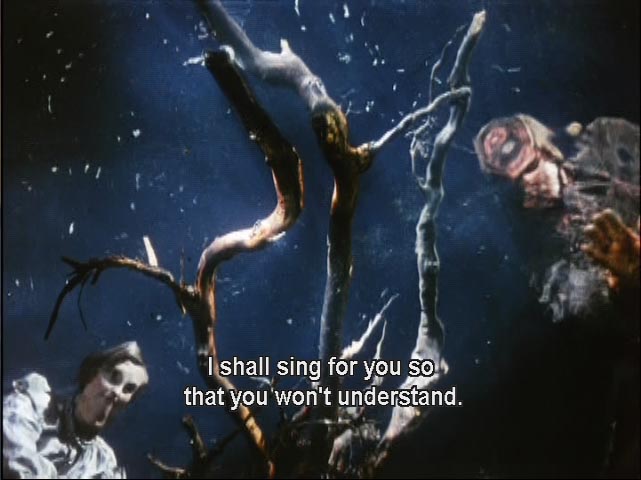

Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors or The Nutcracker? Near the end of Sergei Parajanov’s Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, there is a 360-degree non-stop pan of characters in a circle around the camera that builds to such speed that people lose their edge and bleed externally as objects dissolve into spirographs of colours. This shot is representative of Shadows as a whole, a film that constantly points to everything around it, becoming a kaleidoscope of everything other than itself. The film pegs itself as a “poetic drama”, a term surely used to warn any audience member against the hopes of a straightforward narrative. Shadows can get away with its “Look at me, I’m artsy!” claims, mainly because it is indeed so boldly artistic that, despite being released in 1964, it looks like it’s from the 80s. If art begins at the level of excess – as in beyond the everyday – then the 80s might just be the most artistic decade of the century. Despite what its critics might have had to say about the infamous decade in its wake, its vacuousness – that is to say its disconnect from the everyday – and its revelling in artifice are the qualities that are now ensuring our enduring fascination with it. Of course, part of the appeal is also that we have vastly been ignoring that entertainment creates itself by exceeding its own excess, so that any blockbuster currently in theatres makes a movie like E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982) look downright quaint. So when Parajanov offers a point-of-view shot from a falling tree – after all, vacuousness ensures that a tree isn’t any more lifeless than a human being – it’s hard not to think of Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead (1981) and its own malevolent tree. It too was given a P.O.V., as though trees had more consciousness and agency than human beings. In fact, the acting in Shadows is often just as wooden as the trees, which only contributes to its artifice. If good acting is a craft, bad acting is an art. Soon, however, the film settles on a 70s aesthetic of faded images, both in terms of focus and colour. It looks like my European heritage playing on Télé-Québec, which might explain the costume and art direction similarities with Astérix & Obélix. Even moustaches become works of art, sculpted into perfect shapes, which might contribute in making the men look like figures on playing cards. Ivan, the main character, is the Jack of Hearts or Diamonds. Definitely a red suit. The editing dares to be non-chronological, beyond the demands of storytelling. Like memory, it jumps from year to year, from moment to moment. Each image defies positioning, neither before nor after, never present. The older actor eerily resembles the younger one playing the same character, unlike most movies for which we must suspend our disbelief and pretend a character grew up to look completely different, yet believe they are indeed one and the same person simply because they both happen to have blond hair. Watching a movie that takes place in nineteenth-century Ukraine can leave one perplexed with questions such as “Why does the characters’ house look better than mine?” or “Why are these people sharper dressers than me given that there’s not a single fashion magazine in sight?” One must find comfort in knowing that, at least, if it were to rain, one’s floor wouldn’t turn to mud; or that the characters look more uncomfortable in their oppressive outfits. And the spirograph continues. Surely, Ridley Scott must have been influenced by Parajanov’s misty forest shots for The Duellists (1977). George Lucas must too have been influenced by the look of Shadows for Star Wars (1977), in his case when it comes to the cloaks some of the characters wear. In turn, this might explain the similarities with Masters of the Universe (1983-1985), as the toys were produced after Mattel CEO Ray Wagner had rejected the offer to produce action figures based on Star Wars back in 1976, clearly not anticipating the wild success the movie franchise would obtain. As for the influences on Shadows, we could speak of Tarkovskian shots of reflections in water, or the series of fake still images for which the female protagonist remains immobile, much like Tippi Hedren in Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963). The main difference with the latter is that, while the shots of Hedren were of her reacting to an explosive action, in Shadows the woman is not reacting to anything. Like everything else about Shadows, it’s this nothingness that makes it extra artsy.

3 Comments

|

Sylvain Verstricht

has an MA in Film Studies and works in contemporary dance. His fiction has appeared in Headlight Anthology, Cactus Heart, and Birkensnake. Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed