|

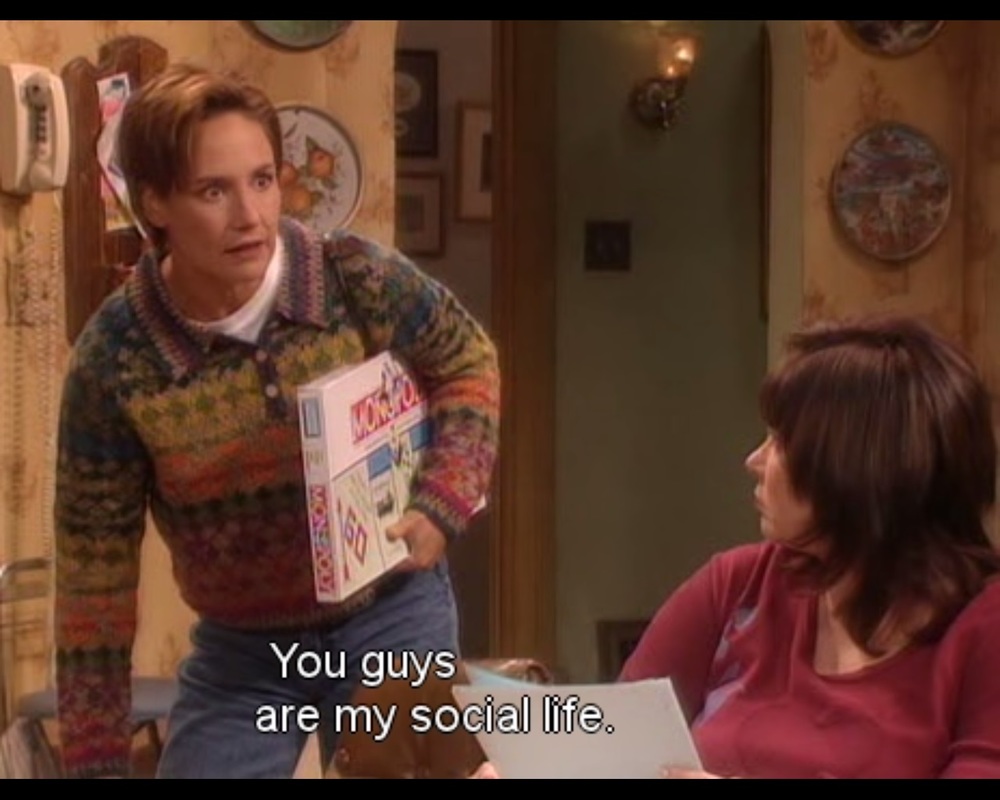

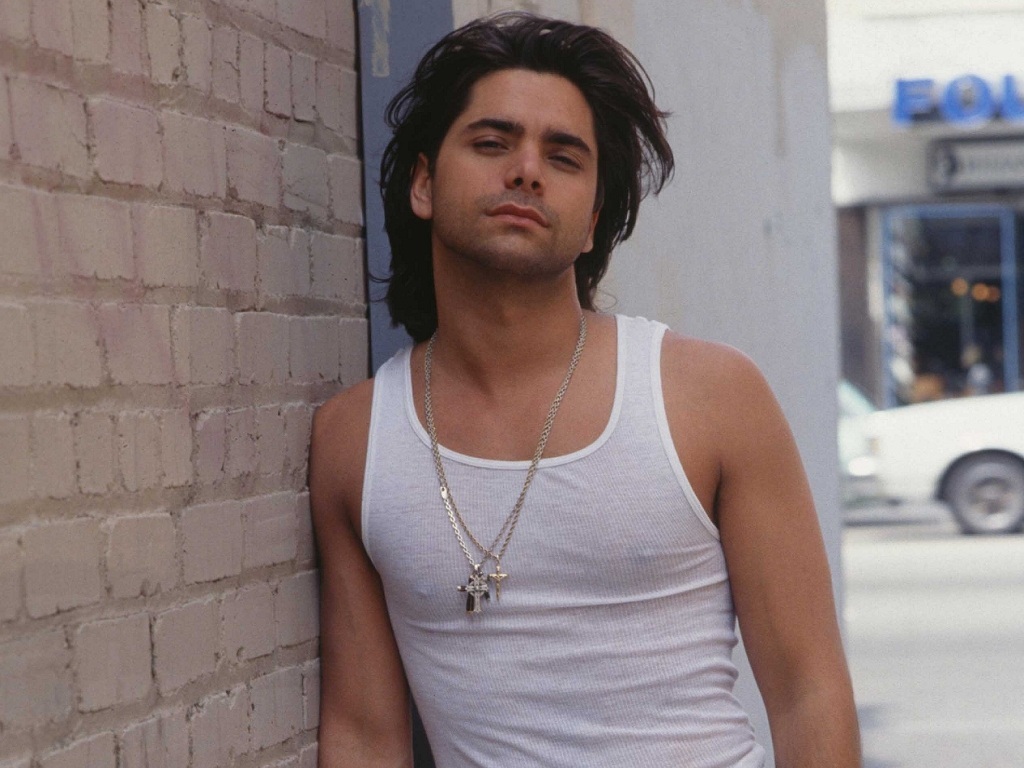

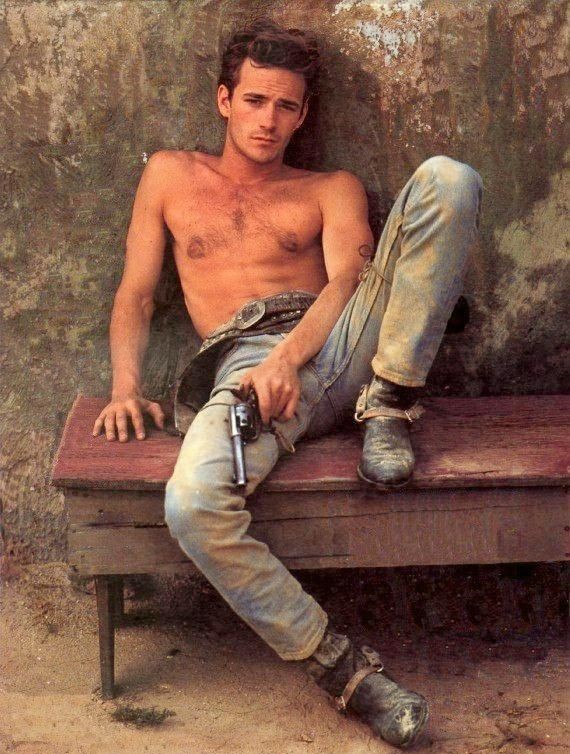

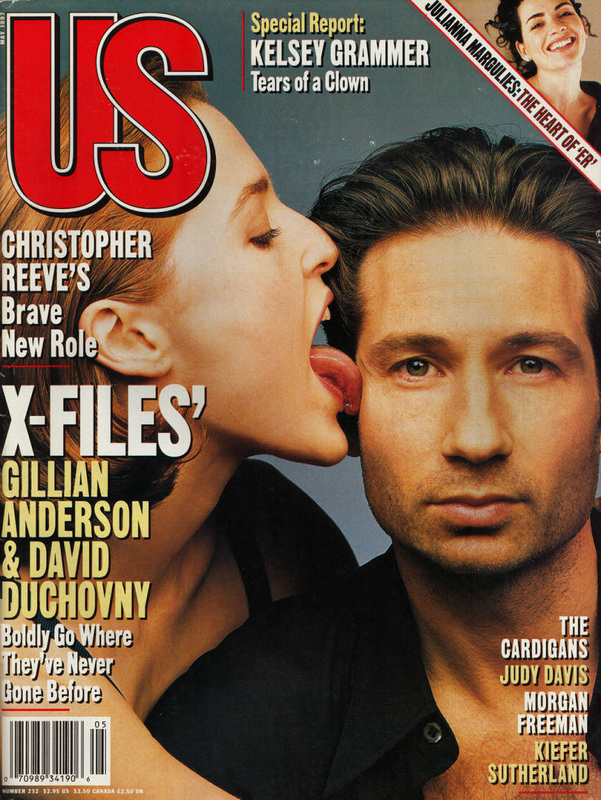

I am interested in language because it wounds or seduces me. –Roland Barthes “Tapette” is the French equivalent of “faggot”, though it actually means “swatter”, so “limp-wristed” would be closer to its meaning. “Tapette” is the word teens at my school would use to hurt me. I grew up on a dairy farm in Lacolle, a Quebec country town that shares a border with New York State. It might however be more accurate to say that I grew up on television, movies, books, and music. In elementary school, I started looking through the TV guide and selecting the shows I wanted to watch, making myself a schedule for the year. The minute I would get home from school, I would turn the TV on and watch it until it was time to go to bed. One day, while flipping channels, I came across an English TV show. I still remember what I saw that day. A little girl was dragging a blanket down a hallway and knocked on the door of the bedroom she was sharing with her older sister, but for some reason her sister wouldn’t let her in, so the little girl simply lied down on her blanket in the hallway. When her sister finally opened the door, the little girl was already asleep on her blanket, so her sister dragged her into the bedroom by pulling on it. I laughed. Even though I didn’t understand English, I understood what had happened. I started watching Full House reruns every day. Over time, my ear grew accustomed to the language and I started picking up words here and there based on repetition and visual cues. Then sentences. Then entire episodes. One of my friends later made fun of me, saying I learned English because of my attraction to John Stamos. She might be right. From then on, I only watched television in English: Roseanne, Baywatch, Beverly Hills, 90210, The X-Files, Ellen, My So-Called Life, Friends, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Ally McBeal, Dawson’s Creek, Will & Grace… It was refreshing. Quebec television doesn’t have much in the way of means, so screenwriters have characters scream at each other in a desperate attempt to create drama. On American television, other things could happen: characters could be funny, sexy, endearing, strange, relatable, human. By the time I was fifteen, I would only watch American movies in their original language. Our senior year, my best friend Emilie and I would rent slashers on Friday nights and watch them together. It was my way of emulating Dawson and Joey in Dawson’s Creek. My reading followed suit. In 1995, I bought Ellen DeGeneres’s first book in English because that was the only option. The following year, I began reading Stephen King’s The Green Mile, which was released in six monthly installments. When I showed up at the bookstore and they’d only received part 3 in English, I bought it instead of waiting for the French translation. The English section at the bookstore in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu was in the back corner, only about a meter wide. The selection could best be described as what one finds at the average airport bookstore. Still, when I look back on those years, one of the few good memories I can muster is reading the latest John Grisham by the pool. I’ve repressed much of my high school years, but otherwise I do recall crying myself to sleep many nights and being suicidal. I remember something else. For Valentine’s Day, students could send each other gifts through internal mail. Gifts were delivered during class and, in order to get one’s gift, one had to perform a task chosen by the sender. When I showed up to school one morning after having missed the previous day because I was sick, a friend told me they’d come to deliver a gift for me the day before. I must have felt something was up because I asked all my friends if they were the ones who’d sent me the gift. They all said no. Later that day, the delivery service showed up to my French class. They said that, to get my gift, I had to sing, “Je m’appelle Paulette / Je suis une tapette” (My name is Paulette / I am a faggot). In what was an unusual moment, I stood up for myself and told them I wouldn’t. They didn’t know what to do. No one had ever refused a gift before. The teacher supported me, saying that she didn’t think it was funny either. They said they were willing to give me the gift anyway. I told them I didn’t want it. They said they knew what it was, that it was nothing bad. I wish I’d kept standing up for myself, but I caved. The gift was nothing bad, but it was clearly just an excuse to get me to say I was a faggot: a granola bar and bits of an eraser. I chose to go to cegep in English. I told myself it was to master the language but, in retrospect, it was clearly to escape my milieu. There, I gave up reading in French entirely. Not knowing anybody when I first started school, I would go to the library whenever I had free time between classes. There, I read A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Notes from Underground. Because of my Canadian Literature class, I even ended up reading Michel Tremblay’s The Fat Woman Next Door Is Pregnant in English. Then I did a BA in Communication Studies and English Literature at Concordia University, where I read Flaubert, Baudelaire, and Mallarmé in English, where I read about Quebec cinema in English. I went to McGill University for half a second, where I read Camus and Foucault in English. Then I went back to Concordia to do an MA in Film Studies, where I read Barthes in English and read about Quebec cinema some more, in English. I also started writing dance reviews. In English. When I graduated from the master’s program in 2011, I realized I no longer had any clue what French people were reading. I decided that I would from then on alternate between French and English books. I asked the few francophone friends I had left for recommendations. In February of the same year, I went to see choreographer Susanna Hood’s Costing Not Less Than Everything with the intention of reviewing it. In the piece, dancer Holly Bright stands naked and, as soon as the light from the projectors hits her body, she crashes to the floor. She attempts to get back up, but her arms, crooked, refuse to cooperate. And I was back in second grade. There was a pedagogue who’d come in our classroom to introduce herself. She was using crutches. She explained that, when she was a baby, she lacked oxygen and, as a result, she needed crutches to walk. One day, a boy was running after his friend down the hallway and the pursued boy ran around a corner, never having the chance to see that the pedagogue was right there, slamming into her before either knew what was happening, her crutches sliding against the floor until they were no longer touching it, her body crashing against the floor, the young boy frozen, all of us frozen, except for her, struggling to get up, failing to get up. Our little children bodies felt powerless. When I finally saw a teacher walking down the hall to help her, I was able to breathe again. She grabbed his arm and stood back up, and in her eyes I could see the tears she was fighting to hold back. It still hurts thinking about it over twenty-five years later. The review of the dance show would only come out in French. So I wrote it in French, even though I was writing for an English website at the time. In 2012, I was accepted to go to the Biennales Internationales du Spectacle in Nantes with the Quebec delegation of young professionals. I was excited to go to Europe for the first time, but also worried about spending the week with fifteen French-speaking individuals. The last time I had done that was in high school. I was afraid I wouldn’t know how to relate to them. But it went well. One night, when I came back to my hotel room, I found the man I was sharing the room with lying in bed watching a French-dubbed episode of Dawson’s Creek. “It’s funny,” he told me, “I turned the TV on and it was the episode a song I worked on played in. I still get money for it from time to time.” When I came back to Montréal, I made a conscious decision to listen to more French music. Maybe it’s no coincidence that the first genre that struck a chord with me was black metal (Gris, Forteresse, Sui Caedere, Sombres forêts), with its vocals abstracted beyond recognition. Black metal felt like the colour of my soul. Then the darkness of minimal synth also won me over (Automelodi, Police des moeurs, Xarah Dion, Essaie pas). In 2013, I was asked to join a French cultural radio show as their dance critic. I’d wanted to get involved in radio for some years, but the thought of expressing myself in French scared me. Luckily, I tend to take fear as a sign that I should do whatever terrifies me, so I said yes. A few years ago, a man I fooled around with showed me a picture of his friend’s Halloween costume. Her long brown hair was frizzy. She simply applied some makeup to create dark circles under her eyes. She was “dressed” as Québec rocker Gerry Boulet. I was aware that if you showed this picture to anyone who’s not French Québécois, all you’d get is a blank stare; yet I was laughing so hard that I had trouble standing up. That’s when I realized that Québec culture is one big inside joke. Like all cultures. This was further demonstrated to me when I attended my first Total Crap, a screening event put on by Simon Lacroix and Pascal Pilote, two fans of the worst that television and cinema have to offer. Given that they are based in Montréal, a lot of what they get their hands on was produced in Québec. I’ve never felt prouder of my culture than I did when I was surrounded by people laughing at it with me. This year, I stopped talking about dance on the radio because listening to myself was painful. I was struggling with the language. Someone on Twitter recently claimed that French sounds like it’s in cursive, but that’s not my experience. Each word is like a heavy building block I have to drag out of myself and put one after another to form a sentence. It’s the language that was used to hurt me and still today I can feel a burning tightness in my chest whenever I attempt to use it. English is the language I used to escape, to medicate myself, and I developed an addiction to it. When I speak English, I feel like I’m reading from a script, like I don’t even have to think about what I’m saying because somebody else wrote it for me. I don’t believe that Québec is somehow worse than anywhere else. I’m aware that teenagers are assholes everywhere. If I’d grown up in an English environment, I probably would have gone to a French cegep and become a Francophile.

I now live in Petit Laurier, the Montréal neighbourhood also known as Petite France due to its high concentration of French immigrants. After having gone through all of the gay Anglophone Montrealers who would have me, I’m now with my first Québécois boyfriend. Most of the time, I speak to him in English.

0 Comments

|

Sylvain Verstricht

has an MA in Film Studies and works in contemporary dance. His fiction has appeared in Headlight Anthology, Cactus Heart, and Birkensnake. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed