing, “Je m’appelle Paulette / Je suis une tapette” (My name is Paulette / I am a faggot). In what was an unusual moment, I stood up for myself and told them I wouldn’t. They didn’t know what to do. No one had ever refused a gift before. The teacher supported me, saying that she didn’t think it was funny either. They said they were willing to give me the gift anyway. I told them I didn’t want it. They said they knew what it was, that it was nothing bad. I wish I’d kept standing up for myself, but I caved. The gift was nothing bad, but it was clearly just an excuse to get me to say I was a faggot: a granola bar and bits of an eraser. I chose to go to cegep in English. I told myself it was to master the language but, in retrospect, it was clearly to escape my milieu. There, I gave up reading in French entirely. Not knowing anybody when I first started school, I would go to the library whenever I had free time between classes. There, I read A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Notes from Underground. Because of my Canadian Literature class, I even ended up reading Michel Tremblay’s The Fat Woman Next Door Is Pregnant in English. Then I did a BA in Communication Studies and English Literature at Concordia University, where I read Flaubert, Baudelaire, and Mallarmé in English, where I read about Quebec cinema in English. I went to McGill University for half a second, where I read Camus and Foucault in English. Then I went back to Concordia to do an MA in Film Studies, where I read Barthes in English and read about Quebec cinema some more, in English. I also started writing dance reviews. In English. When I graduated from the master’s program in 2011, I realized I no longer had any clue what French people were reading. I decided that I would from then on alternate between French and English books. I asked the few francophone friends I had left for recommendations. In February of the same year, I went to see choreographer Susanna Hood’s Costing Not Less Than Everything with the intention of reviewing it. In the piece, dancer Holly Bright stands naked and, as soon as the light from the projectors hits her body, she crashes to the floor. She attempts to get back up, but her arms, crooked, refuse to cooperate. And I was back in second grade. There was a pedagogue who’d come in our classroom to introduce herself. She was using crutches. She explained that, when she was a baby, she lacked oxygen and, as a result, she needed crutches to walk. One day, a boy was running after his friend down the hallway and the pursued boy ran around a corner, never having the chance to see that the pedagogue was right there, slamming into her before either knew what was happening, her crutches sliding against the floor until they were no longer touching it, her body crashing against the floor, the young boy frozen, all of us frozen, except for her, struggling to get up, failing to get up. Our little children bodies felt powerless. When I finally saw a teacher walking down the hall to help her, I was able to breathe again. She grabbed his arm and stood back up, and in her eyes I could see the tears she was fighting to hold back. It still hurts thinking about it over twenty-five years later. The review of the dance show would only come out in French. So I wrote it in French, even though I was writing for an English website at the time. In 2012, I was accepted to go to the Biennales Internationales du Spectacle in Nantes with the Quebec delegation of young professionals. I was excited to go to Europe for the first time, but also worried about spending the week with fifteen French-speaking individuals. The last time I had done that was in high school. I was afraid I wouldn’t know how to relate to them. But it went well. One night, when I came back to my hotel room, I found the man I was sharing the room with lying in bed watching a French-dubbed episode of Dawson’s Creek. “It’s funny,” he told me, “I turned the TV on and it was the episode a song I worked on played in. I still get money for it from time to time.” When I came back to Montréal, I made a conscious decision to listen to more French music. Maybe it’s no coincidence that the first genre that struck a chord with me was black metal (Gris, Forteresse, Sui Caedere, Sombres forêts), with its vocals abstracted beyond recognition. Black metal felt like the colour of my soul. Then the darkness of minimal synth also won me over (Automelodi, Police des moeurs, Xarah Dion, Essaie pas). In 2013, I was asked to join a French cultural radio show as their dance critic. I’d wanted to get involved in radio for some years, but the thought of expressing myself in French scared me. Luckily, I tend to take fear as a sign that I should do whatever terrifies me, so I said yes. A few years ago, a man I fooled around with showed me a picture of his friend’s Halloween costume. Her long brown hair was frizzy. She simply applied some makeup to create dark circles under her eyes. She was “dressed” as Québec rocker Gerry Boulet. I was aware that if you showed this picture to anyone who’s not French Québécois, all you’d get is a blank stare; yet I was laughing so hard that I had trouble standing up. That’s when I realized that Québec culture is one big inside joke. Like all cultures. This was further demonstrated to me when I attended my first Total Crap, a screening event put on by Simon Lacroix and Pascal Pilote, two fans of the worst that television and cinema have to offer. Given that they are based in Montréal, a lot of what they get their hands on was produced in Québec. I’ve never felt prouder of my culture than I did when I was surrounded by people laughing at it with me. This year, I stopped talking about dance on the radio because listening to myself was painful. I was struggling with the language. Someone on Twitter recently claimed that French sounds like it’s in cursive, but that’s not my experience. Each word is like a heavy building block I have to drag out of myself and put one after another to form a sentence. It’s the language that was used to hurt me and still today I can feel a burning tightness in my chest whenever I attempt to use it. English is the language I used to escape, to medicate myself, and I developed an addiction to it. When I speak English, I feel like I’m reading from a script, like I don’t even have to think about what I’m saying because somebody else wrote it for me. I don’t believe that Québec is somehow worse than anywhere else. I’m aware that teenagers are assholes everywhere. If I’d grown up in an English environment, I probably would have gone to a French cegep and become a Francophile.

I now live in Petit Laurier, the Montréal neighbourhood also known as Petite France due to its high concentration of French immigrants. After having gone through all of the gay Anglophone Montrealers who would have me, I’m now with my first Québécois boyfriend. Most of the time, I speak to him in English. The first movies I remember seeing as a kid are slashers. My mom and my aunt (who was only called so by my brothers and me because she was a close friend of the family) were both fans of horror films. I grew up in the eighties, when the slasher genre was at its height: eight Friday the 13th movies, five Nightmares on Elm Street, four Halloweens. When the Gulf War began, the first one, I was nine years old. The phrase “World War III” was being thrown around by the media, as it tends to be in a world that likes nothing more than to cash in on previous successes with a much-anticipated sequel. I thought the end of the world was coming right to our doorstep in Lacolle, a small Quebec town mostly known for its customs since it shares a border with New York State. I did the only thing that made sense to me at the time: I put my favourite things in a cardboard box in my closet so I could grab it in case we had to leave in a hurry. All I remember putting in it were Legos. In my head, the plan was that my family would escape to the Laurentian Mountains – a mere four-hour drive from Lacolle – where we would live by a lake, humbly eating finger sandwiches and playing cards to entertain ourselves while patiently waiting for the rest of the world to kill each other. My apocalyptic world looked like a bucolic family picnic. Things took a turn for the worse in junior high when I discovered that the cruelty of others was not limited to images of war on television and that the enemy did not always easily identify himself by wearing camo. As a trumpet player, I joined the school’s orchestra, which required staying after school twice a week and taking a later bus. While I was waiting for the bus on the very first evening, a student I didn’t know threatened to beat me up for no apparent reason. The story I told myself was that he was frustrated because he had had to stay for detention. It was the last time I took the later bus. I made up a now long-forgotten excuse for my mother as to why I could no longer take it. From then on, she would come and pick me up twice a week after orchestra practice, a one-hour round-trip. In high school, verbal bullies figured out I was gay before I did because their survival didn’t depend on denial, but also partially because there wasn’t a single guy at my school worth crushing on. They were years of crying myself to sleep, my mother visibly worried by my tears. What she or anyone else didn’t and still doesn’t know is what I would sometimes do when home alone. I would take a sharp knife and lie down with my back against the floor. I would hold the knife above my chest with both hands and swiftly bring it down, stopping it just before it would pierce my skin. Every time I brought down the knife, in that fraction of a second, I would decide whether it would go all the way. No. Not yet. After a few near stabs, I would stand up and put the knife back in the kitchen drawer, until the next time I needed to feel better. Years later, while looking through my high school yearbook, in between typically generic sentences, I came across a singular one handwritten by my drama teacher: “I am no longer worried.” Surely I had read the note before, but it didn’t register until then what it meant. In my last year of high school, my best friend Emilie and I started a new tradition because of Dawson’s Creek: every Friday night, we would rent slashers at the video store and watch them at her house. I envied Emilie because her mother brought her to Montreal to see West Side Story when the show came to the city. A few years ago, I learned through my mother that Emilie had died shortly after giving birth to a daughter, her first child. By then, we had lost touch. I still have the pictures I took of her for a photography class in college. Inspired by slashers, the series has Emilie holding a knife to defend herself against Jason or Freddy or Michael. In one of the pictures, she is lying with her hands resting on her stomach, her eyes closed under a glass coffee table, a make-shift coffin. Once your high school best friend has passed away, there is no longer any reason to believe that you are too young to die. In college, I studied cinema. I still had a soft spot for the first movies I remembered seeing as a child. When came the time to write about slashers, I pondered the source of my attraction to them. To me, they were more exciting than they were scary. I realized that slashers made everything simple: no matter the weight of the world on your shoulders, when a knife-yielding psycho-killer comes after you, you run. In spite of appearances, slashers weren’t about death; they were about life. Every time a person runs, without even thinking, they are saying yes to life, in spite of everything. The movies that most move me are about mortality and, throughout university, I often returned to the theme. I wrote about Agnès Varda’s Cléo de 5 à 7, in which a singer wanders through the streets of Paris while she waits to find out if she has cancer, on at least three different occasions. As Cléo finally faces her inevitable end – cancer or not – she transforms from an object for the gaze of others to a subject with her own life force. She becomes alive. I too wanted to become alive, which meant always being on the verge of death. “Should I kill myself, or have a cup of coffee?” This quote is often attributed to Albert Camus, though there are no records of him ever having written or even said it. All the same, it is a question I am constantly asking myself. So far, I have always chosen the coffee. The subject now seeps into my fiction. In a year when I was in dire need of a better world, I wrote a series of short stories, all highly personal utopias, as utopias always are. Recurring themes included home, food, art, bodies of water, turtles, solitude, love and – yes – death. Despite the brevity of the stories and the low number of characters, five of them still managed to meet their fate, all in the most utopic ways, of course.

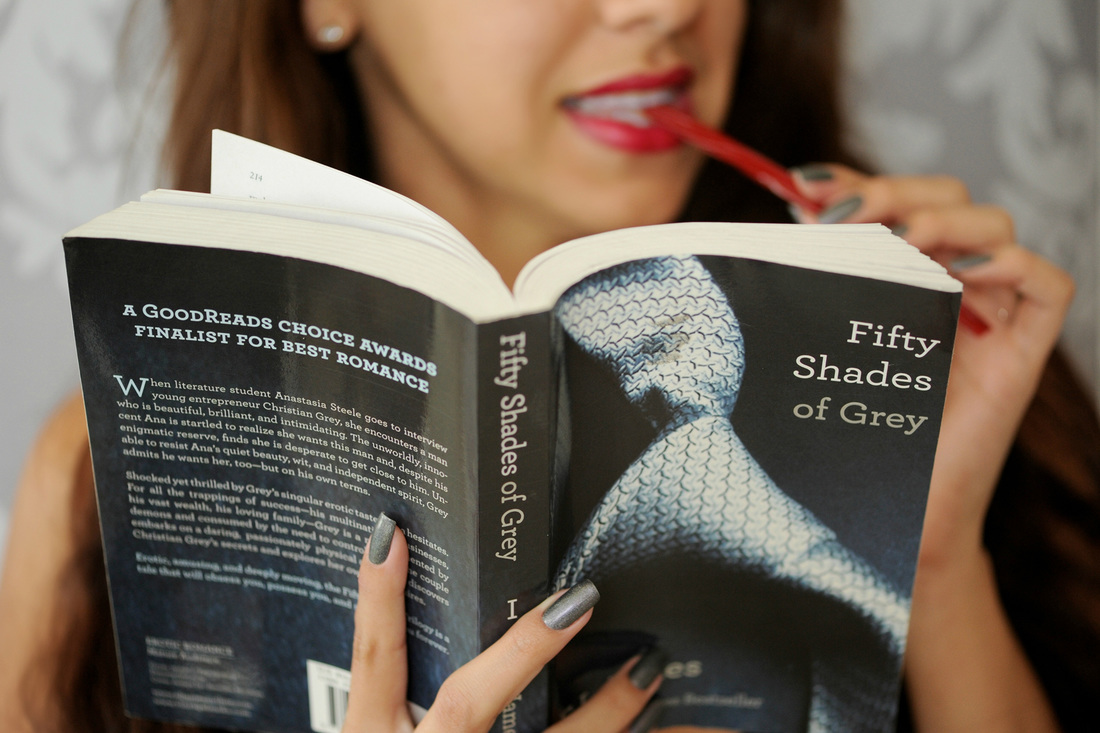

I am now simultaneously closer to and further from my death than I was in high school. Today, like every other day, I ask myself if I will finally bring the knife all the way down. No. Not yet. Depuis 2008, je suis membre de Goodreads, un site web où maintenant plus de 20 millions d’usagers peuvent répertorier les livres qu’ils veulent lire et qu’ils ont lus, les coter, les critiquer, en discuter. Ils peuvent aussi créer différentes listes où tous les membres peuvent voter pour leur livre préféré ou celui qu’ils détestent le plus, tout dépendant de la catégorie. J’ai remarqué que les listes contenant le roman érotique Fifty Shades of Grey d’E.L. James portent les meilleurs titres. Pour votre plus grand plaisir, j’ai traduit ces titres en tentant d’être le plus fidèle possible aux originaux. Au diable, syntaxe et grammaire!

Meilleure romance érotique homme/femme comme Fifty Shades of Grey (pas paranormale, pas d’école secondaire, pas gai, pas de science-fiction) Hommes dominants/sexy/possessifs Hommes fictifs qui vous font tortiller… de la bonne façon ;) Meilleur tomber en amour avec un millionnaire / milliardaire / roi / homme riche JE SUIS EN AMOUR!!! Est-ce que c’est juste moi? Livres que vous n’avez pas aimés que tout le monde semble aimer Les mauvais garçons rencontrent les vierges Donc vous aimez un mauvais garçon ou un héros torturé Livres dont vous êtes fatigués d’entendre parler Je comprends pas pourquoi on en fait toute une histoire Les hommes romantiques les plus possessifs Dealbreakers : si vous aimez ce livre, on va pas bien s’entendre Héros romantiques dominants-alpha de tous les temps Meilleurs livres de baise perverse JE L’AI LU ET RELU! Livres qui vous font vraiment chier Livres schmexy qui valent la peine d’être lus Personnages masculins desquels vous vous enfuiriez s’ils essayaient de sortir avec vous Parler cochon à son meilleur Meilleures romances dysfonctionnelles Alphas douteux : dominants, possessifs, jaloux, autoritaires, parfois terrifiants, mais toujours hots. À vous faire tomber les petites culottes Des vrais mâles alphas qui ne PARTAGENT pas leurs femmes. Vous aimez les histoires cochonnes, mais vous n’aimez pas les vampires? I don’t care about your professional dramas. I’m not interested in your fantasy of a job. I’m not interested in finding out how you’re going to solve a crime with methods that don’t exist. I’m interested in the fantasy of human relationships. I want to believe in reciprocity. I want to believe that we’re going to get together in the last season.

Unfortunately, my life has already lasted more than seven seasons. Everyone agrees that my life used to be much better in its earlier years, that we should have quit years ago, that – as the only original member of the cast left – I really should move on. I’m just waiting for you to return so the show can end the way it’s supposed to end. Then we’ll pull the plug. That’s how you get happily ever after. Au cours d’un an, je suis mort cinquante-deux fois. Ce qui suit est le dernier

de douze échantillons des traces écrites laissées par ces cinquante-deux morts. Aujourd’hui je meurs Mais ce n’est que mon égo Qui meurt : je ne vous laisse Rien Que toute chose Qui de la vie En vie D’étoile En fleur Et tout Le reste Aujourd’hui je meurs Trouverez-vous Mon cadavre beau? Penserez-vous : il aurait dû Être aimé? Aujourd’hui je meurs Ici ou ailleurs Peu importe Chez moi n’est pas Lieu ou famille Chez moi est amour Chez moi est Dans ma tête : ici ou ailleurs Aujourd’hui je meurs Pense à moi Et je ne serai pas Seul Au cours d’un an, je suis mort cinquante-deux fois. Ce qui suit est le onzième

de douze échantillons des traces écrites laissées par ces cinquante-deux morts. Aujourd’hui je meurs Je suis toujours Près, mais jamais Prêt; il n’y aura Jamais assez d’amour Pour remplir l’espace Inexistant entre moi et la mort Aujourd’hui je meurs Et dès lors Je n’ai plus besoin De vous Quel soulagement J’aurais dû Vous tuer il y a longtemps Aujourd’hui je meurs Enfin Si seulement J’avais pu Toujours mourir Je n’aurais jamais Eu à m’inquiéter De rien Aujourd’hui je meurs Du moment Que je l’accepte Plus rien Plus de mal Plus de douleur Plus du tout Rien Que la respiration Que la drogue Que le post-tout Au cours d’un an, je suis mort cinquante-deux fois. Ce qui suit est le dixième

de douze échantillons des traces écrites laissées par ces cinquante-deux morts. Aujourd’hui je meurs Je l’ai rencontré Il existe On peut mourir En paix Aujourd’hui je meurs Ta main Sur mon avant-bras, Ton avant-bras Sur ma main : pull Aujourd’hui je meurs Irradiez Toutes les distances Fumez tout Mangez tout Jusqu’à ce que vos doigts Tentaculaires transpercent ma peau Je ne suis plus Solide, ma peau Ne brisera pas; Au bout de vos doigts : la lumière Aujourd’hui je meurs Redonnez -le moi. Vous Me le devez. Vous me le devez Pour toutes les absences. On ne peut Offrir à un homme Qu’un dernier repas. Il faut Lui donner chaque dernière chose Jusqu’à ce que mort S’ensuive. Aujourd’hui je meurs Testament : Les autres Savent tout. Donnez-lui Tous mes écrits; dites-lui Que Chaque Mot Est Pour Lui, rétroactivement et à perpétuité, Jusqu’à ce que mort s’ensuive. |

Sylvain Verstricht

has an MA in Film Studies and works in contemporary dance. His fiction has appeared in Headlight Anthology, Cactus Heart, and Birkensnake. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed