|

Le cinéma est le «bizarro» du monde de l’art, le médium commercial. Si «le médium est le message,» le message du cinéma est «je suis dispendieux,» de sorte que c’est souvent l’argent qui y est mis de l’avant (qu’on parle de film à petit ou à gros budget, ou encore de succès ou d’échec au box-office), relayant l’art à l’arrière-plan. Le cinéma se nivelle donc constamment vers le bas à la recherche d’un public potentiel. Ici, je ne parle pas d’élitisme. Ce n’est pas le public qui tue l’art mais bien la possibilité d’un public; c’est-à-dire que l’art commence à mourir du moment que l’artiste croit que s’il fait certains choix plutôt que d’autres, il pourrait ainsi trouver un public. L’art n’est donc que rarement un but au cinéma (s’il en était le but, on choisirait un autre médium, un moins dispendieux*), mais plus souvent qu’autrement un accident. Le cinéma est le «bizarro» parce qu’il est généralement d’une telle médiocrité qu’il crée un univers parallèle où les mauvais films sont ironiquement meilleurs que les bons films. C’est que les films minables sont truffés d’accidents.

Le bon film n’est pas un film artistique mais un film artisanal. Il est un film «bien produit» mais qui ne produit rien. À l’inverse, dans le film «mal fait», le chaos, la vie est partout. Le film minable craque de partout. That’s how the light gets in. «Certains détails pourraient me ‘poindre’,» écrit Roland Barthes. «S’ils ne le font pas, c’est sans doute qu’ils ont été mis là intentionnellement par le photographe.» Dans le film minable, le cinéaste est constamment mis dans la position où il doit filmer l’objet partiel s’il désire l’objet total. Par exemple, s’il veut le dialogue, il n’a pas le choix de filmer le mauvais jeu de l’acteur par le fait même. Du point de vue du spectateur, le dialogue n’est qu’un prétexte. (C’est la banane mise dans le chemin de l’acteur.) Il est une manière d’occuper l’acteur à une tâche (il croit qu’il est en train de jouer un rôle) alors qu’on est plutôt en train de le filmer à faire autre chose (être incapable de jouer un rôle). On utilise cette tactique à outrance dans la télé-réalité, mais aussi dans le documentaire ethnographique Pour la suite du monde, pour lequel les cinéastes ont demandé à la population d’un village de se prêter à la pêche aux marsouins, une excuse pour les filmer, et l’ont ensuite filmée à faire à peu près tout sauf pêcher le marsouin. Le film minable à petit budget relève de l’art primitif. Devant un décor en carton, j’observe des adultes faire semblant, jouer comme des enfants, raconter une chasse aux mammouths fictionnelle. Ceci n’est ironiquement jamais plus évident que dans le film de science-fiction, avec ses green screens et ses décors en papier mâché. Écoutant un épisode de Star Trek, je m’entends penser «Que sont-ils en train de prétendre qu’il se passe?» Le film de science-fiction révèle plus souvent qu’autrement son manque d’imagination. Aussi futuriste peut-il tenter d’être, il n’arrive jamais à transcender la culture de sa propre époque, qu’on parle de mode, de sexisme ou de racisme, par exemple. *À voir comment les artistes se sont accaparés de la vidéo beaucoup plus que du film.

0 Comments

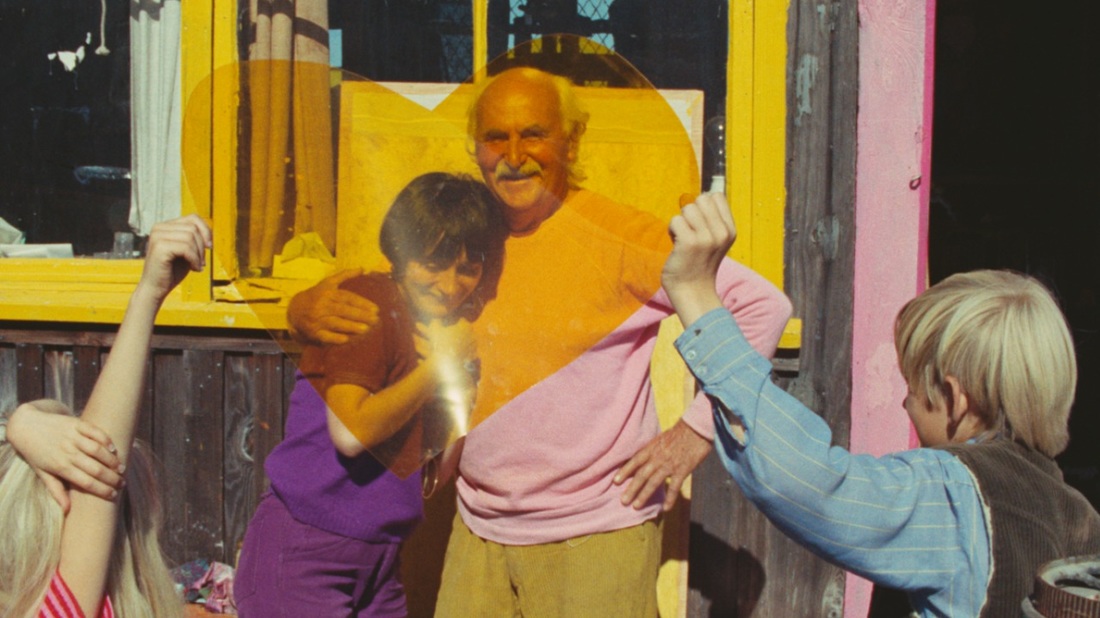

Imitation of Life (1959), directed by Douglas Sirk / written by Eleanore Griffin & Allan Scott Du côté de la côte (1958) & Oncle Yanco (1967), directed & written by Agnès Varda The Things I Cannot Change (1967), directed by Tanya Ballantyne Alucarda (1978), directed by Juan López Moctezuma / written by Alexis Arroyo & Juan López Moctezuma Miele di donna (1981), directed by Gianfranco Angelucci / written by Gianfranco Angelucci & Liliane Betti Charades [aka Felons] (1998), directed by Stephen Eckelberry / written by Richmond Riedel & Karen Black Bedevilled (2010), directed by Cheol-soo Jang / written by Kwang-young Choi The Act of Killing (2012), directed by Joshua Oppenheimer / co-directed by Christine Cynn Stories We Tell (2012), directed by Sarah Polley / written by Sarah Polley & Michael Polley Moonlight (2016), directed by Barry Jenkins / written by Barry Jenkins & Tarell Alvin McCraney

And now, just for fun, let's put all the stills I didn't use that espouse a red, white and blue colour scheme... RATING: 3 colours, i.e. red, white and blue, obviously.

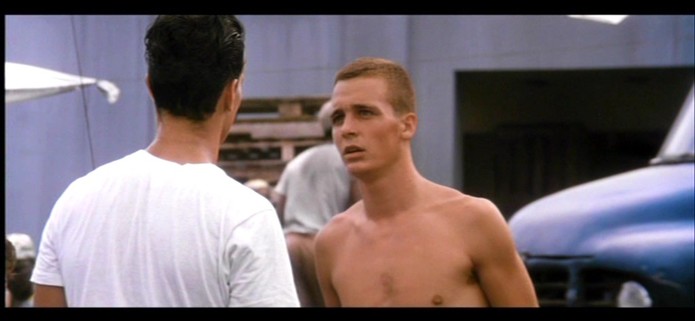

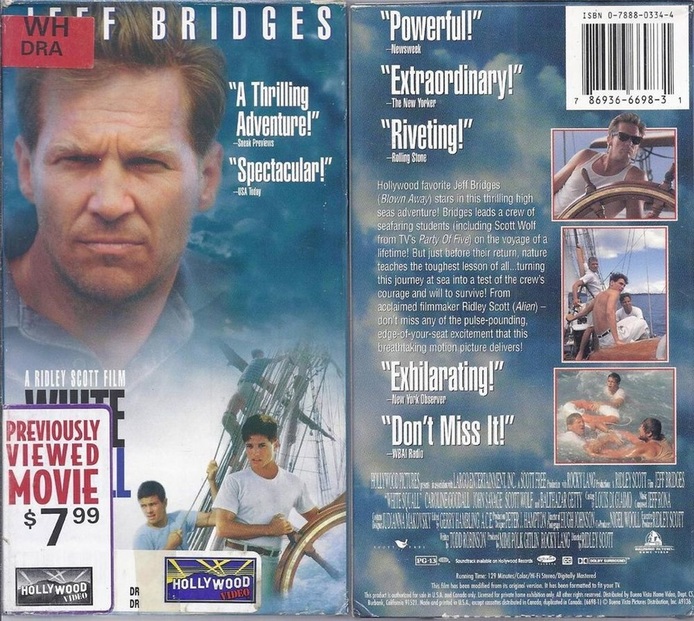

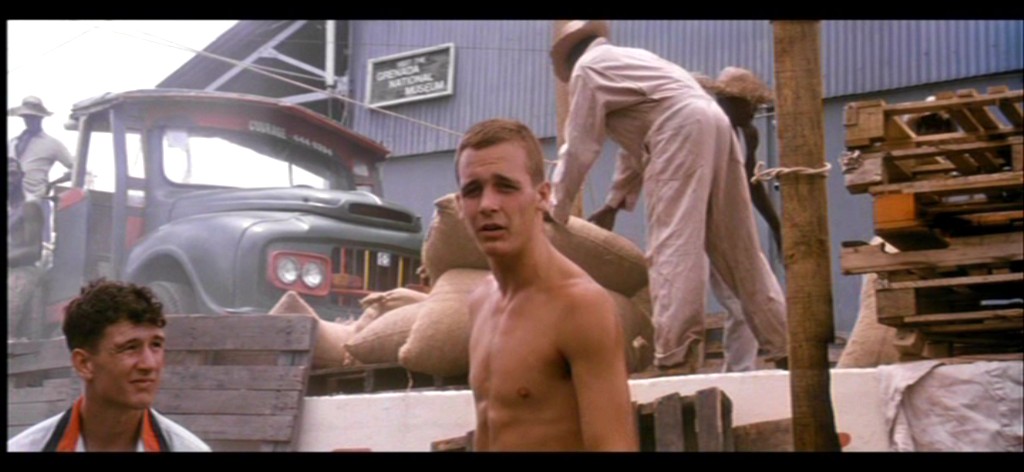

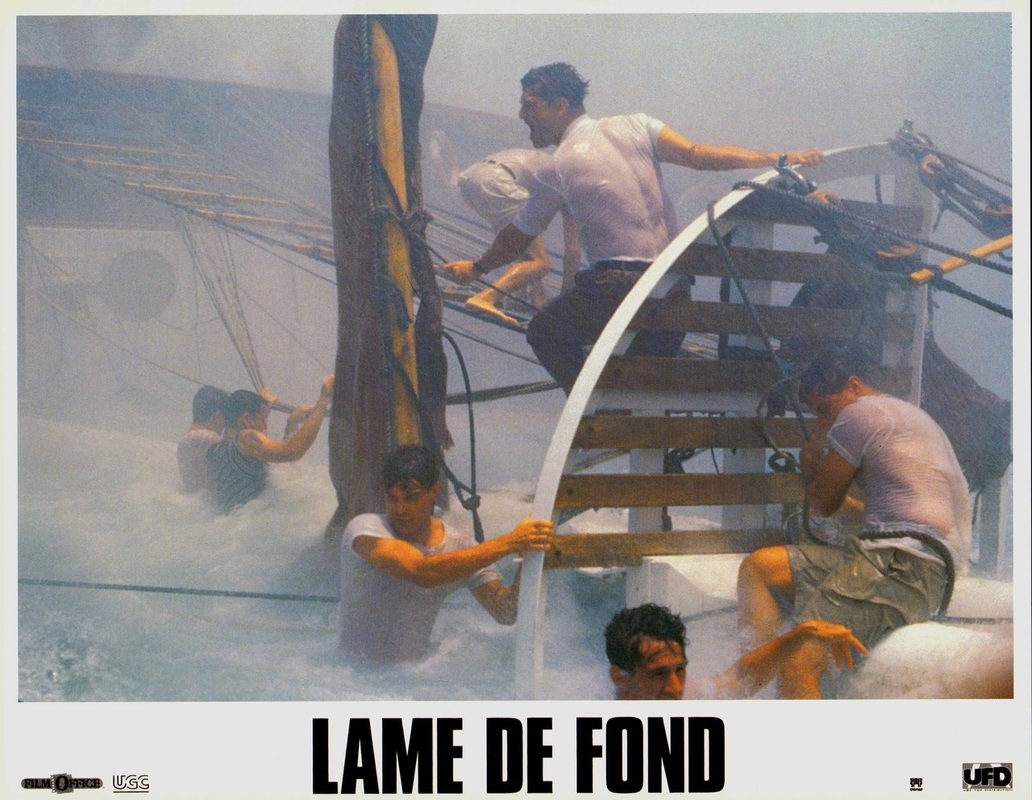

In the 90s, when you grew up in a small town like I did, your options for entertainment were limited: glue sniffing, teen prostitution, and the video store. By the time I was in sixth grade, some of my friends were already dabbling in cocaine. I could be found at the video store. The only legitimate video store in Lacolle (the one that wasn’t just a convenience store with some video shelves in the back) opened on Church Street in what had previously been a flower shop, right in the middle of town, across from the general store and the United Church. I remember the daughters of the general store owners making fun of other kids in elementary school. I also remember them being a lot more demure after their father came out as gay. These are only memories. They might be false. The general store then became a dollar store. Now the building sits empty after the dollar store moved down the street in what used to be a furniture store, one of the largest commercial spaces in town. Of course, the video store didn’t move; it just closed. The building it resided in is a bit of an architectural oddity, a Swiss-chalet-looking top half sitting on a stone bottom broken up by four round windows that give you the impression you’re looking through a fish bowl. I remember walking through the aisles, trying to pick which movie I wanted to get lost in over the weekend based on the jacket. I would often gravitate towards the back, where the horror movies were. When I entered my teens, I would rent movies I was obsessed with (The Mighty Ducks and Speed), play them on the TV and tape them on an audio cassette running through a radio a few feet away. Then I’d listen to the tapes over and over on my yellow Sony Walkman, picturing the movie in my head. I might have enjoyed that even more than watching the actual movies. I didn’t limit myself to blockbusters. Around the same time, I sent my mom to the store with a list of videos I wanted, which included Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Three Colors Trilogy. My mom came back empty-handed. The store owner told her that I was the only one in Lacolle who rented such movies. When you grew up as a queer kid in the country, you took your gay content where you could find it. I would tape as many daytime soap operas as I could and watch them when I would come back from school, buy Soap Opera Digest at the drugstore and cut out pictures of shirtless hunks (I once made a Days of Our Lives collage), and I rented White Squall at the video store. This was all before I came out, even to myself. The VHS tape of White Squall I own comes from that same store – might even be the exact tape I watched the first time – as evidenced by the sticker on it: “WHITE SQUALL ACTION AVENTURE ANGLAIS 0658102.” I recently had to explain to a younger friend of mine that, to rent a movie, you would take a plastic token held by Velcro under the box (red for English movies, black for French ones, to avoid confusion) and present it to the clerk who would go get the videocassette matching the number behind the counter. This was before they figured out a security system that would prevent people from stealing tapes. This system also allowed my teenage self to take tokens for movies that were rated 18+ and hand them over to my mom who would rent the movies for me, oblivious to their content. Given that I grew up on slashers because of her love of horror movies, it is possible that she wouldn’t have cared anyway. As I now read the text on the White Squall jacket, I realize that every sentence – synopsis, tagline, review blurbs – ends with an exclamation point, like in an Archie comic. “The Adventure Of A Lifetime Turns Into The Ultimate Challenge Of Survival!” “Hollywood favorite Jeff Bridges (Blown Away) stars in this thrilling high seas adventure!” “Spectacular!” –USA Today White Squall is not a gay movie, but it is highly homoerotic thanks to its premise: it is about a dozen male teenagers who spend their senior year of high school on a boat instead of on land. The mother of Scott Wolf’s character tells him that his father would have loved to able to do something like this. Who wouldn’t? It’s a teen fantasy. It’s the concept that Breaker High would capitalize on one year later, smartly avoiding the drama that ultimately weighs White Squall down. Having recently watched Dirty Dancing again, I now think of it in the same category as White Squall: slight period pieces that look more like the year they were made than the one they’re pretending to take place in. Dirty Dancing takes place in 1963, but its aesthetic is undeniably that of the year of its release, 1987. White Squall takes place in 1960-61, but it is most definitely from 1996. In the same category, I should maybe add the movie White Squall is most often accused of copying, Dead Poets Society, released in 1989, but pretending to be 1959. Like many such movies, the songs on the soundtrack help to signify and conjure up the time period desired. As a result, we get a lot of black musicians scoring the lives of white characters. The only black people who appear in White Squall are meant to be part of the exotic scenery of the port towns the students visit on their trip around the world. The soundtrack is otherwise; Eddie Cochran is the only white boy in a sea of black musicians: Fats Domino, Tommy McCook, Chubby Checker, and Baba Brooks. (The only contemporary song, Sting’s “Valparaiso”, plays over the end credits like an argument for nostalgia, but I am choosing to ignore it, as the producers of the soundtrack wisely did.) Black people are visually even more absent in Dirty Dancing, but are just as prominent on the soundtrack: The Ronettes, Maurice Williams & the Zodiacs, Merry Clayton, Mickey and Sylvia, and The Five Satins all make apparitions. In this category, we could also add Pleasantville (Robert & Johnny, Larry Williams, Billy Ward and The Dominoes, Etta James, and Miles Davis), which might be the most excusable example since the movie is literally about nostalgic whitewashing.* The absence that was actually enticing to my gay teenage self however was that of women. As critic Roger Ebert noted, in White Squall, “Women play a secondary role (in this case, limited to the transmission and healing of venereal disease).” What we are left with are men pretending to be 16-year-old boys. In reality, most of the actors were around 20 years old. Baby-faced Scott Wolf was 27. In order to pass for teenagers, there is not a single chest hair in sight, though it is possible the actors were already down with shaving before production. In the 90s, body hair wasn’t in. What many critics viewed as one of the film’s faults was specifically what my actual 16-year-old self enjoyed. “[… Director Ridley] Scott has manned his crew with muscular, bronzed young types with keen haircuts, who look as if they hang out in Calvin Klein ads. (When I was 15 or 16, most kids were scrawny and had pimples and cowlicks, and they didn't look a bit like movie stars)”, Ebert pointed out. Entertainment Weekly’s Lisa Schwarzbaum described the film as a rousing salute to “the goodness of young men [who] are allowed to ripen with their shirts off”. The first three quarters of White Squall indeed play like an advertisement for men’s fashion. The first time we see Ryan Phillippe, he is shirtless and glistening. In the 90s, it was in Phillippe’s contract that he needed to be shirtless in every onscreen appearance: The Secrets of Lake Success, I Know What You Did Last Summer, Homegrown, 54, Cruel Intentions. Only The Secrets of Lake Success and Homegrown managed to pass by me. The first thing the men boys do on their first full day on the Albatross is to take their morning shower by jumping into the ocean shirtless, except for Wolf, whose soaked white t-shirt clings to his chest. Bad boy Dean first refuses to jump in like everyone else to assert his individuality, but when First Mate Shay implies that he’s too chicken to jump, Dean climbs higher than anyone else and dives in slow motion because penis. It is no surprise that, later, he is the one flexing before a group of Dutch girls. When the crew pulls on ropes, they also do so shirtless in order to highlight their muscles at work. This environment proves too tantalizing for rich, repressed daddy’s boy Frank Beaumont, who aims a crossbow at a shirtless Shay. Later, he finally boils over and shoots a dolphin with the same crossbow. As Captain Christopher “Skipper” Sheldon, Jeff Bridges is in peak daddy form. “He’s strong, tough, and he won’t take no for an answer,” Wolf writes in his diary, “But he makes you want to please him.” The shirtless shot of Bridges that graces the soundtrack cover is false advertising; he is never actually seen with anything less than a white tank top throughout the movie. Sheldon walks around saying shit that’s meant to be so wise you’d momentarily lose control of your bladder, like “You can’t run from the wind, son.” (Get it? It’s a metaphor. You are the ship and the wind is hardship. Hard ship. Boners. It’s about boners.) Every time one of the boys needs to insult someone, they go straight for the gay. When they discover that Dean is cheating on tests, they corner him. “Where are you going?” Wolf asks him. “To take a piss,” replies Dean. “Oh, really?” inquires Phillippe. “Yeah, you want to come in and shake it for me?” Dean dares him. Later, when Dean is drunk, he slays with, “Look at these guys… They’re homos.” SNAP. When Todd starts peeing fire after having had sex in Grenada, we get to see his bare butt while he shows his flaming penis to the captain’s wife, Dr. Alice Sheldon (Caroline Goodall, unfortunately not related to Jane), though she pulls down his underwear in the next shot (oops, continuity!) to give him a shot of penicillin. After, one of the boys congratulates Todd on getting an STI: “Way to go, Valentino. I never even copped a feel in Grenada.” To which Todd replies, “Yeah, well, your sexual orientation is not my problem.” Apparently, in the 60s, men wanted to get STIs because it proved they weren’t “homos.” Of course, the line between homophobia and homosociality is so porous that, when the boys finally begin to bond, what would have been an insult just a few seconds earlier suddenly becomes a way of showing affection. When they offer to help Dean study, the bad boy asks why they would help him. “We got a hard on for you, pansy,” replies Phillippe, smiling coyly. White Squall is rated PG-13 for “some sexuality” and, unfortunately, “a traumatic shipwreck.” Though the movie received a lukewarm reception from critics, most agreed that it finally picks up in its last act, when the Albatross meets the titular white squall. Personally, that’s when I lose interest. From that point on, nobody has their shirt off and, even though they are soaked, the editing is too fast to allow you to appreciate it; not to mention that homoeroticism tends to be put on the back burner when people are fighting for their lives, even if it’s just a re-enactment. All the drama only makes me wish I could go back to the fantasies of beginnings, to the high school on a boat, the VHS jacket on the shelf, the possibility of escapism. But it’s all nostalgic whitewashing. The Albatross lies at the bottom of the ocean, the video store is closed, and movies rarely work their magic on the jaded adult I’ve become. There is nothing on the other side of the round window. The empty fish bowl speaks: somewhere there is a dead fish. *See Krin Gabbard’s Black Magic: White Hollywood and African American Culture.

RATING: 3 LIVE PUPPIES AND ONE DEAD ONE!!!

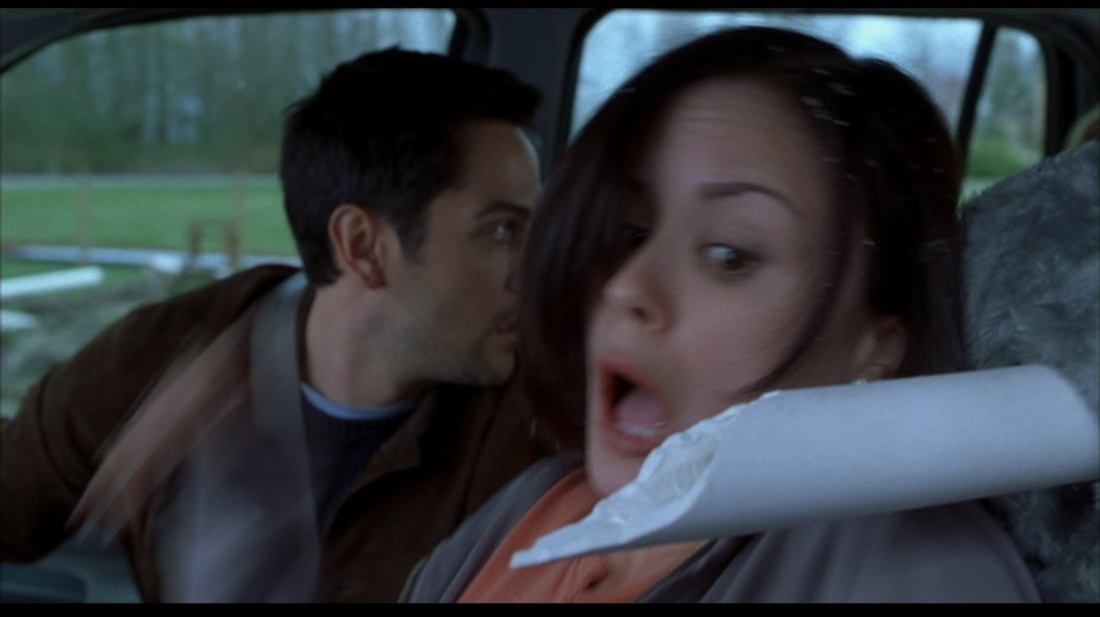

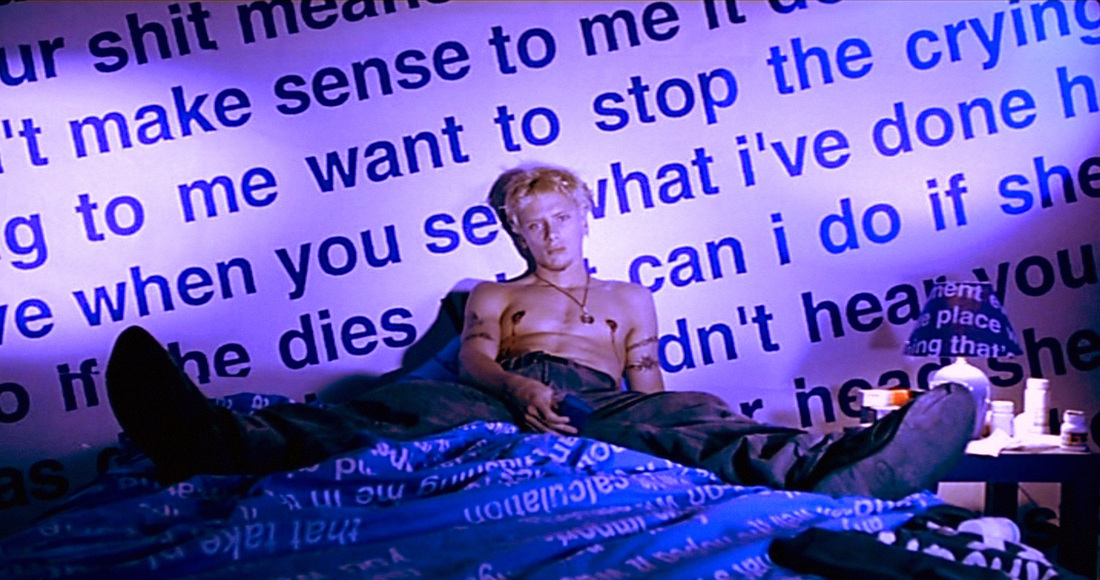

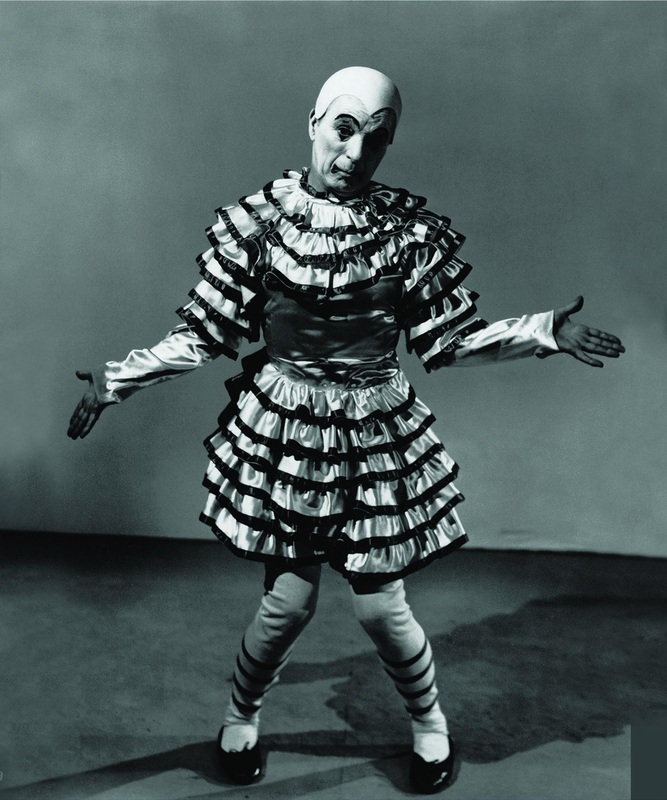

As a critic, I’m well aware that critics are full of shit. And who can blame us? What we do isn’t a science. We are human subjectivities reacting to artistic subjectivities and trying to translate the heat of our emotions into the coldness of words. Good fucking luck. So it’s not surprising that critics sometimes miss the mark. Fortunately, here I am to set the record straight about ten instances where film critics got it wrong… 10. Final Destination 2 (2003) Metacritic: 38 / Rotten Tomatoes: 48 Let’s face it: Final Destination is the best, most fun horror series since Scream. So in about four years, which in movie time is the equivalent of forever. The storyline is more original than most in its genre, presenting death not as a result of evil, but simply as something inevitable. Plus how many series can claim that the sequel is even better than the original, something both the critics and I agree on. 9. The Wicker Man (2006) Metacritic: 36 / Rotten Tomatoes: 15 The original The Wicker Man is a weird British mystery that takes the piss out of English puritanism. I’m not his shrink, so I’m not sure what Neil LaBute’s issue with women is; but, for his American remake, he turns the whole premise around and The Wicker Man becomes some straight male paranoia about being the victim of women. Who knows? Maybe we’re still supposed to laugh at the male protagonist. As such, Nicholas Cage is perfectly cast as an actor overacting. The scene where he highjacks a woman’s bicycle at gunpoint is a piece of anthology. 8. Weekend at Bernie’s (1989) Metacritic: -- / Rotten Tomatoes: 50 Weekend at Bernie’s is a brilliant black comedy about two schmucks who need to carry around the corpse of capitalism in order to stay alive (or so they think). It’s a satirical portrait of the vacuous 80s that plays like slapstick written by Bret Easton Ellis. As a dead body, Terry Kiser gives one of the most underrated comedic performances in cinema. 7. Vanilla Sky (2001) Metacritic: 45 / Rotten Tomatoes: 41 Along with all the other unpopular opinions I’m dishing out here, might as well add one more: I think Vanilla Sky is better than the movie it is based on, Alejandro Amenábar’s Open Your Eyes. It might be one of the few instances where a bigger budget has a positive influence. It gets you from the stunning opening sequence when Tom Cruise runs through an eerily empty Times Square. In the original, after the protagonist’s car accident, Penelope Cruz’s character just comes across as an asshole, whereas in the remake she remains more satisfyingly ambiguous. 6. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992) Metacritic: 28 / Rotten Tomatoes: 61 Some suggest that the Twin Peaks prequel was unpopular because it didn’t have the humour of the TV series, as though that’s relevant. The movie has the benefit of being as unsettling as its subject matter. As a still alive Laura Palmer, Sheryl Lee gives one of the best dramatic performances ever. 5. Drop Dead Gorgeous (1999) Metacritic: 28 / Rotten Tomatoes: 45 This satire of beauty pageants is simply one of the funniest comedies of the 90s. There is a scene where the former winner is so weak from her eating disorder that she has to perform her musical number while being pushed around the stage in a wheelchair. My jaw drops just thinking about it. 4. Showgirls (1995) Metacritic: 16 / Rotten Tomatoes: 17 I suspect that critics dislike Showgirls so profoundly because they don’t know whether to take it seriously or not, when the answer should be both. Showgirls is a candy apple with a rotten core. Another reason why I suspect people hate it is because every single character, including the protagonist, is the worst kind of human garbage. As if that wasn’t bad enough, the filmmakers save the worst fate for the only likeable character. Much like Bret Easton Ellis had with American Psycho, Showgirls draws a line between nihilism and success (the main character’s name is Naomi, i.e. “no me”). Still, it’s hard to see what’s not to like here: Elizabeth Berkley’s giving her all, clearly hoping to be the next Sharon Stone; the hilarious dance numbers look like they’re choreographed by high school girls, but performed by grown-ass naked women; “It must be weird, not having anybody cum on you” is an actual line in the movie; and Kyle MacLachlan has a convulsion-inducing penis. All in all, Showgirls is a compelling allegory of Hollywood/capitalism/America/take your pick. 3. A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge (1985) Metacritic: -- / Rotten Tomatoes: 42 The sequel to A Nightmare on Elm Street is widely regarded as one of the worst in the series; yet it’s the kind of movie that is utterly fascinating to watch. It is simultaneously the most homophobic and the gayest mainstream horror movie of all time. Freddy becomes a symbol for the protagonist’s latent homosexuality and our hero defeats him by kissing a girl. No shit. It’s like watching a horror flick written by a born again Christian. Plus it’s refreshing to see shirtless men in a slasher instead of women for once. 2. The Rules of Attraction (2002) Metacritic: 50 / Rotten Tomatoes: 43 Out of all the movies based on his novels, Bret Easton Ellis considers The Rules of Attraction to be the best. Yes, even better than American Psycho. From its compelling opening sequence that plays in reverse, The Rules of Attraction avoids the usual downfalls of adaptations and becomes downright cinematic. Screenwriter/director Roger Avary keeps the characters’ bleak sense that nothing they do matters, yet manages to derive some unexpected meaning from their antics. That’s no easy feat when you consider the author of the source material. 1. Nowhere (1997) Metacritic: -- / Rotten Tomatoes: 27 Out of all his movies, Gregg Araki’s Nowhere has the lowest rating on Rotten Tomatoes. Yet I personally think it’s his best. Not surprisingly, critics prefer what is probably his most conventional one, Mysterious Skin (though it's great too). However, Nowhere is the quintessential portrait of the 90s, with a generation that thinks the end of the world is imminent and ineffectively deals with it by fucking. Despite being ridiculously over the top, its ending is one of the most depressing of any movie out there. Are there any movies trashed by critics that you think are actually good? RATING: 3 metaphorical deaths staged by Chaplin himself

I stopped going to the movies around the same time I finished my master in film studies. It’s probably because 1) I’m poor and 2) I’d rather spend what little money I have on live performance. I saw fewer movies released in 2013 than I have from any other year since 1951. But I still saw quite a few on video and here are the ones that had the biggest impact on me. Life in a Day, Kevin Macdonald (2011) Carnival of Souls, Herk Harvey (1962) The Trip, Roger Corman (1967) Cruising, William Friedkin (1980) Commando, Mark L. Lester (1985) Samsara, Ron Fricke (2011) Children of the Damned, Anton M. Leader (1963) Village of the Damned, Wolf Rilla (1960) Drive, Nicolas Winding Refn (2011) Reality Bites, Ben Stiller (1994) Weekend, Andrew Haigh (2011) Spring Breakers, Harmony Korine (2012)  A large checkerboard, a trivial human figure. The beam of light from a projector appears in front of the viewer instead of just behind. The screen becomes a mirror, reminding the viewer: this is not reality; it’s just a movie. The projector lights up the title, Inland Empire, by David Lynch. At the beginning of Mélanie Demers’s Goodbye, dancer Jacques Poulin-Denis opens with a typical Demers move, a series of statements paradoxical in their juxtaposition: “This is not the show,” he tells us. “Not a flat screen, not reality.” The question that always emerges with Demers is: then what is it? One should never readily believe what the performers are saying. Of course, when Poulin-Denis is claiming, “This is not the show,” he is reminding us of the opposite: this is a show. But does it even matter one way or another? Extreme close-up of a needle on a vinyl record. To say that it’s just music is to undermine the kind of emotional manipulation that art is involved in.  The Black Lodge. Even the electric guitar riffs in Goodbye are reminiscent of Lynch, most particularly Angelo Badalamenti’s score for the Twin Peaks series. That’s not to mention the floor, a black-and-white checkerboard of inhuman proportions that dramatizes the space and makes the dancers look trivial, like mere chess pieces. The Black Lodge. A woman watches television, though on it there is nothing but static. Soon, however, the TV image gives way to animated rabbits in their apartment. It could all be in her head. Se faire son cinéma. Do we need to believe that Brianna Lombardo and Poulin-Denis are really a couple to be affected by their dance? Of course not. The moment they interact, the moment they touch, the moment they move together, they enter into a relationship, their actions have consequences. We don’t need to believe that Grace Zabriskie is not Grace Zabriskie. She just needs to walk in, creepy as fuck. If you don’t feel anything, it’s because you’re taking Zabriskie for granted; as real. Suspension of disbelief is a myth. The true power of cinema lies in complete and utter disbelief. Demers is not even trying to pretend. When a performer needs to have tears running down their face, they use eye drops. The microphones they hold are fake, aluminum paper balls on black sticks; the knife, an aluminum paper blade. No one will get hurt. At least not because of objects. No matter how much I hate metaphors, I must recognize that most blades are metaphorical. Artistic ones, always. When Laura Dern gets fake stabbed, she runs down Hollywood Boulevard before falling in front of one of the stars from the Walk of Fame. Lynch will not allow you to believe any of it is real. It doesn’t matter. If you are only affected by things that are real, you’re not human. When Poulin-Denis looks up at the audience while Demers is sucking on his nipple, his reaction is to say, “No, no… It’s not what you think. This is not the show.” The statement is of course hilariously ironic. Demers knows that such a strong image is bound to have an effect on the audience. Would it have any less of an effect if we were to take it in as reality? Of course not. Quite the contrary.  Actors playing actors. Whenever Dern and Justin Theroux have a scene together, we never quite know whether they are the actors they are portraying in the movie or the characters the actors are portraying in the movie in the movie. At one point, Dern screams out, “Damn! This sounds like dialogue from our script!” That’s because, of course, it is. First and foremost, and if nothing else, every movie is about people making a movie. Another typical Demers move: when Poulin-Denis is wiping the water off the floor, he is of course doing so for the dancers’ safety; but, by virtue of being performed onstage, the action is also necessarily dramatic. An everyday gesture becomes an artistic one. “Il y a de l’éclairage, des costumes…” he says, laying out the reasons why we might be inclined to think that this is a show. As if those things didn’t exist outside of the theatre… “Is this our set?” Dern asks. She means in the movie in the movie. However, the set only ends up getting used in the movie. Every space is one location scout away from becoming a set. Later, when Poulin-Denis is the one sucking on Lombardo’s nipple, Chi Long shouts, “This is it! This is the show!” Yet the gesture is essentially the same as before. If anything, the gender reversal and repetition (and therefore lack of surprise) have made it more socially acceptable, less dramatic. It’s always been the show, even before Goodbye ever started. The needle on the record, the music, the emotional manipulation... The viewer cries. She cries because she relates with the character Dern is playing. (What in The Wars Timothy Findley beautifully refers to as “shouts of recognition.”) They encounter each other and kiss in the television. Art as a meeting ground, as the space where artist and audience come into contact, where the line between the artistic and the everyday gets blurred. Goodbye. No, really, goodbye. Poulin-Denis keeps telling the audience the show is over, in so many different ways that it becomes comical, yet the audience doesn’t leave. This is still the show. When does it really end? What are the cues? When the stage lights fade out, when the house lights come on, when the performers take a bow, when we clap, when we leave the theatre, when we finally stop thinking about the show… Some shows never end. And, even when shows do end, what awaits us outside the theatre? More metaphorical blades. Theatre.

usine-c.com maydaydanse.ca davidlynch.com |

Sylvain Verstricht

has an MA in Film Studies and works in contemporary dance. His fiction has appeared in Headlight Anthology, Cactus Heart, and Birkensnake. Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed