|

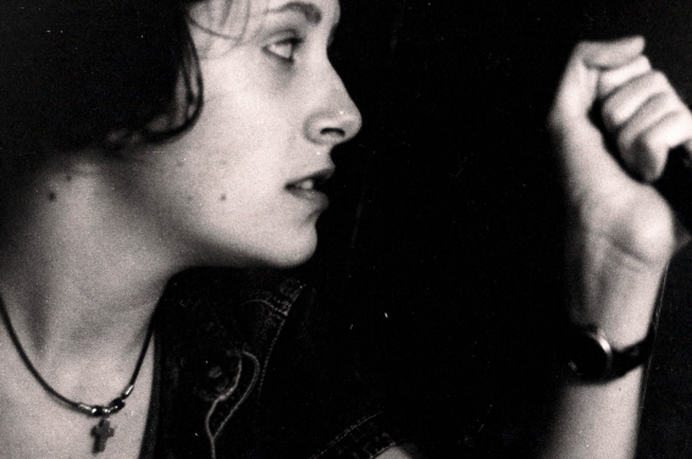

The first movies I remember seeing as a kid are slashers. My mom and my aunt (who was only called so by my brothers and me because she was a close friend of the family) were both fans of horror films. I grew up in the eighties, when the slasher genre was at its height: eight Friday the 13th movies, five Nightmares on Elm Street, four Halloweens. When the Gulf War began, the first one, I was nine years old. The phrase “World War III” was being thrown around by the media, as it tends to be in a world that likes nothing more than to cash in on previous successes with a much-anticipated sequel. I thought the end of the world was coming right to our doorstep in Lacolle, a small Quebec town mostly known for its customs since it shares a border with New York State. I did the only thing that made sense to me at the time: I put my favourite things in a cardboard box in my closet so I could grab it in case we had to leave in a hurry. All I remember putting in it were Legos. In my head, the plan was that my family would escape to the Laurentian Mountains – a mere four-hour drive from Lacolle – where we would live by a lake, humbly eating finger sandwiches and playing cards to entertain ourselves while patiently waiting for the rest of the world to kill each other. My apocalyptic world looked like a bucolic family picnic. Things took a turn for the worse in junior high when I discovered that the cruelty of others was not limited to images of war on television and that the enemy did not always easily identify himself by wearing camo. As a trumpet player, I joined the school’s orchestra, which required staying after school twice a week and taking a later bus. While I was waiting for the bus on the very first evening, a student I didn’t know threatened to beat me up for no apparent reason. The story I told myself was that he was frustrated because he had had to stay for detention. It was the last time I took the later bus. I made up a now long-forgotten excuse for my mother as to why I could no longer take it. From then on, she would come and pick me up twice a week after orchestra practice, a one-hour round-trip. In high school, verbal bullies figured out I was gay before I did because their survival didn’t depend on denial, but also partially because there wasn’t a single guy at my school worth crushing on. They were years of crying myself to sleep, my mother visibly worried by my tears. What she or anyone else didn’t and still doesn’t know is what I would sometimes do when home alone. I would take a sharp knife and lie down with my back against the floor. I would hold the knife above my chest with both hands and swiftly bring it down, stopping it just before it would pierce my skin. Every time I brought down the knife, in that fraction of a second, I would decide whether it would go all the way. No. Not yet. After a few near stabs, I would stand up and put the knife back in the kitchen drawer, until the next time I needed to feel better. Years later, while looking through my high school yearbook, in between typically generic sentences, I came across a singular one handwritten by my drama teacher: “I am no longer worried.” Surely I had read the note before, but it didn’t register until then what it meant. In my last year of high school, my best friend Emilie and I started a new tradition because of Dawson’s Creek: every Friday night, we would rent slashers at the video store and watch them at her house. I envied Emilie because her mother brought her to Montreal to see West Side Story when the show came to the city. A few years ago, I learned through my mother that Emilie had died shortly after giving birth to a daughter, her first child. By then, we had lost touch. I still have the pictures I took of her for a photography class in college. Inspired by slashers, the series has Emilie holding a knife to defend herself against Jason or Freddy or Michael. In one of the pictures, she is lying with her hands resting on her stomach, her eyes closed under a glass coffee table, a make-shift coffin. Once your high school best friend has passed away, there is no longer any reason to believe that you are too young to die. In college, I studied cinema. I still had a soft spot for the first movies I remembered seeing as a child. When came the time to write about slashers, I pondered the source of my attraction to them. To me, they were more exciting than they were scary. I realized that slashers made everything simple: no matter the weight of the world on your shoulders, when a knife-yielding psycho-killer comes after you, you run. In spite of appearances, slashers weren’t about death; they were about life. Every time a person runs, without even thinking, they are saying yes to life, in spite of everything. The movies that most move me are about mortality and, throughout university, I often returned to the theme. I wrote about Agnès Varda’s Cléo de 5 à 7, in which a singer wanders through the streets of Paris while she waits to find out if she has cancer, on at least three different occasions. As Cléo finally faces her inevitable end – cancer or not – she transforms from an object for the gaze of others to a subject with her own life force. She becomes alive. I too wanted to become alive, which meant always being on the verge of death. “Should I kill myself, or have a cup of coffee?” This quote is often attributed to Albert Camus, though there are no records of him ever having written or even said it. All the same, it is a question I am constantly asking myself. So far, I have always chosen the coffee. The subject now seeps into my fiction. In a year when I was in dire need of a better world, I wrote a series of short stories, all highly personal utopias, as utopias always are. Recurring themes included home, food, art, bodies of water, turtles, solitude, love and – yes – death. Despite the brevity of the stories and the low number of characters, five of them still managed to meet their fate, all in the most utopic ways, of course.

I am now simultaneously closer to and further from my death than I was in high school. Today, like every other day, I ask myself if I will finally bring the knife all the way down. No. Not yet.

0 Comments

|

Sylvain Verstricht

has an MA in Film Studies and works in contemporary dance. His fiction has appeared in Headlight Anthology, Cactus Heart, and Birkensnake. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed