|

I stopped going to the movies around the same time I finished my master in film studies. It’s probably because 1) I’m poor and 2) I’d rather spend what little money I have on live performance. I saw fewer movies released in 2013 than I have from any other year since 1951. But I still saw quite a few on video and here are the ones that had the biggest impact on me. Life in a Day, Kevin Macdonald (2011) Carnival of Souls, Herk Harvey (1962) The Trip, Roger Corman (1967) Cruising, William Friedkin (1980) Commando, Mark L. Lester (1985) Samsara, Ron Fricke (2011) Children of the Damned, Anton M. Leader (1963) Village of the Damned, Wolf Rilla (1960) Drive, Nicolas Winding Refn (2011) Reality Bites, Ben Stiller (1994) Weekend, Andrew Haigh (2011) Spring Breakers, Harmony Korine (2012)

0 Comments

A large checkerboard, a trivial human figure. The beam of light from a projector appears in front of the viewer instead of just behind. The screen becomes a mirror, reminding the viewer: this is not reality; it’s just a movie. The projector lights up the title, Inland Empire, by David Lynch. At the beginning of Mélanie Demers’s Goodbye, dancer Jacques Poulin-Denis opens with a typical Demers move, a series of statements paradoxical in their juxtaposition: “This is not the show,” he tells us. “Not a flat screen, not reality.” The question that always emerges with Demers is: then what is it? One should never readily believe what the performers are saying. Of course, when Poulin-Denis is claiming, “This is not the show,” he is reminding us of the opposite: this is a show. But does it even matter one way or another? Extreme close-up of a needle on a vinyl record. To say that it’s just music is to undermine the kind of emotional manipulation that art is involved in.  The Black Lodge. Even the electric guitar riffs in Goodbye are reminiscent of Lynch, most particularly Angelo Badalamenti’s score for the Twin Peaks series. That’s not to mention the floor, a black-and-white checkerboard of inhuman proportions that dramatizes the space and makes the dancers look trivial, like mere chess pieces. The Black Lodge. A woman watches television, though on it there is nothing but static. Soon, however, the TV image gives way to animated rabbits in their apartment. It could all be in her head. Se faire son cinéma. Do we need to believe that Brianna Lombardo and Poulin-Denis are really a couple to be affected by their dance? Of course not. The moment they interact, the moment they touch, the moment they move together, they enter into a relationship, their actions have consequences. We don’t need to believe that Grace Zabriskie is not Grace Zabriskie. She just needs to walk in, creepy as fuck. If you don’t feel anything, it’s because you’re taking Zabriskie for granted; as real. Suspension of disbelief is a myth. The true power of cinema lies in complete and utter disbelief. Demers is not even trying to pretend. When a performer needs to have tears running down their face, they use eye drops. The microphones they hold are fake, aluminum paper balls on black sticks; the knife, an aluminum paper blade. No one will get hurt. At least not because of objects. No matter how much I hate metaphors, I must recognize that most blades are metaphorical. Artistic ones, always. When Laura Dern gets fake stabbed, she runs down Hollywood Boulevard before falling in front of one of the stars from the Walk of Fame. Lynch will not allow you to believe any of it is real. It doesn’t matter. If you are only affected by things that are real, you’re not human. When Poulin-Denis looks up at the audience while Demers is sucking on his nipple, his reaction is to say, “No, no… It’s not what you think. This is not the show.” The statement is of course hilariously ironic. Demers knows that such a strong image is bound to have an effect on the audience. Would it have any less of an effect if we were to take it in as reality? Of course not. Quite the contrary.  Actors playing actors. Whenever Dern and Justin Theroux have a scene together, we never quite know whether they are the actors they are portraying in the movie or the characters the actors are portraying in the movie in the movie. At one point, Dern screams out, “Damn! This sounds like dialogue from our script!” That’s because, of course, it is. First and foremost, and if nothing else, every movie is about people making a movie. Another typical Demers move: when Poulin-Denis is wiping the water off the floor, he is of course doing so for the dancers’ safety; but, by virtue of being performed onstage, the action is also necessarily dramatic. An everyday gesture becomes an artistic one. “Il y a de l’éclairage, des costumes…” he says, laying out the reasons why we might be inclined to think that this is a show. As if those things didn’t exist outside of the theatre… “Is this our set?” Dern asks. She means in the movie in the movie. However, the set only ends up getting used in the movie. Every space is one location scout away from becoming a set. Later, when Poulin-Denis is the one sucking on Lombardo’s nipple, Chi Long shouts, “This is it! This is the show!” Yet the gesture is essentially the same as before. If anything, the gender reversal and repetition (and therefore lack of surprise) have made it more socially acceptable, less dramatic. It’s always been the show, even before Goodbye ever started. The needle on the record, the music, the emotional manipulation... The viewer cries. She cries because she relates with the character Dern is playing. (What in The Wars Timothy Findley beautifully refers to as “shouts of recognition.”) They encounter each other and kiss in the television. Art as a meeting ground, as the space where artist and audience come into contact, where the line between the artistic and the everyday gets blurred. Goodbye. No, really, goodbye. Poulin-Denis keeps telling the audience the show is over, in so many different ways that it becomes comical, yet the audience doesn’t leave. This is still the show. When does it really end? What are the cues? When the stage lights fade out, when the house lights come on, when the performers take a bow, when we clap, when we leave the theatre, when we finally stop thinking about the show… Some shows never end. And, even when shows do end, what awaits us outside the theatre? More metaphorical blades. Theatre.

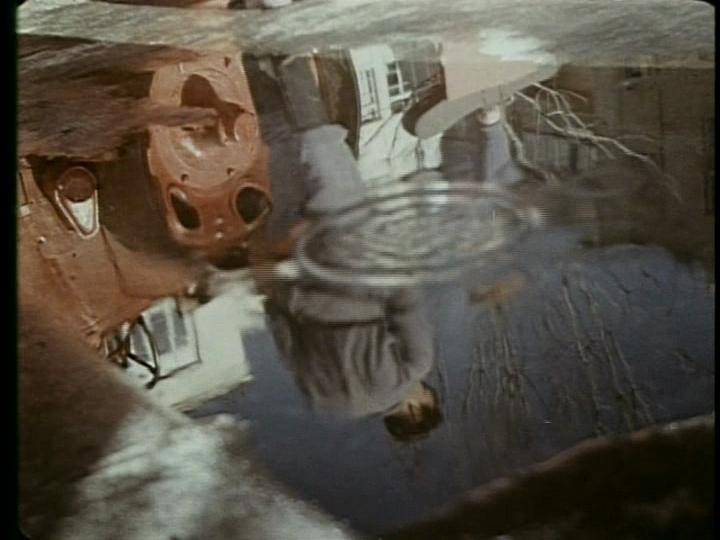

usine-c.com maydaydanse.ca davidlynch.com  Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors or The Nutcracker? Near the end of Sergei Parajanov’s Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, there is a 360-degree non-stop pan of characters in a circle around the camera that builds to such speed that people lose their edge and bleed externally as objects dissolve into spirographs of colours. This shot is representative of Shadows as a whole, a film that constantly points to everything around it, becoming a kaleidoscope of everything other than itself. The film pegs itself as a “poetic drama”, a term surely used to warn any audience member against the hopes of a straightforward narrative. Shadows can get away with its “Look at me, I’m artsy!” claims, mainly because it is indeed so boldly artistic that, despite being released in 1964, it looks like it’s from the 80s. If art begins at the level of excess – as in beyond the everyday – then the 80s might just be the most artistic decade of the century. Despite what its critics might have had to say about the infamous decade in its wake, its vacuousness – that is to say its disconnect from the everyday – and its revelling in artifice are the qualities that are now ensuring our enduring fascination with it. Of course, part of the appeal is also that we have vastly been ignoring that entertainment creates itself by exceeding its own excess, so that any blockbuster currently in theatres makes a movie like E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982) look downright quaint. So when Parajanov offers a point-of-view shot from a falling tree – after all, vacuousness ensures that a tree isn’t any more lifeless than a human being – it’s hard not to think of Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead (1981) and its own malevolent tree. It too was given a P.O.V., as though trees had more consciousness and agency than human beings. In fact, the acting in Shadows is often just as wooden as the trees, which only contributes to its artifice. If good acting is a craft, bad acting is an art. Soon, however, the film settles on a 70s aesthetic of faded images, both in terms of focus and colour. It looks like my European heritage playing on Télé-Québec, which might explain the costume and art direction similarities with Astérix & Obélix. Even moustaches become works of art, sculpted into perfect shapes, which might contribute in making the men look like figures on playing cards. Ivan, the main character, is the Jack of Hearts or Diamonds. Definitely a red suit. The editing dares to be non-chronological, beyond the demands of storytelling. Like memory, it jumps from year to year, from moment to moment. Each image defies positioning, neither before nor after, never present. The older actor eerily resembles the younger one playing the same character, unlike most movies for which we must suspend our disbelief and pretend a character grew up to look completely different, yet believe they are indeed one and the same person simply because they both happen to have blond hair. Watching a movie that takes place in nineteenth-century Ukraine can leave one perplexed with questions such as “Why does the characters’ house look better than mine?” or “Why are these people sharper dressers than me given that there’s not a single fashion magazine in sight?” One must find comfort in knowing that, at least, if it were to rain, one’s floor wouldn’t turn to mud; or that the characters look more uncomfortable in their oppressive outfits. And the spirograph continues. Surely, Ridley Scott must have been influenced by Parajanov’s misty forest shots for The Duellists (1977). George Lucas must too have been influenced by the look of Shadows for Star Wars (1977), in his case when it comes to the cloaks some of the characters wear. In turn, this might explain the similarities with Masters of the Universe (1983-1985), as the toys were produced after Mattel CEO Ray Wagner had rejected the offer to produce action figures based on Star Wars back in 1976, clearly not anticipating the wild success the movie franchise would obtain. As for the influences on Shadows, we could speak of Tarkovskian shots of reflections in water, or the series of fake still images for which the female protagonist remains immobile, much like Tippi Hedren in Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963). The main difference with the latter is that, while the shots of Hedren were of her reacting to an explosive action, in Shadows the woman is not reacting to anything. Like everything else about Shadows, it’s this nothingness that makes it extra artsy.

|

Sylvain Verstricht

has an MA in Film Studies and works in contemporary dance. His fiction has appeared in Headlight Anthology, Cactus Heart, and Birkensnake. Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed